Book 4

RESISTING NAZI OCCUPATION

The Dutch in Wartime Survivors Remember

Edited by

Anne van Arragon Hutten

Mokeham Publishing Inc.

2012, 2014 Mokeham Publishing Inc.

P.O. Box 35026, Oakville, Ontario, L6L 0C8, Canada

P.O. Box 559, Niagara Falls, New York, 14304, USA

www.mokeham.com

Cover photograph by Hein Bijvoet

ISBN 978-0-9868308-5-3

Contents

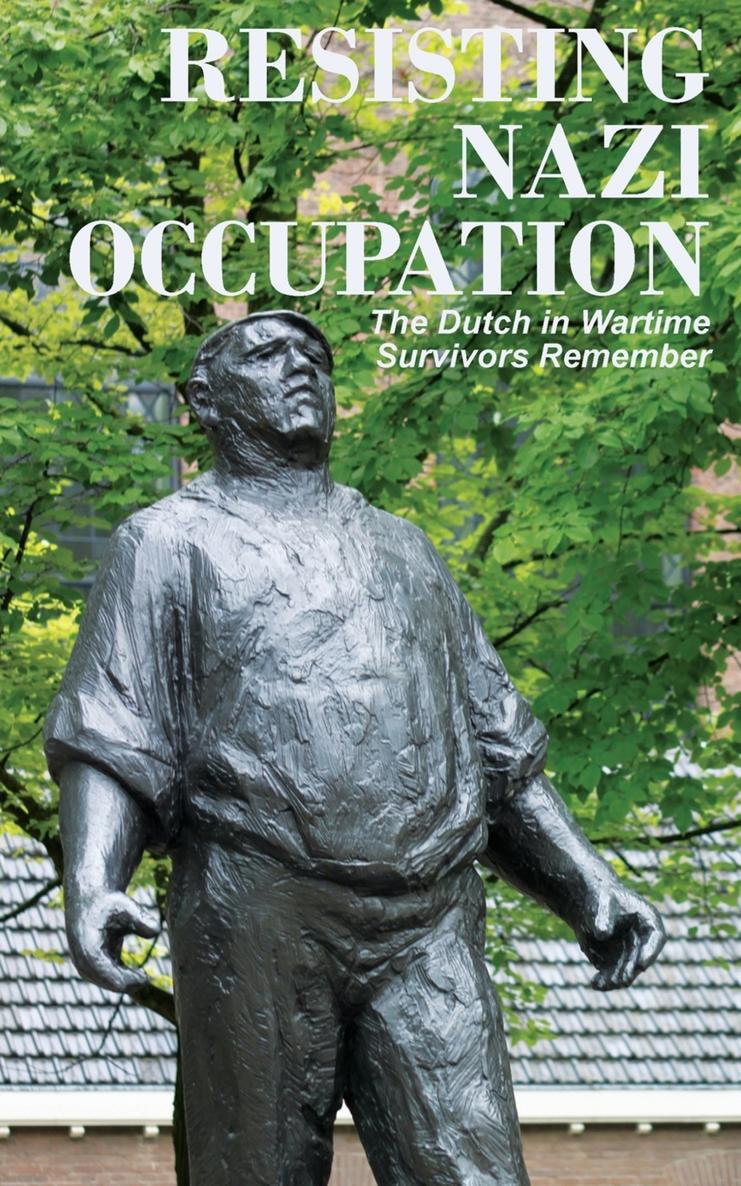

On the front cover

The Dockworker commemorates the bravery of the workers of Amsterdam and surrounding areas who went on strike in support of their maltreated Jewish compatriots in February of 1941. The February Strike was one of the first organized acts of resistance by the Dutch, and resulted in brutal oppression by the Nazi regime.

The statue was created by Haarlem sculptor Mari Andriessen and unveiled by Queen Juliana in 1952. It was placed in the centre of Amsterdams Jewish district - at the time virtually deserted after the Holocaust.

The monument depicts a labourer, strong arms held wide in a gesture that shows both a desire to fight back and an offer to protect. The statue symbolizes how ordinary everyday people called upon hitherto undiscovered inner strength in their fight against the oppressor.

An annual commemoration ceremony takes place at the statue on February 25.

Introduction

Anne van Arragon Hutten

A s was noted in the previous three books in this series, we are publishing the wartime memories of ordinary Dutch citizens. Despite the hundreds of books already written about the war, the stories continue to pour out. The impact of World War ll was so traumatizing that anyone who lived through it continues to feel its effects even into the 21st century.

