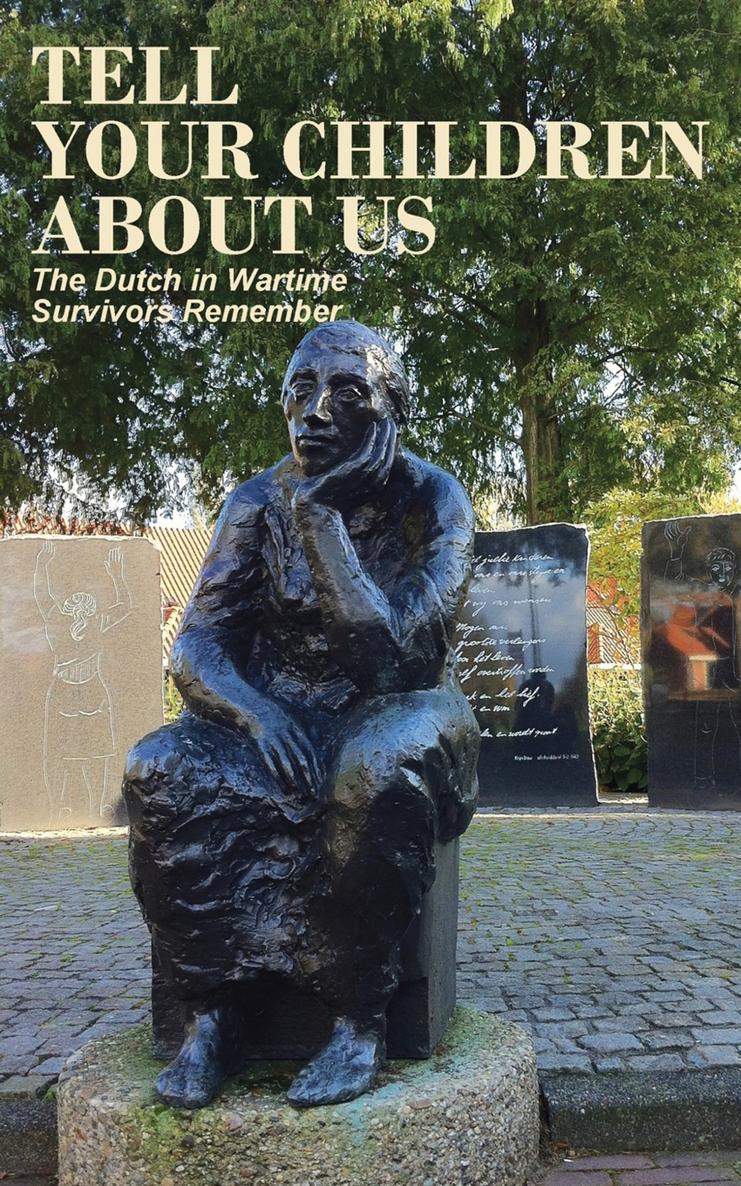

2012, 2016 Mokeham Publishing Inc.

PO Box 35026, Oakville, ON, L6L 0C8, Canada

PO Box 559, Niagara Falls, NY, 14304, USA

www.mokeham.com

Cover photograph by Sanne Terpstra

ISBN 978-0-9868308-6-0

Introduction

Anne van Arragon Hutten

A year or two before my Aunt Gerda died, she told me the story of her wedding dress.

All my life I had heard stories and read books about the war and about the shortages of everything we normally consider essential, but her story drove it home for me.

The year was 1945, and she was getting married at last. Like all brides, she started thinking about a wedding gown. And like most rural brides in the province of Overijssel of that time, it would be a black dress, with perhaps a bit of lace trim at the neck. But where to get such a gown? The stores were empty, and fabric could not be bought at any price.

Gerda knew who to ask. One of her older sisters, Mina, had two seamstress diplomas and could sew anything. And as Gerda had hoped, Mina came up with a solution. She managed to get her hands on two old mens overcoats, which in those days had a silk lining. She removed the lining with great care, carefully took apart every seam, washed and ironed it. Then she laid pattern pieces on the fabric and began cutting. The end result was an elegant gown that Gerda was proud to wear.

Mina, as it turned out, became my mother some years later, and that gives this story extra meaning for me. But mostly Gerdas wedding gown represents the ingenuity, the creativity, and the sheer stubborn resilience displayed by the Dutch in general, when they refused to lie down and cry in the face of so much deprivation. As you will read in this book, the population of Holland used their wits in dealing with an oppressor who stole all that was rightfully theirs, leaving the rightful owners without sufficient food, clothing, and footwear.

