Acknowledgement

W riting this memoir took fourteen months of hard work, burning over 1,500 hours of evenings and weekends. It was indeed more than I had estimated but, as an engineer, Im used to projects taking more time than initially scoped.

Getting this memoir to print reminded me of visiting the Uffizi Museum in Florence. While admiring the antiquities, especially the exquisite marble statues, I contemplated the amount of work it took to complete each of them. Someone had to sever the blocks of stone from the quarry. Sculptors removed the excess material before carving the larger features, followed by all the intricacies. Finally, hours upon countless hours were spent polishing every curve and facet. They produced amazing works of art, but I would rather write a book.

Those sculptors had teams of helpers, and like them, I had a small team that assisted me. Id like to recognize some of the members of my team.

First, my appreciation goes to several friends and colleagues for the many hours spent providing me with valuable critiques and suggestions.

Turning to editing, I am lucky to have had three special people who offered their valuable and professional assistance. One of my few lifelong friends, John W. Marshall, helped me with the initial development, editing, publishing, and marketing. He, like those who removed excess marble from the slab, helped me reveal and convert my stream-of-consciousness-splattered draft into a framed manuscript.

Krista Haraway, a local up-and-coming freelance editor, provided line and copy editing that helped me with the chiseling of the rough and fine details, as well as providing insight from a younger readers perspective.

Dona Pratt, with a diverse career in software design, project management, and marketing, graciously took on this novices first-time work and contributed hundreds of hours to execute the sorely needed final polishing that elevated my mid-level grammar engineering draft into a professional work worthy of publishing.

Without John, Krista, and Dona, it would have been impossible to arrive at market. Thank you all.

Finally, utmost appreciation is extended to my wife Judy, who, for the past year, put up with my self-imposed confinement in our home office.

Dedication

A ny one persons life is affected to various degrees by loved ones, friends, family, bosses, and peers. My life is no different. Many people have made an impact on me by redirecting my goals, saving my butt in troubled times, teaching me valuable lessons in life, providing opportunities along the way, and giving critical advice in times of need.

Starting with my formative years, my father, Howard, was my first influence, and he continued to be a positive one until he died. My brother Fritzs mentorship was a presence from age 8 or so until I moved to California. My mothers brother, Richard (Duane) King II, used his technical and practical knowledge to inspire and coach me.

The women in my lifemy mother, two grandmothers and maternal great-grandmotherexemplified the more subtle, but important, behavior and characteristics that cant be described using an engineering vocabulary. Their contributions to my life, while not appreciated at the time, have been very much valued as an adult.

Tom Bridgen, whom we sadly lost last year, gave me employment opportunities and challenges that expanded my mechanical abilities and taught me about the broader world existing outside the farm.

From my professional career, I would say that Arnie Gunderson had the most substantive and consistent influence on my growth as an engineer. Credit also goes to my first engineering boss, George Rogers, from Pratt & Whitney and my Lockheed boss Gary Wendt, who saw talents in me that I had not recognized.

In addition, Id like to express my admiration for my lifelong friend, John W. Marshall; my former roommate, John Kenney; and a dear friend, Therise Doolin.

There were so many engineers that I had the great honor and privilege to know and work with during my career. Some I tried to emulate, some I looked upon in awe, many were significant contributors to our design efforts, and several are good friends. A few include a fantastic test engineer and calming force, Robert Ivanco; the absolutely brilliant engineers John Kalisz and Al Gegaregian; a wise and talented boss, Chris Fylling; an engineers engineer, Mark O. Wise; the best stress engineer I have worked with and close friend, Tauno Kartiala; a really talented engineer who unfortunately passed way before his time, Carl Glahn; a longtime friend, Dennis Failoni; and another talented stress engineer, Steve Norman.

I have been so blessed to know and work with all of these people. I have admired their talents and tried to learn from the best of their characteristics, their tutelage, and their leadership along the way.

To all these people that Ive mentioned and many more who helped me along the way, I dedicate this work.