My grandchildren all know that Grammy was born in the war. I was only four when the war ended, and nevertheless it has strongly influenced the person I have become. No doubt those who were teenagers or adults at the time will have far more personal war memories to share, but the war affected everyone, even the unborn and the infants of that time. I have spoken with other Dutch-Canadian immigrant women who, like me, really dislike working at a community supper where so many leftovers have to be thrown out. We are too aware that food is a vital resource. Wasting food feels like a sin, not just because it was so scarce during that war, but because millions of people today still go hungry.

If some of us tend to be unusually intense and serious, it is because so early on we sensed the fear and insecurity of living under a deeply evil regime. Life isnt all fun; shallow pleasures are fleeting. Actually, life itself is fleeting, here today and gone tomorrow. That was a hard-learned lesson of World War ll, and even those of us too young to understand it absorbed it into the marrow of our bones. The sound of endless waves of bombers passing overhead during the night in that last winter of war drove home the message: be afraid, because that bomb can fall on you.

It may not have been that way for everyone. As was demonstrated, particularly immediately after the war, many mostly young people went overboard in their search for freedom and fun. Many tried to live in a lighthearted spirit, enjoying life while they had it. Why waste time thinking about death and destruction? Behind that outlook I still detect the war: lets enjoy life while it lasts.

Most ordinary Dutch people probably had little time for such thoughts while they coped with an irrational enemy whose cruelty seemed limitless. Some found it easier to just go with the flow. If Germany was all-powerful, why resist? Might as well do as they say, and even work with them to keep our stubborn neighbours in line. There were plenty who collaborated with the enemy, betraying the young man hiding next door, or the visiting blonde niece from Amsterdam with the dark hair roots.

A large majority of those ordinary wartime people refused to travel that traitorous route. The Dutch, as a people, have long valued freedom of speech, of religion, of choice. They were not going to roll over and play dead as the Nazi war machine rolled over them. In many small ways they resisted, whether by burying their copper pans in the back yard or by hiding one or more young men in their homes to protect them from slave labour.

It is their stories we want to tell in this book.

Historical background

T he Dutch Resistance movement during World War ll consisted of many individuals and small groups, working under cover of their legitimate careers, or under cover of darkness, often with false identity papers.

Soon after the Germans invaded the Netherlands, various organizations sprang up to protest the blanket propaganda, the sly insinuation that the Germans and Dutch were all Aryans, and thus all on the same side.

In February of 1941 a strike broke out in Amsterdam and surrounding areas to protest the singling out of Jews for exclusion from many careers and public places, and the first violent round-ups of Jews. Students went on strike that same year, as did metalworkers who hated to see their work support the enemys war effort.

Eighteen prisoners were executed on March 13, 1941 for working against the occupiers. These included organizers of the February Strike and members of a group that had published chain letters and pamphlets calling on Dutch citizens to reject German orders and doctrine. These men had all operated fairly openly, without much consideration for secrecy and security. The mass killing shocked many Dutch into recognizing the true character of the Nazi regime. From then on the Resistance movement went underground.

By the end of 1941, various organizations had started to produce and distribute illegal newsletters and newspapers to keep the Dutch people informed about what was really happening, with other media firmly under German control.

Late in 1942, several small resistance groups were combined to form a national organization to help those who had gone into hiding for any reason. This group was notable for being unarmed. They included people from all walks of life. At first it was mainly the Jews who had to be hidden and protected, but as the war went on, more and more people found their life to be in danger. Very often these were the young men who, according to German demands, should have meekly lined up at the curb to wait for transportation to Germany. Not being on the official population rolls any longer, those in hiding no longer received ration coupons for food and other necessities. These now had to be supplied somehow.

Other groups did take up arms. They robbed distribution centers for those necessary ration coupons. They also raided prisons to free captured Resistance workers. As the war progressed more people went into hiding and it became necessary to feed them somehow. According to most estimates, between 300,000 and 350,000 people were forced to go into hiding, especially after participating in a number of strikes that were unsuccessful in stopping the occupiers. In April and May of 1943, spontaneous strikes erupted over the threatened imprisonment or forced labour of Hollands former military personnel.

It was largely these latter strikes, ongoing over a two-month period, that finally convinced the German leadership they would never win the hearts and minds of the Dutch, and their restrictive measures became ever more severe. The railroad strike in September of 1944 not only failed to lift the heavy hand of the oppressors, but also caused them to actively blockade food supplies to the cities.