Pagebreaks of the print version

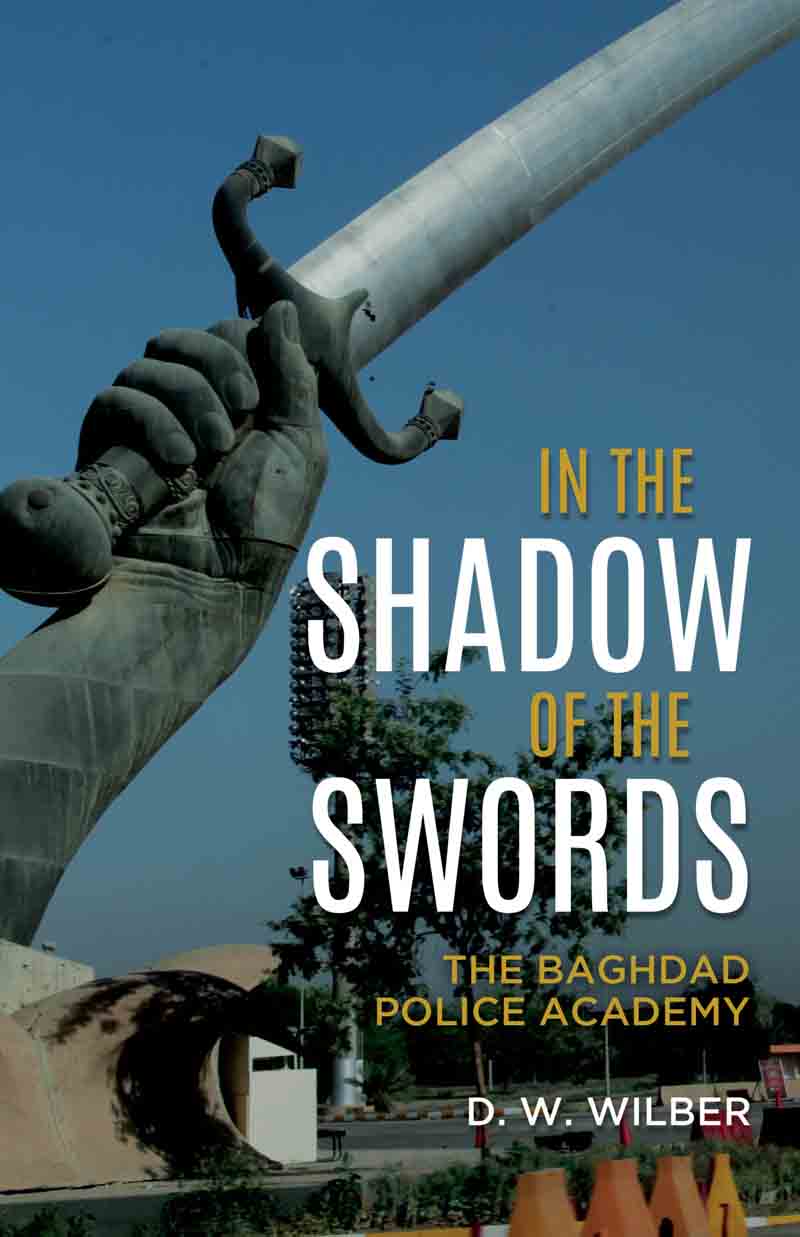

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SWORDS

The Baghdad Police Academy

D. W. WILBER

Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2020 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