The Germans requisitioned (read: stole) whatever they wanted. They needed ships for their ultimately unsuccessful quest to conquer England, and Hollands fishermen were required to give them up even though that meant a complete loss of their livelihood. They needed copper, and not only was every household required to bring copper items to the town hall, but even church bells were taken down to be melted down for the war effort. They needed bicycles for their troops, and each family had to hand one over. Germany had drafted so many of its men to fight their war that hardly anyone remained to work the factories that made the weapons, and so even men and boys were requisitioned, or rather, forcibly taken.

How does a small country like Holland continue to function without the necessities of life? Obviously, it did so with great difficulty. And yet people carried on, trying for some semblance of normality. Children still went to school, until school buildings were requisitioned too, or a lack of fuel made it impossible. With one-third of a million men in hiding, many women and boys took over the responsibility of obtaining food and fuel, the most basic requirements everywhere. Children as young as six served as couriers for underground newsletters. Families continued to celebrate birthdays, Saint Nicholas, and Christmas, however meager the food.

They somehow absorbed the continually increasing loss of freedom, loss of property rights, and even the loss of family members to slave labour, captivity, or death. Its the British who are famous for keeping a stiff upper lip, but it seems to me that the wartime Dutch may have demonstrated this quality in equal measure. The Dutch never lost their hope that eventually Hitlers reign would end, that liberation would some day come. In the meantime they simply endured all the hardships, not knowing that the worst was yet to come.

This volume of The Dutch In Wartime mostly deals with the personal stories of families and individuals who carried on despite aerial battles overhead, V-1 and V-2 rockets crashing prematurely, hostile German soldiers on every street corner and sometimes at the door in the middle of the night. The ultimate battle to liberate the country, and the Hunger Winter that preceded it, still lay mostly in the future.

Historical Background

Tom Bijvoet

A s the occupation lasted longer, and ever more resources were being drawn out of the occupied territories to fuel the German war machine, the outlook for Hollands civilian population became increasingly bleak. Rations were getting smaller. And what little there was, was often of inferior quality. Clothing, shoes, furniture, everything had to be made to last and many items were falling into disrepair and had to be continually patched up. Commodities and services that even in the impoverished pre-war depression years had been taken for granted, were becoming luxury items: soap, fuel, and transportation among them.

And there was no end in sight. The long anticipated second military front that had been hoped for first in 1942 and then expected in 1943 did not seem to want to materialize. By the spring of 1944 the occupation had lasted for four full years. Four full years of repression, scarcity, the struggle to put a meal on the table, to clothe ones family, and heat ones home. A struggle that often did not deliver adequate results.

Although most peoples lives were not in immediate danger, there was always the risk of becoming an unintended victim of friendly fire. Allied bombs intended for military or industrial targets would occasionally miss and fall on city neighborhoods, as happened among other places in Rotterdam on March 31, 1943 (400 dead), Amsterdam on July 17, 1943 (150 dead) and Nijmegen on February 22, 1944 (800 dead). An Allied plane on its way home from a raid on Germany could be hit by flak and crash into a farm, village or town and Allied aircraft could strafe trains and ships carrying civilians that were mistaken for, or combined with, military transports.

Starting in mid-June, 1944, hundreds of V-1 and later V-2 missiles were launched from Dutch soil, aimed at targets in England and Belgium. When a launch failed, as happened on occasion, these flying bombs often dropped on nearby neighbourhoods. And then there was the ever present danger of being rounded up by the Germans in an act of retribution against Resistance activity or being sent to Germany to work in factories that were bombed almost daily by the Allied air forces.

When finally on June 6, 1944 the Allied landings in Normandy took place there seemed to be light at the end of the tunnel. The Allies progressed rapidly. They liberated Paris on August 25, Brussels on September 3, and Antwerp on September 4. By Tuesday, September 5, it seemed as though the liberation of western Europe was all but over. Rumours, some misinformation in an English radio broadcast, and four years of pent-up hope led to the widespread belief that the Allies had already reached Holland and that the country would be free within a matter of days. Chaotic scenes ensued on this day, which has become known as Crazy Tuesday. Germans and collaborators fled east, people who had been in hiding surfaced and streets were lined with flag-waving citizens awaiting the first Allied troops.