Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Eugene H. Ware

All rights reserved

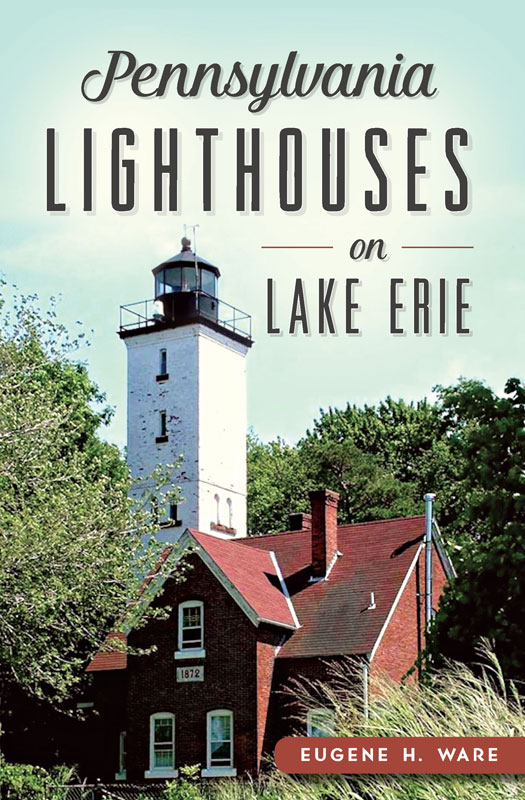

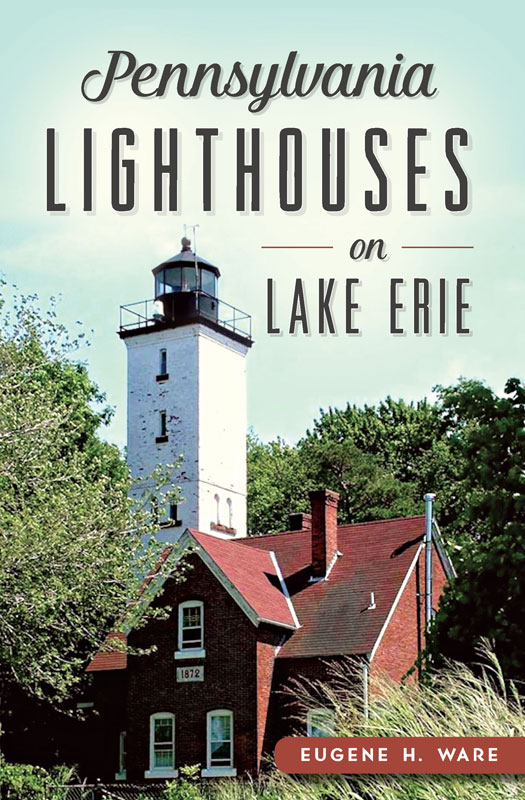

Front cover: Presque Isle Light Station. Authors collection.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.603.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945696

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.874.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The first known light beacon in the world, the Pharos of Alexandria, was located on an island at the head of the harbor to the port of Alexandria, Egypt. Pharos was originally lit sometime in 250 BC, after more than twenty years of construction. Greek architect Sostratus of Gnidus was in charge of designing and building this massive structure, the base and first two floors of which measured 98 feet square. A central light tower rose an additional 367 feet. Alexander the Great built the structure in the city he named for himself, and it was said to have cost over 267 tons of silver.

The Pharos was in full-time use until AD 641, when Islamic warriors conquered Alexandria and caused serious damage to the light and building during their long siege. That means the building, at that point, had been in service for an unimaginable ten centuries. While it was not in use the entire time, it actually survived for an additional five hundred years until it was finally destroyed by a series of earthquakes in the fourteenth century. Today, Pharos is recognized as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Before Pharos, the first lighting systems were designed to help mariners by providing early warning of submerged rocks, reefs, cliffs and sandbars where ships could run aground. They were also used to help alert ships of other coastal hazards. Most were very primitive methods, such as fires on the cliffs or beaches. Two huge problems with these fires were the vast supply of wood that was always necessary and the fact that the fires had to be constantly watched and supervised. It was not long before the builders of these fire-based lights realized that by elevating these fires, they could be seen farther out at sea. Thus began the worlds recognition of the lighthouse.

