Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

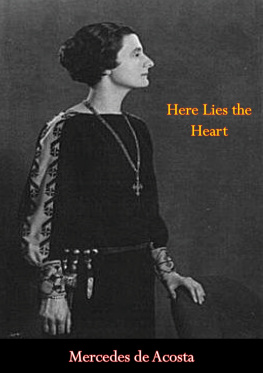

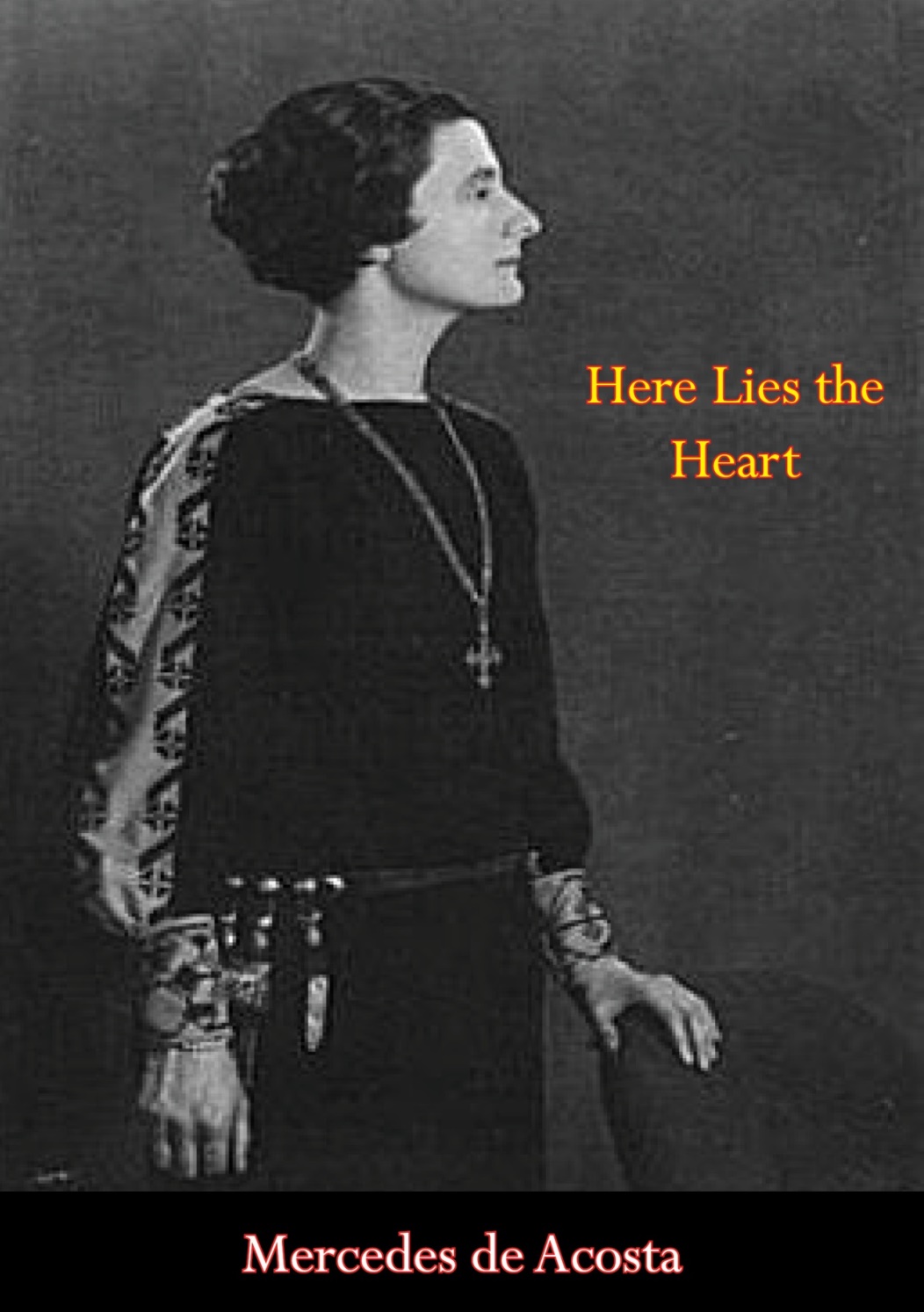

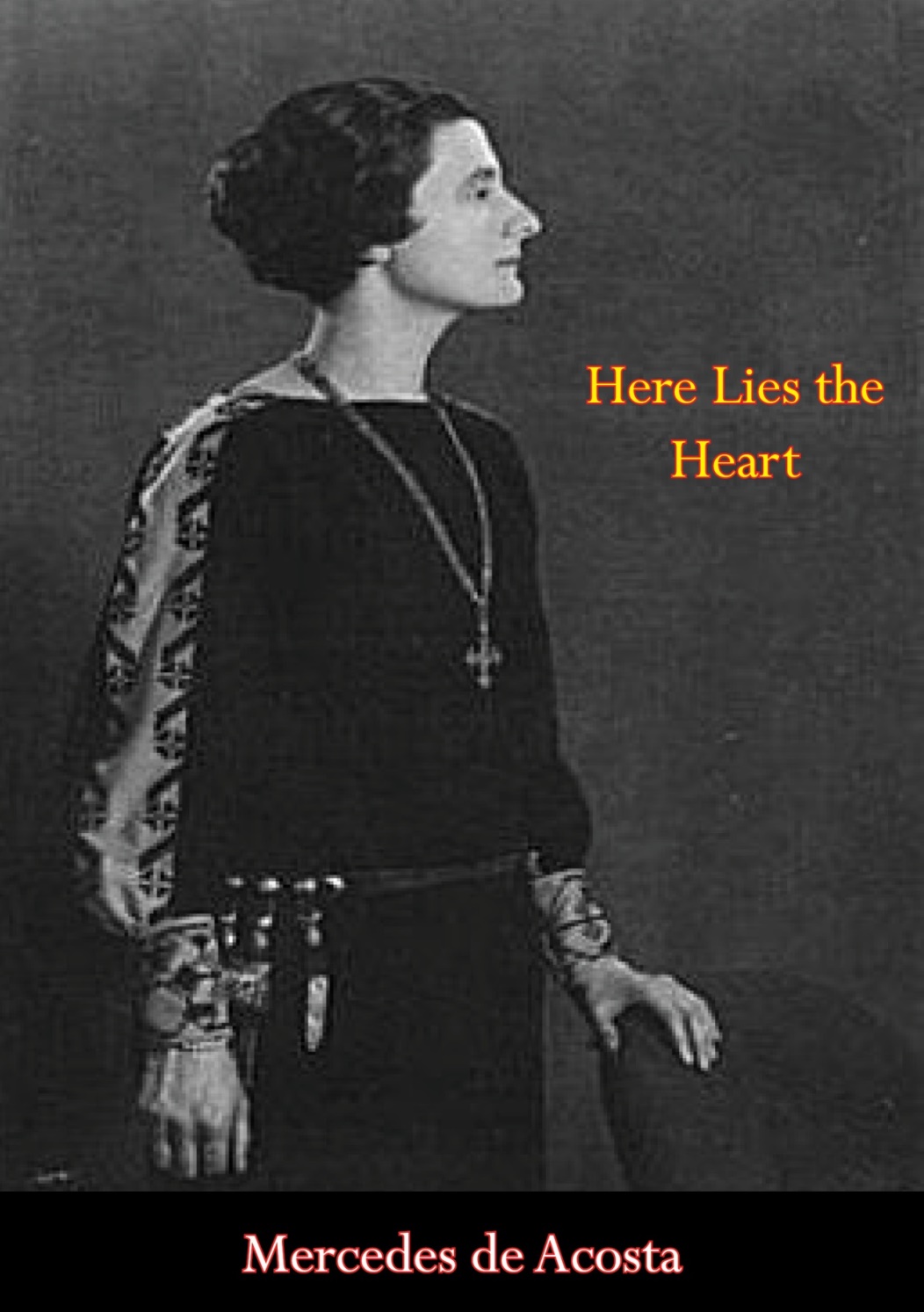

HERE LIES THE HEART

Mercedes de Acosta

Table of Contents

Contents

DEDICATION

TO

BHAGAVAN RAMANA MAHARSHI

THE ONLY COMPLETELY

EGOLESS, WORLD-DETACHED, AND PURE BEING

I HAVE EVER KNOWN

When I was young, the Spanish painter, Ignacio Zuloaga said to me, All great people function with the heart He placed his hand over my physical heart and continued, Here lies the heart. Always remember to think with it, to feel with it, and above all, to judge with it.

Many years later when I was in India in 1938, the great Sage, Ramana Maharshi, placed his hand on my right breast and said, Here lies the Heartthe Dynamic, Spiritual Heart. Learn to find The Self in it

The Enlightened One raised the artists counsel to a higher level. Both, at just the right moment, showed me The Way.

Here Lies the Heart

One

I was conceived in France and born in New York. If it is true, as it is maintained in India, that the place of ones conception has a marked influence on the subconscious, this, then, may be the reason why I have been drawn back time and again to France as though I had some affinity with that country.