and

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

Copyright 2020 D. W. Wilber

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-921-6

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-922-3

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

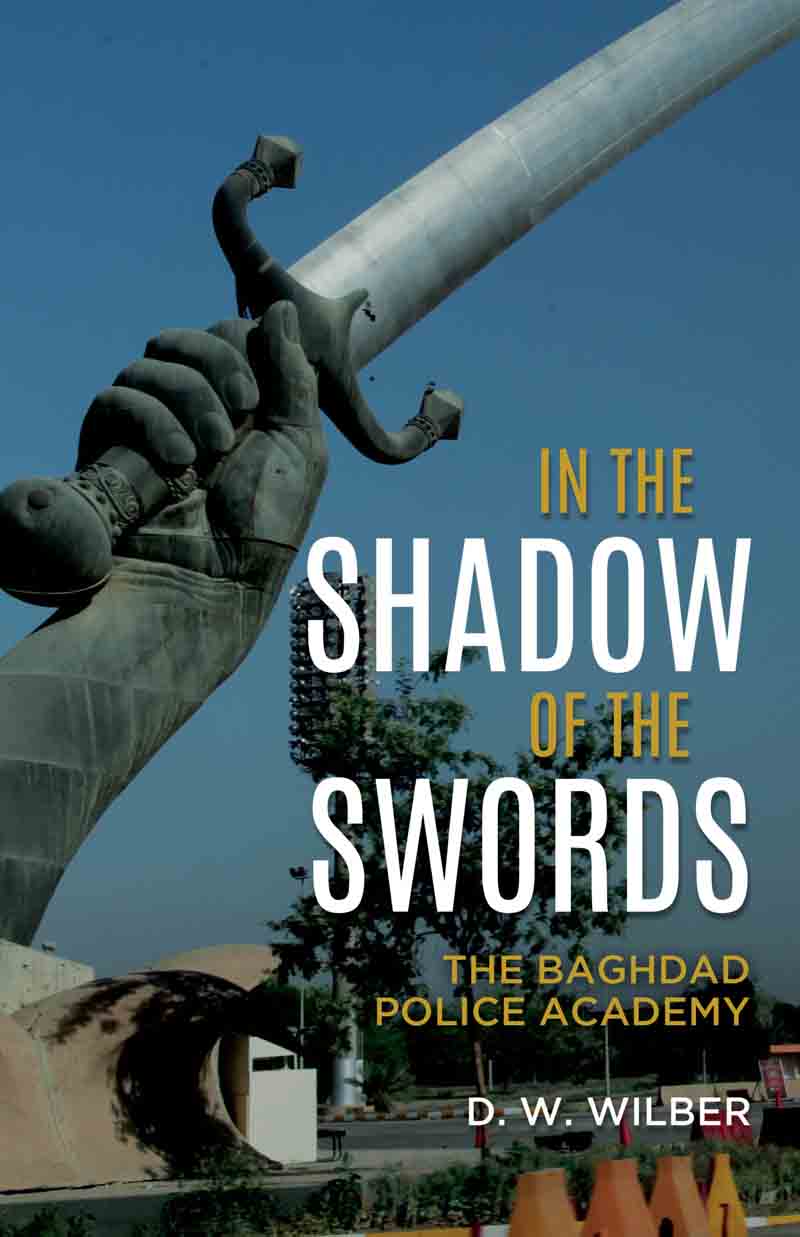

Front cover: The Crossed Swords monument in Baghdad, Iraq.

Julie, thanks for always being there

Jennifer, Lindsay and David,

thanks for putting up with your old man

Foreword

In the Shadow of the Swords will hopefully wake America up to the fact that there are dedicated men and women, not just in the military, who are working in harms way all over the world, trying to bring a semblance of order into societies and countries that in many cases have never known it, or at least not known it for decades or even centuries. Their work is particularly important and dangerous in the many so-called Third World countries that have been gripped by strife, war, or despotic and oppressive leaderships.

From the day President George W. Bush brought the War on Terror to Iraq, and up until the last American cop left the Baghdad Police Academy, men and women from law enforcement took the risks and accepted the challenges of working in a war zone to support U.S. policy and help rebuild Iraq. They dedicated themselves to improving the lives of innocent Iraqi people, yearning for a breath of freedom following the horror of life under Saddam and his regime, and the destruction brought to their historic land by an invading army.

This book looks through the eyes of the dedicated men and women who stepped up to this challenge. It also brings to light those who gamed the system and literally stole money from the American taxpayer, receiving generous salaries for duties not performed. It shares the recollections of working with bewildered Iraqi cadets, who lacked any understanding of Western law-enforcement tactics, methods, and (especially) police ethics. It highlights the impact on family members back home, who saw the carnage on the streets of Baghdad via the daily barrage of television news, and it reveals the hypocrisy of the bureaucrats in the Green Zone, who attended their embassy cocktail parties and stood inside Saddams palaces with arms folded across their chests, thinking deep thoughts. Ultimately, it opens up a conversation about the wisdom of any future efforts to bring American- or Western-style law enforcement to Third World nations.