A close-up view of Presque Isle Light Station in 2004. Authors collection.

From the beginning, sailors have had a particular need for light. They recognized that the hazards of navigation were challenging enough in calm and daylight situations, but when night and severe weather worked together to create low visibility, navigation at sea could become all but impossible. As the worlds nations began to use the seas to trade, the need for navigation aids such as lighthouses increased tremendously.

Once Spain, England, France and Holland all began to establish colonies and settlements in North and South America, shipping and trading grew at rapid rates. The need for more lighthouses, especially on the North American shores, quickly became evident. However, it was in the Caribbean, where the Spanish had an enormous influence, that the first lighthouse in the New World was built. It was constructed and opened in 1563 on the island of Cuba on the shores at Havana. It was named the Morro Light of Havana.

The first lighthouse in North America was authorized by an act of the English assembly and built by the Massachusetts Bay Colony at the entrance to the harbor of Boston in 1716. This lighthouse sits on Little Brewster Island, about eight miles from Boston, and has been designated a National Historic Landmark. During the Revolutionary War, the British destroyed part of it, but it was rebuilt with a new eighty-nine-foot tower in 1873. Records indicate that there were only seventy lighthouses in the world during those early years. A dozen or so of them were on the Atlantic coast of North America. Today, this lighthouse, known as the Boston Light, is the only light still manned by resident keepers. The light is serviced today by three active-duty U.S. Coast Guardsmen, and all hold the designation of lighthouse keeper. As a gesture of respect for a very old and venerable occupation, the Boston Light continues this worthy tradition of service.

For the next one hundred years, many new lighthouses dotted the coastlines of Canada, the English colonies and, finally, the new United States of America. Wherever ships ventured, the need for a lighthouse soon followed. The English colonists and colonies led the way in lighthouse construction along the eastern coast of North America. Soon after the American Revolution, individual states assumed responsibility for the lighthouses in their areas.

However, in August 1789, one of the first acts of the newly formed United States Congress was to assume the responsibility for all navigation aids within the new nation. It has been said that this act was passed due almost entirely to pressure from President George Washington. Washington, once a surveyor by trade, wanted to have the ability to appoint lighthouse keepers, negotiate with contractors and supervise the building of any new lighthouses. Both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, the next two presidents, also carried on this tradition. The first two lighthouses built under this legislation were Maines Portland Head Light and the Old Cape Henry Light in Chesapeake Bay. These lighthouses were built under President Washingtons direct supervision. He also appointed the keepers of both lights and continued these practices for seven additional lights in the following years.

During the early years, all lighthouses were officially placed under the Department of the Treasury. Much like what sometimes happens today, a department that is assigned a particular duty by an act of Congress may be unprepared and unwilling to take responsibility for the management of its new duties. When this delegation of lighthouses responsibility came about, it was a total surprise to the Department of the Treasury. Within the department, the responsibilities and management of this new area became like a ping-pong ball and bounced all over its various internal offices.

Finally in 1820, the responsibility for all the lighthouses was given to Stephen Pleasonton, a fifth auditor within the Department of the Treasury. Even back in the early days of the republic, the audit area of this department was widely known for passing paper from desk to desk and getting little accomplished. Pleasonton, who was a passionate bean counter, was given the title of general superintendent of lights. He was a bookkeeper and had no experience in any of the fields related to his new duties.

All knew him as the perfect practicing bureaucrat. Right from the start, Pleasonton failed to realize his real duty involved the lives and safety of the ships, crews and passengers. His actual responsibility was to provide all of them with the best navigation aids possible, and cost should have been a secondary issue. Unfortunately, during the time he held this position, his only focus was on economy and never on quality or safety.

Next page