I am by blood a pure Spaniard, my mother and father both having been Castilians as far back ancestrally as they could trace.

I was brought up mostly in America and France, but I have lived in many other countries and I am at home in many of them, and, I might add, equally lonely in all of them. I am, however, always grateful that I am a Spaniard in spite of the fact that, to my way of thinking, it is a handicap to possess a Spanish character. It imposes upon the consciousness a far too tragic sense of life.

Pure Spaniards are totally apart from other races and very little understood, and to have this heritage and at the same time to have been born in the United States is in itself a cause for psychological contra-dictions and complexes. The Spaniard, as a rule, is not adaptable. My mother and father, both transplanted from Spain to America, communicated to my brothers and sisters, and to me, a consciousness of a sort of homelessnessthat is, of not actually belonging to America. But having acquired a modern way of life there, we could not feel when we returned to Spain that we belonged to that country either. It is strange how far apart the brain and the heart can be. In my case, I believe that my mentality is truly international but somehow, try as I may to change them, my impulses and my heart too often remain Spanish.

I was the eighth child in my family of three boys and five girlswe were Joaquin Ignacio, Rita Lina Hernandez de Alba, Ricardo Miguel, Aida Marta, Maria Ccelia, Enriqu Jos, Angla Aloysius, (who has always been called Baba), and myself. Perhaps as the last child of so large a family, I suffered from the material having run out, as I expressed it. This theory I advanced at an early age as the reason for my spiritual and physical suffering.

The first thing I really remember was when I was six months old. A bear looked down at me as I lay in my pram in a place called Quoque, Long Island, where my parents had rented a cottage for the summer. In my childhood, it was not unusual to see men strolling the American countryside with trained bears. It was only a little unusual that he peered into my pramnot only peered but put his face close to mine to get a good sniff of me. I was not frightened. I am told that I tried to put my arms around his neck. I can distinctly recall the delight I felt in touching him, and the despair I sank into when the keeper pulled him away.

When I was about four, Maggie, my nanny, took me every morning to nine-oclock Mass at Saint Patricks Cathedral. At this time there was a Catholic orphan asylum opposite the Cathedral on Fifty-first Street. The children and some of the nuns of the asylum also came to the Mass. They occupied the pews on the left side of the main aisle. For some reason of her own Maggie always made straight for the first unoccupied pew directly back of the children and, pushing me into it, knelt down, so that it seemed to any observer that we were part of the orphanage.

While Maggie followed the Mass, engrossed in her prayers, I usually entertained myself by standing up to look over the people in the pews behind. One gentleman in particular received my special attention. I always stuck out my tongue at him. The gentleman happened to be Augustin Daly, who owned the famous Daly Theatre on Broadway and was considered the foremost theatrical producer of his time.

After some weeks of flirting and making faces at each other, Mr. Daly went to the Mother Superior of the orphanage and inquired if he could adopt me. From his description of me the Mother Superior was not unnaturally mystified as to which child of the orphanage it could be, so one day during Mass he brought her to the Cathedra] and pointed me out to her.

This child does not belong to the orphanage. I know her mother very well, the Mother Superior said. Mr. Daly was disappointed but, being a man who always got what he wanted, he persisted.

Maybe it could be arranged to let me adopt her anyway, said he. I have my heart set on bringing her up. I feel there is a great mutual sympathy between us. I am willing to make any financial arrangement with the mother that will enable me to adopt her. I am quite in love with her.

Mr. Daly had been quite used to bargaining with actresses, actors and authors, and had found that if he offered enough money, usually they could finally be coaxed to sign contracts. He was quite confident that a mother could be persuaded to give up her child by the same means.

My mother had been one of the first pew owners in Saint Patricks. She was a friend of the archbishop and a close friend of Father Lavalle who later became Monsignor. She knew all the priests of the Cathedral as well as she knew all the nuns in the orphanage, then attached to it.

Mother Ada Martha had a sense of humor. She decided to play a joke on my mother and at the same time, no doubt, teach Mr. Daly the lesson that there are some things in life not to be bought with money. She told Mr. Daly that she would arrange a meeting for him with my mother on condition that he would plead his own case. With his usual confidence he agreed. She then invited my mother to have tea with her to meet a charming gentleman who wished to ask her a favor.

My mother, in spite of her years in America, remained somehow unmistakably foreign, aristocratic, and very unusual looking. She spoke English abominably, with the worst kind of Spanish accent Mr. Daly had not imagined facing a woman like this. When, after presenting him, Mother Ada Martha left the room, Mr. Daly, no doubt for the first time in his life, found it difficult to talk money.

Next page