There is also plenty of humor, as seen in the daily practical jokes and camaraderie that developed between a disparate group of American (as well as some foreign) cops, thrown together in the middle of a hot war zone. You will see how we survived and faced the immense challenges of just making it through another day. Photographs paint a visual history of the places and people who were brought together and who persevered through difficult times to establish a brotherhoodin-arms, understandable only by those who answered the call.

While many books covering the challenging events of Americas War on Terror have come from journalists, politicians or soldiers, not many have spoken of the effort from the viewpoint of a civilian contractor, sent to help rebuild Iraqi society following the fall of Saddam. This rebuilding included the restoration of government services, to bring back some semblance of normalcy to a society that had nearly been destroyed. As a long-time police officer and contractor in Iraq, I can tell a very different side of the story. This is not the viewpoint from the lofty towers of political appointees and senior officials, who have reputations to protect and records to defend, but rather that of someone who was on the ground, getting his hands dirty and seeing firsthand our successes and, sadly, some of our failures.

Youre making $14,000 a month and you want to complain? Tom Burnett said to the group of instructors who approached him with questions about the weakness of the training curriculum at the Baghdad Police Academy. I only have one thing to say, window or aisle? This phrase, window or aisle, became the almost daily refrain from those running the police training program in Iraq. It signalled that they really didnt give a damn about feedback from instructors on the front lines, dealing with the challenges of actually training police cadets. All the instructors felt that six weeks of training, conducted through a translator, wasnt nearly enough, barely scratching the surface of what the cadets would need to survive on the streets of Baghdad and elsewhere in Iraq. It is a difficult enough job on the streets of America, let alone in the extremely challenging environment of Iraq, where police were prime targets for an insurgency in full swing. But it seemed the program managers in the Green Zone were interested in only one thinggetting police officers on the streets as quickly as possible, with little regard for how well they were prepared. They were viewed as something akin to cannon fodderjust toss them into the lions den and if three-quarters of them are killed, so be it. That was the governing philosophy of the people in charge of rebuilding the Iraqi police force.

Their apparent opinion was that few knew or even cared about what was happening at an out-of-public-view training site in Baghdad, or any of the other locations around Iraq. And to be honest, most Americans simply didnt pay attention, or even know what we were doingwe didnt make the evening news. Back in the States, people were more concerned with what color to paint the spare bedroom, who to invite to next Saturdays cocktail party, or little Miss Buffys dance recital on Tuesday night. We kicked Saddam out of Iraq, and rather quickly at that, much quicker than we had prepared for, in fact. As far as the American public was concerned, what happened afterwards was someone elses problem. Those with family members in the military, or serving out there as civilians, certainly cared, but few others in America did. Nor did they really want to hear about it. We were out of sight, and easy to put out of mind.

No one knew about the American cops struggling to rebuild a police force that had been disbanded through the stupidity of American bureaucrats. Few Americans knew about people like my buddy Bob (Baghdad Boob) Manfreed, initially enticed to Iraq by the high salary, but who developed a genuine affection for the cadets he worked with each day. Not many Americans cared that instructors like my friends, and many others, were working in very basic conditions, often without even the barest necessities of life. Like toilet paper.

Instructors faced almost daily mortar attacks, as well as more simple challengeswith dozens of us packed into spaces designed for far fewer. Most Americans simply did not care that instructors had to deal with out-of-touch program managers in the Green Zone, who really didnt give a damn about us once they sent us out into the field, not even bothering to learn most of our names. These same instructors faced a constant threat of attack from within, by Iraqi cadets sympathetic to the insurgency, but no one really cared. The insurgency had developed out of the sheer stupidity exhibited by the career bureaucrats who had arrived in Iraq early after the invasion. They were the epitome of the saying, Im from the government and Im here to help. There was corruption, but sadly the American public has become conditioned to it in government programs, and most accepted that at least some was inevitable. Corruption in the Iraqi Police Training Program was accepted and, sadly, far too often ignored.