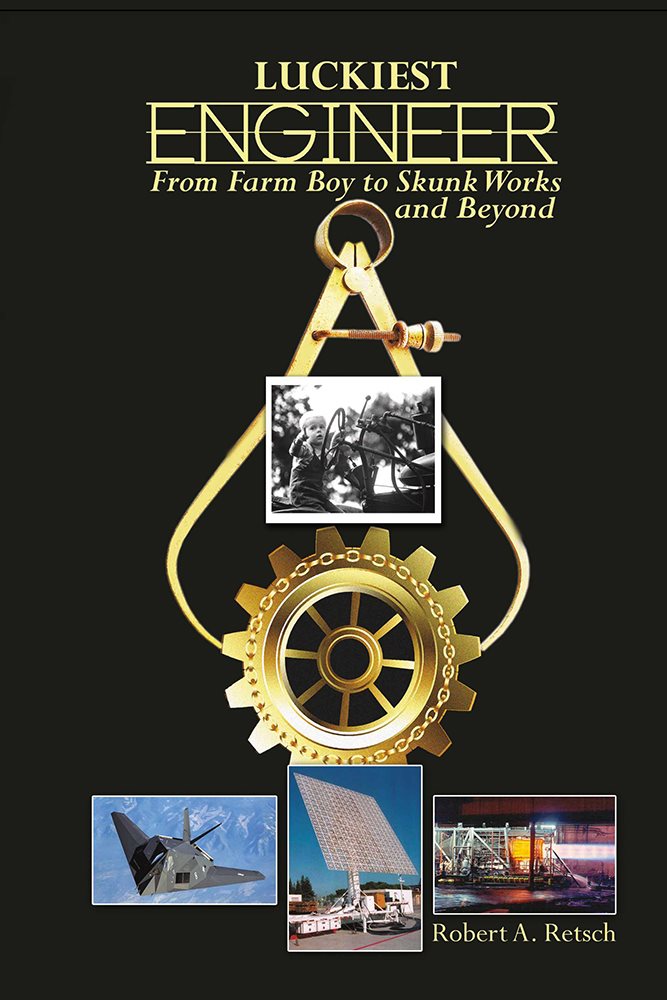

Musings from a B-737

T he vision for this memoir began one fall morning in 1983 on a company-chartered Boeing 737. It was 08:15 and I was commuting to work, sitting in a starboard side window seat. My fellow employees called the plane the Red and White. We had just taken off from the Burbank Airport and were climbing out northbound at around 6,000 feet, crossing over the peaks of the San Gabriel Mountains. The plane was headed for the not-to-be-disclosed classified test site somewhere in the state of Nevada. It is now known as Area

Reading page two of that mornings USA TODAY, I had just taken a sip of hot coffee handed to me by the flight attendant and placed it on the tray table of the empty middle seat. That day there were thirty-five to forty other employees on board: engineers, mechanics, analysts, and support personnel spread throughout the hundred or so available seats. Since it was early morning, the sun was just breaking over the eastern horizon and spreading warm yellow-orange rays of light through the window and across my right leg, illuminating the newspaper in my lap.

At that moment, and for some unknown reason, I paused my reading and reflected on how great life was for me!

Graduating from college at the delayed age of 29 with a mechanical engineering degree, I had been lucky enough to land a job at Lockheed Aircraft Company in Burbank, California in their Advanced Development Projects (ADP) department, also known as the Skunk Works. The program that I was assigned to was the highly classified F-117 Stealth Tactical Fighter, later to be named Nighthawk. I was earning more money than I had ever made, in a job that I loved beyond belief, working at one of the most innovative aircraft companies in the world. I was living in a beautiful house in the central portion of the San Fernando Valley with only a twenty-minute commute to work. Working on the F-117 Program, I was surrounded by the greatest aircraft design engineers in history. Although Kelly Johnson, the founder of the Skunk Works, had retired nine years earlier, he could be seen occasionally in the halls or parking lot. Ben Rich had taken over from Mr. Johnson at ADP and was my top boss. Sometimes it felt like I was living in a history book.

I thought, How many recent engineering gradsor any other engineers for that matterhave it this good? How many of them commute to work in a company-chartered Boeing-737? Who else ha s this amount of responsibility with such short tenure? Damn, I am one lucky engineer!

It took about fifteen seconds to process all these thoughts and then it was back to my newspaper. But those thoughts stuck in my mind and I revisited that moment often throughout my career.