This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1953 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

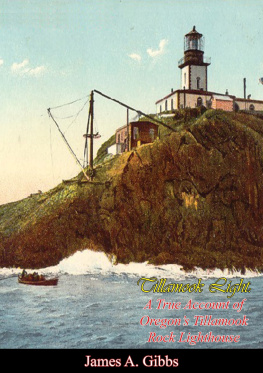

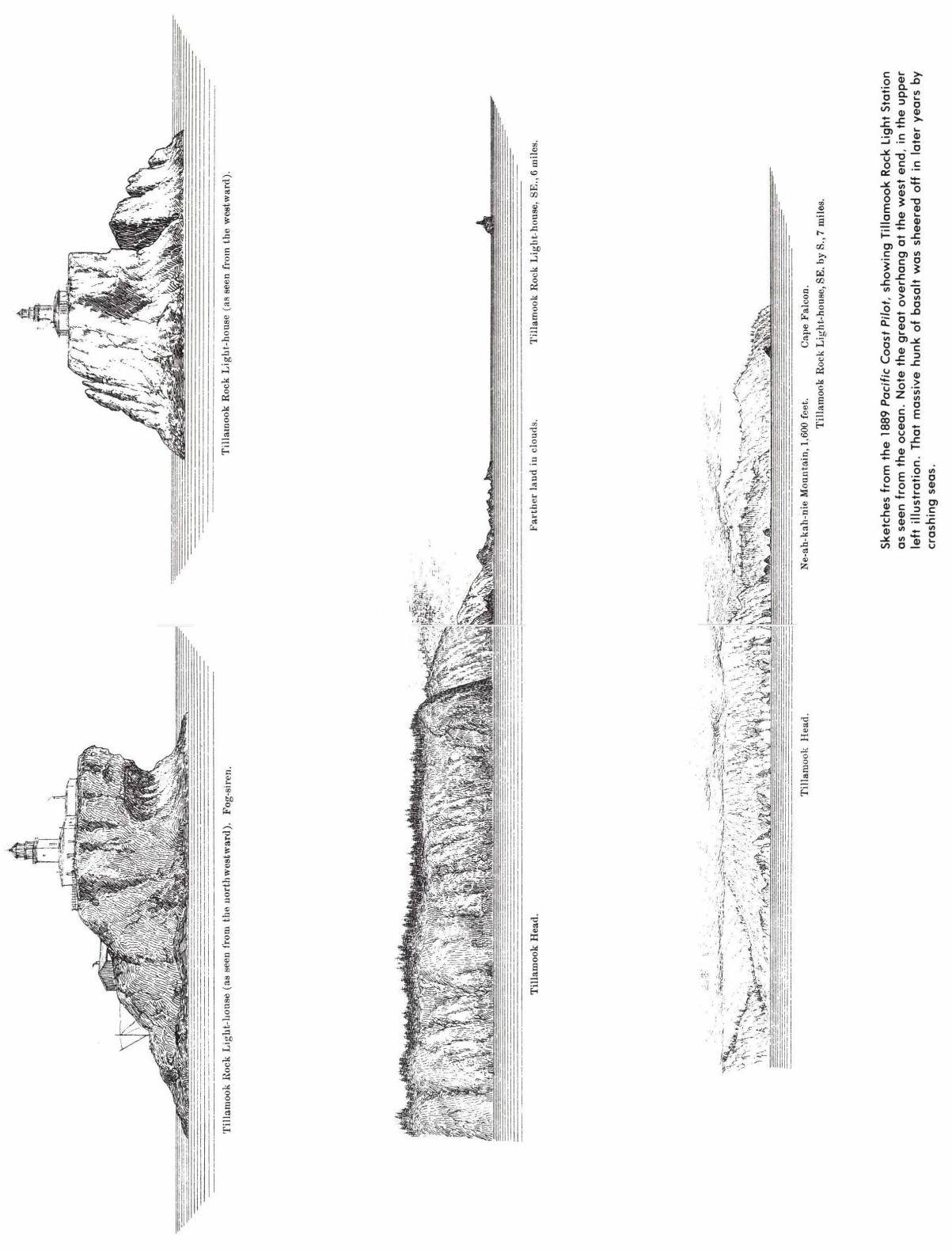

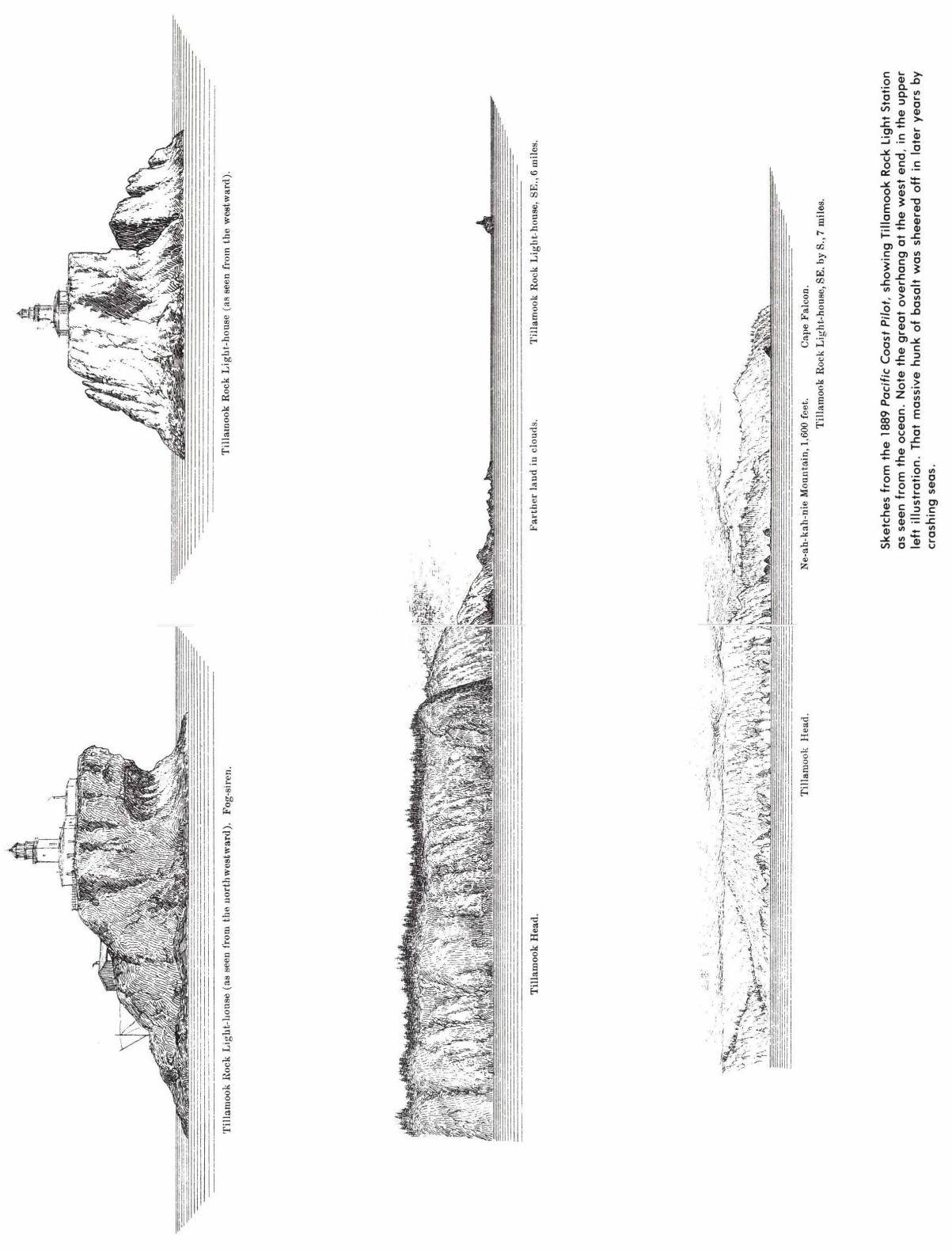

TILLAMOOK LIGHT:

A TRUE NARRATIVE OF OREGON'S TILLAMOOK ROCK LIGHTHOUSE

BY

JAMES A. GIBBS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

To the memory of my mother

who put up with a maverick son

FOREWORD

For a century, lonely Tillamook Rock and its lighthouse have been a sentimental part of Oregon. A warning beacon to thousands of vessels skirting the coast or bound for the Columbia River bar, it was known to mariners the world over, and adopted by the resort towns of Seaside and Cannon Beach. Standing ever vigilant, manned by faithful attendants, it warned ships away from the surrounding marine graveyard for eight decades. Then in 1957, its light went out forever.

One of Americas three most famousand at the same time infamouswave-swept offshore lighthouses, Tillamook Light was, on completion in 1881, considered a great engineering triumph, but a structure that was to take an unmerciful beating from the elements in the years that followed.

Tillamook Light tells its colorful story, from oil lamps to electricity, from important navigational aid to dilapidation. This is an authentic personal account using actual names and situations. The first Tillamook Light was published in 1953, but because the main characters were still living, the text was fictionalized.

