Copyright 2019 by Sophie Poldermans All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

SWW Press (Sophies Women of War Press) The book was translated from Dutch into English by Gallagher Translations.

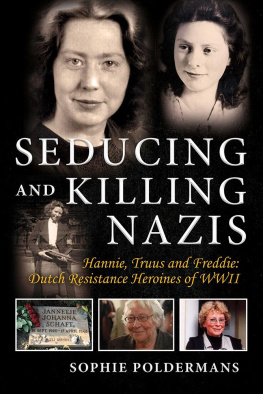

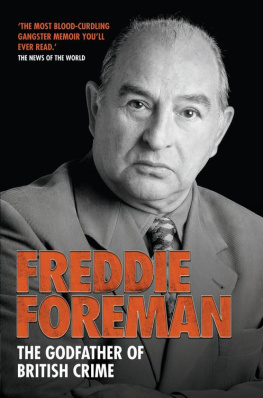

Front cover photos: (top, left to right) Jo (Hannie) Schaft, 1943 (photo by Cas Oorthuys); Freddie Oversteegen, 1945; (middle) Truus Oversteegen with Sten gun, WWII. These three old portraits are all Courtesy of North Holland Archives; (bottom, left to right) gravestone of Jo (Hannie) Schaft, 2018 (photo by Sophie Poldermans); Truus Menger-Oversteegen at an exhibition of her art work at North Holland Archives, May 3, 2008 (photo by Jaap Pop); Freddie Dekker-Oversteegen, 2000 (photo by Maarten Poldermans).

Back cover photo: Sophie Poldermans, Haarlemmerhout, 2018 (photo by Jaap Pop).

Interior illustration credits appear on pages xiii-xix.

Print ISBN: 978-9-08300-340-5

eBook ISBN: 978-9-08300-341-2

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA www.sophieswomenofwar.com

www.seducingandkillingnazis.com

To Sabine

You shouldnt ask a soldier how many people he shot. I was also a soldier, a little one, a child soldier, but I was a soldier.

Freddie Oversteegen

If you have to make a decision, that decision must be a right one and you must always remain human.

Truus Oversteegen

In My Minds Eye

In my minds eye, I see you all

still clear as day

no tears wash that away

no present fades the picture

and yet, I felt the beat

of new life, in my life

and once again a tower of yelling

cheering children outside

no tears wash them away

no past can fade them

they are the ones to bear the future!

Truus Menger-Oversteegen,

from Op het netvlies van mijn denken (In My Minds Eye) , 2010

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

A s the daughter of an archaeologist and A human geographer, historical awareness and the importance of humanity were instilled in me. I was taught to always treat another person equally and with respect, whether the person was a cleaner or a manager, a man or a woman, regardless of their cultural, economic or social background. I was taught to embrace and cherish freedom and to seize opportunities to develop myself. These were the ingredients of a strong sense of justice that were rooted in me from an early age.

Hannie Schaft was 19 years old when the Second World War broke out. Together with sisters Truus and Freddie Oversteegen, who were 16 and 14 years old at that time, Hannie Schaft was one of the few young womengirls stillwho took up arms against the enemy in order to honor the ideal of a livable world.

I have always cherished the ideals of these three young women. They run like a common thread through my personal and professional life. I was Freddies age (14) when I read Harry Mulischs novel, The Assault . This novel is about a family in the city of Haarlem, 12 miles west of the Dutch capital Amsterdam, in the Netherlands. This family is confronted with an attack on a collaborating police chief during the Dutch famine or Hunger Winter of 19441945 and is torn apart by the subsequent reprisals of the Germans. I was immediately fascinated by the injustice of the Nazi regime. I studied the Second World War in Haarlem and also the resistance fighter Hannie Schaft, who was the model for the main character of Mulischs novel.

I was captivated by Hannie Schafts life story and could certainly identify with her. I was also a teenager growing up in Haarlem, although fortunately under very different circumstances than Hannie. I started researching her life and her resistance work, which introduced me to the Oversteegen sisters.

When I was Truus age (16), I had to write a thesis for my history class in high school on a self-chosen topic. For me, that topic was obvious: Hannie Schaft. I was very dedicated and dove into the subject. When I discovered Truus contact details and called her up for an interview, she was so kind to invite me over. I remember that visit on a cold morning in February like it was yesterday. Truus could easily have been my grandmother, feeding me cookies and asking me if I liked her new glasses. But underneath that granny surface lay a whole different world. Her hand that shook mine when she invited me in, had held a gun, a gun that she had actually used to kill people. Although her targets were the enemy, they were people nevertheless. Over tea, she started telling me her story and that of Hannie and her sister Freddie, emphasizing its value for future generations, like mine.

When I submitted my final thesis to the National Hannie Schaft Commemoration Foundation, I was chosen at Truus request, to be the keynote speaker at the annual Hannie Schaft Commemoration in 1998. When my speech was addressed as expressing the strength of womanhood, I knew that I was thirsty for more and wanted to further deepen my research. I got acquainted with Freddie, who told me her side of the story and who encouraged me to continue my exploration.

When I was Hannies age (19), I started law school in Amsterdam, because just like her, I was interested in international law and the role of the United Nations in the setting of international peace and justice. At Truus invitation, I joined the board of the National Hannie Schaft Commemoration Foundation (now the National Hannie Schaft Foundation). During these years as a board member, I got to know Truus and Freddie (both board members at the time) very well and was able to learn a great deal from them.

I knew both women for almost 20 years and worked closely with them for over a decade. I always admired these women for their strength, for their ability to look ahead and for their continuing faith in humanity, despite their own experiences and sacrifices.

How do you stay human in inhuman circumstances? As I was pondering this question, immediately another difficult question arose as to what I would have done if I had grown up in circumstances similar to theirs. This was the beginning of a personal quest for identity, for answers to moral questions and for evolving intrinsic leadership skills.

During my law studies, I developed an interest in wars and all its facets. On the one hand, I became fascinated by the fact that people are evidently capable of committing crimes against humanity. On the other hand, I drew hope from the fact that in such circumstances, there are always people who go to extraordinary lengths in order to embrace their ideals, to combat injustice and to believe in mankind.

We live in a world still dominated by men. As far as wars are concerned, women are often portrayed as the main victims, while it is often precisely women who resist under such circumstances and show genuine leadership.

In a globalizing world, we meet more and more people from different backgrounds, people who have fled from wars. Let us not exclude these people but, rather, take them into our midst and listen to their stories.

From a legal perspective with a multi-disciplinary approach, I have further explored the role of women in times of war. It is exactly these women who deserve our attention.

After living and travelling all around the world, I recently moved back to Haarlem with my family. Sitting at my writing desk, I can see the Haarlemmerhout from my window, the spot where Hannie, Truus and Freddie seduced high-ranking Nazi officers, lured them into the woods and killed them. These three young women never saw themselves as heroines, they did what they did because it had to be done, because they believed in justice and because they never let go of their ideals. Across from my desk stands one of Truus miniature sculptures of Woman in Resistance, depicting Hannie Schaft, on an antique side table. I look at it every day, reminding me that we need strong female role models. We did then, we do now and we will in the future.

Next page