CHAPTER ONE

Russian Beginnings

an early taste for the stage

IDA LVOVNA RUBINSTEIN was born in Kharkov in the Ukraine. Unsure of the exact date of her birth, Garafola looked for her birth certificate and found it in Kharkov, in the Grand Choral Synagogue, written in both Russian and Hebrew, stating that she was born in September in 1883. Her parents were highly respected in upper-class Jewish circles with great riches both in banking and in the grain trade. They were considered among the wealthiest families in Russia, and despite the familys Jewish background, were privy to most of the same advantages that the aristocracy enjoyed. Rubinstein lost both her parents at an early ageher mother when she was five and her father at the age of eight, either from cholera, or typhus.

Rubinstein was taken from Kharkov in the Ukraine to live with her wealthy Aunt Horwitz in St. Petersburg, the Russian capitol founded by Peter the Great. It is a resplendent city surrounded and penetrated by waterways, like Stockholm and Amsterdam, and, scattered throughout the horizon are a series of Baroque structures, magisterial and lyrical palaces filled with art and the highest sense of Italian and French decorative styles. These opulent buildings represented the dying czardom and withering aristocracy soon to be thrown into oblivion in 1917. Although Russia, during the autocratic regime of Czar Nicolas II, ruling from 1894 to 1917, was dangerously arrogant, it was still a Russia full of hope for the future, with its wondrous nineteenth-century inventions such as the train, the telephone, the Belle poques fashion and style, the economic and modern industrial advances, the welcome freedom for the serfs, and a rich cultural environment with writers, composers, and artists inspired by European initiatives creating new ways and visions.

Walter Guinness, First Baron Moyne, 1918. Photographer unknown. SOURCE: BASSANO LTD., PUBLIC DOMAIN.

Ida Rubinsteins Russian home, 2 Angliskaya, St. Petersburg. SOURCE: AUTHORS COLLECTION.

But it also presaged continuing and monstrous acts endangering all Jews. Rubinsteins family, as rich as they were, certainly took account of the anti-Semitic outbursts in 1881 and 1882, as well as the profoundly hostile and frightening Kishinev pogrom in 1903 when forty-nine Jews were killed and 1,500 homes were destroyed. The Rubinstein family wealth, however, was known to be philanthropic, and they endeavored to place themselves in a modern industrial world. Rubinstein would never deny her Jewishness, but her quest for aesthetic perfection strove to supersede religious boundaries.

Contrastingly, Kenneth B. Moss, a distinguished scholar of Russian history, offers an illuminating comment to introduce a study of Ida Rubinstein: We should think about late imperial Russian Jewry not only as more Russian and more imperial than previously thought, but also as enthusiastic participants in the life of a modern society that afforded them the possibility of a vibrant cultural life.

The photos of Rubinstein in various libraries depict an enthusiastic woman of extraordinary character and, depending on the photo, multiple sensibilities and qualitiesfrail and imperial, sad and triumphant, seductive and aloof. When Rubinstein was growing up, the fashion for nude bathing and freeing the body of corsets and clothes was spreading across Western Europe. Being influenced by such views, she would not shy away from celebrating her body in her future productions. Her tendency to disrobe will be explored in later chapters.

Vicki Woolf, the author of Dancing in the Vortex: The Story of Ida Rubinstein, also comments on the disappearance of outward signs of Judaism in the Rubinstein/Horwitz family Though why Rubinstein did not attend university, with her inquiring mind, does cause some puzzlement. Perhaps it was because she always wanted to be in the theater. Woolf explores the idea that Mme Horwitz encouraged her niece to attend opera and ballet performances, especially since the court played a vital role in the activities of the imperial ballet and getting close to the court was the essence of upper-bourgeois aspirations. Horwitz and her niece were regular participants at the Maryinsky Theatre. But it became apparent to her family, when Rubinstein turned twenty-one, that she had no business attaching her hopes and dreams to a life in the theater. Rubinstein disagreed.