The aids to navigation mission of the U.S. Coast Guard has a history dating back to the building and illumination of the first American lighthouse on Little Brewster Island in Boston Harbor in 1716. At first, because of the indifference of England, local or Colonial governments had to shoulder the responsibility of making the waters safe for mariners. Following independence, the newly created Congress of the United States formed the Lighthouse Establishment as an administrative unit of the Federal Government, on August 7, 1789. Before being transferred to and consolidated with the U.S. Coast Guard, July 1, 1939, it was under the Lighthouse Board or the U.S. Lighthouse Service and later the Bureau of Lighthouses, from 1852 to 1939. During the active years of Tillamook Rock Light Station, the lighthouse served under the latter branches.

Tillamook Rock Light stands as a symbol of mans relentless fight against the cruelties of the sea. The monolith on which it stands still resists the buffetings of the Pacific as it has for countless centuries. Great seas still break over it and the winds continue their assault with unabated fury.

No story of a lighthouse would be complete without relating the problems and heartbreaking difficulties that beset the builders, or those who manned the station, particularly at such a harsh location. It has been a battle of men against the sea, epics of daring and enduranceand an ever-present touch of humor.

The most magnificent of lighthouses was perhaps built some 2,200 years ago, the lofty Pharos of Alexandria, near the mouth of the Nile, but to this writer that classification belonged to Tillamook Rock Lighthouse during its active years.

From its inception, Tillamook Light had defied all dire predictions of its impending disaster. Originally labeled as the hoodoo light, in many minds it was but a matter of time until it would be tumbled into the sea, as was the first lighthouse on Minots Ledge. Gloomy prophets predicted that no human beings would be willing or able to endure the hardships of such a station. Yet, men were found who did endure the peculiarities, the dangers, the privation and the loneliness. The light kept shining and the foghorn blasting until the day Uncle Sam decided that the antique sentinel was no longer essential to safe navigation.

No one can say how many ships from the nations of the world were guided by Tillamook Rocks faithful beams of light during its heyday, but it was one of many navigational signposts marking Americas principal sea-roads. Ever since man took to the ocean to earn his daily bread, he has depended on lights along the shore. For centuries he sailed the seven seas when lights were few. He steered his fragile ships, guided by omens, superstitions and some knowledge of astronomy. Later came the cross staff and the astrolabe, crude instruments that enabled him to get an angle on the sun to estimate his approximate position. Next came the quadrant, sextant, compass and the chronometer.

As knowledge of navigation increased, there were crude logs to measure a vessels speed. Then, through the use of mathematics and more advanced astronomy, celestial navigation came into its own. A fantastic breakthrough occurred in the early 1920s when radio was introduced to navigators. In sequence, radar, sonar, radio beacons and Loran revolutionized navigation, and with the advent of automation and computerization, the traditional old lighthouse that had held sway from the time man first hoisted a sail, became a secondary necessity to men of the sea.

Though the keepers are gone and many lighthouses retired, lights and horns still function, and the fear of the dangerous outcrops along the shore still remains. From the earliest seafarers down to the masters of the mammoth supertankers of our day, one common fear remainsoddly enough, the fear of land. In the wind-ship era, many rough, tough skippers, totally relaxed at sea, became nervous tyrants when faced with the obsession of coastal shipwreck. Some skippers are known to have locked themselves in their cabins on making a landfall, and, even today, almost every shipmaster will confess to a certain apprehension on nearing land after crossing an ocean.

The so-called blue-water men in olden times always downgraded the coastwise navigators, especially along the Pacific coast. Actually it was the latter who not only faced the greatest danger but were often the best at their trade. Constantly they dodged other ships in the heavily traveled steamer lanes, hopped from one doghole to the next, darted in and out of tight bar entrances, and battled pea-soup fogs and white-maned seas, which were often pockmarked with reefs and rocks waiting to tear apart any vessel unfortunate enough to get a mile off course.

It is little wonder that coast mariners had a much greater appreciation of lights along the shorethe least of which was Tillamook Light. As for the landlubbers of Oregon, the rock was a part of them too. Nearly all of the material used in the construction of the lighthouse came from Oregon sources. Hard black Clackamas stone, 8,500 cubic feet of it, was barged to Astoria and loaded aboard the U.S. revenue cutter Thomas Corwin for transportation to the rock. The 96,600 bricks used in the project are also believed to have been kilned somewhere in the state. Katherine ONeill, of Portland, recalls that her grandfather supplied the iron and steel. The building of the lighthouseunder the direction of Col. G. L. Gillespie, army engineer who was also on the Lighthouse Service Boardwas ranked in Washington, D.C. headquarters as a notable achievement. Colonel Gillespie later became Chief of Army Engineers.

Next page