Not surprisingly, events in Rubinsteins life, although studied by very few writers, caused many scandals and much gossip. In an effort to uncover information and stories about her early years growing up in St. Petersburg, I sifted through comments from a number of authoritative sources. Details about Rubinsteins family fortune are few and often differ. For example, I found a 2015 Ukrainian article on Rubinstein online in the Jewish Observer titled Mystery Woman, a Russian-language text that speaks about her resistance to questions asked about her past. What it does say is that she was born to the parents, the father an honorable citizen of Kharkov, Lian or Leon Romanovitch Rubinstein and the mother, Ernestina Isaacovna. Rubinstein came from one of the most prosperous families in Ukraine and Russia. Her grandfather founded the banking firm, Roman Rubinstein and Sons. The family owned sugar factories, a brewery named New Bavaria, warehouses and stores.

Since Rubinstein was associated with a known and powerful family, as she was related to the Rothschilds and the Cahen dAnvers. Rubinsteins aunts, Marie Kahn and Julia Cahen dAnvers held glittering settings at their salons and were known as the Jewesses of Art.

Stronhina makes the persuasive point that wealthy Russians, especially from Jewish families, became important figures (mcnats) in the cultural landscape, offering an inexhaustible number of rubles to the parks, gardens, libraries, hospitals, and the arts, including museums. Wealthy Jews lived on the level of the richest and aristocratic, Marchands de premiere guilde. At the same time, if you were not among the gifted, there were strict prohibitions against Jews of a lower class, who were not allowed to live in the urban centers of Russia, but were relegated to the Ukraine, to the old boundaries of Poland, and Belorussia, and were treated on the same level as criminals. But privileges and permission to live away from the Jewish Pale of Settlement only came with large payments to the imperial treasury.

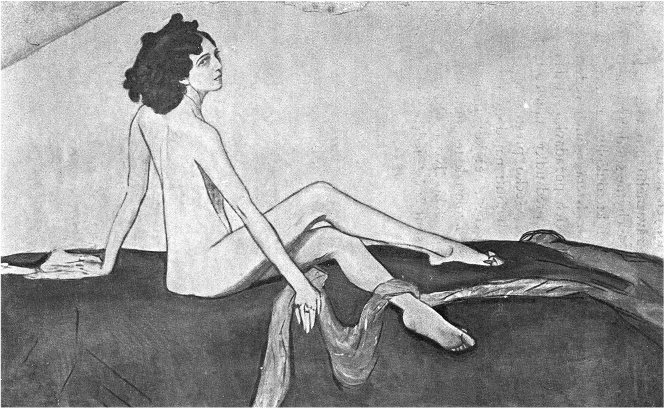

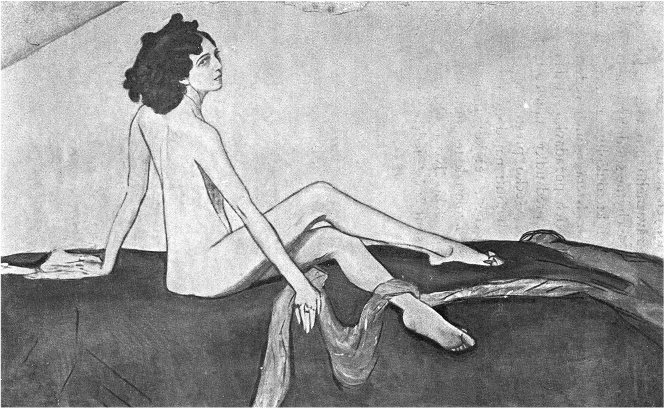

Ida Rubinstein, 1910. Portrait painted by Valentin Serov. SOURCE: UTCON COLLECTION/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.

Rubinstein grew up without religion, or croyancesbeliefs that, according to Stronhina, might have been detrimental and would have prevented her from developing into a freethinker and lover of all forms of art, literature, and languages. She opined that religion tended to restrict freethinking. Art became the spirituality that she sought all her life.

Stronhina also reminds us that Rubinstein is still remembered in Russia, perhaps not so favorably, for a number of reasons. The famous Russian portrait painter Valentin Serov painted an unusual singular image of Rubinstein reclining, naked and looking quite beautiful and enigmatic (1910). Long famous in France, she was quickly forgotten after World War II, despite many portraits and photos that kept her image in the news while she was alive. Russians disliked her seductive persona, believing that she lured Serov into an illicit affair that destroyed his marriage. The portrait remains and so in Russia she is remembered.