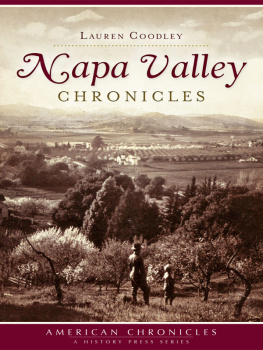

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Alexandria Brown

All rights reserved

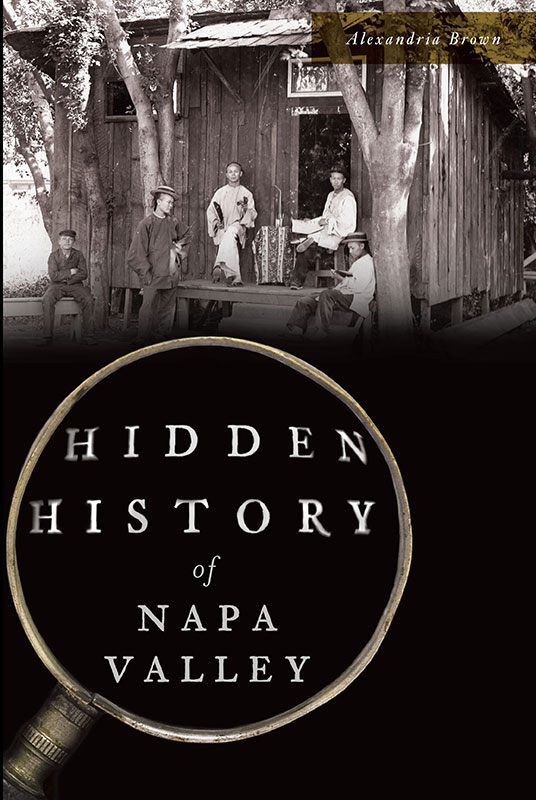

Front cover: This photograph of Chinese men in front of a building in the Napa Chinatown was taken by Mark Strong sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Courtesy of Napa County Historical Society.

First published 2019

E-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.627.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018963518

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.899.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my mom, who taught me how to be as determined, over-prepared and stubborn as she is.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is important for all of us to appreciate where we come from and how that history has really shaped us in ways that we might not understand.

Sonia Sotomayor

This book would not have been possible without the assistance and contributions of the following: Beverly Brown Healey, Dr. Amar Abbott, Dr. Sandra Nichols, Darin Ow-Wing, Karen Burzdak of the Napa Valley Genealogical Society, Breanna Feliciano of Napa County Library, Kathy Bazzoli of the Sharpsteen Museum, Lawrence Rodriguez of the Office of the Assessor and County Clerk/Recorder, Sharon McGriff-Payne, Chris Jepsen of the Orange County Archives, the Anne T. Kent California Room and the Marin County Free Library, Natalie Naranjo, Derek Anderson, St. Helena Historical Society, Rowena Richardson, Aurelio Hurtado, Juanita De Haro, Dr. Oscar de Haro, Timothy Reyes, Jeanette Fitzgerald, Bill Jensen, and Doug Patterson, Dorothy Hoffman, Diane Patterson and the rest of the Anton and Caterina Nichelini family. To my editor, Laurie Krill, and production editor, Sara Miller, thank you for helping me make the best possible version of this book.

To Presley Hubschmitt, Nancy Levenberg, Megan Jones and all the wonderful volunteers and board members at Napa County Historical Society, you went out of your way to help me on short notice, and I truly appreciate it.

And, of course, special thanks to my dedicated research assistant Jonathan Strange.

PREFACE

History, despite its wrenching pain, Cannot be unlived, but if faced With courage, need not be lived again.

Maya Angelou

Countless books, articles, documentaries and blogs have claimed to tell the real history of Napa County. Yet, nearly all of them tell different versions of the same story of how white men civilized the untamed wilderness and conquered the valley with grapes. The very mention of the Napa Valley conjures images of expensive wine and wealthy winemakers.

Hidden History of Napa Valley is not a history of wine, although winemakers do appear within. There are tales of lost cities, forgotten innovators and haunting ruins as well. But, mostly, this is a new look at the local history of marginalized people. As a queer Black woman who grew up in Napa, I realized early on that if I wanted representation, I would need to find it myself. I became a historian, archivist and librarian in order to do just that.

When I think of history, I think about the people all too frequently left out of traditional narratives. I consider why we choose to ignore their contributions and the consequences of our ignorance. Suffice it to say, there would be no Napa Valley without the subjugation of Indigenous people, the enslavement of African Americans, the exploitation of Chinese and Mexican laborers, the agricultural traditions established by Californio ranchers and European immigrants and the undervalued physical and emotional labor provided by women.

Through local history research come new revelations about the past and the people who lived it. Sometimes that changed perspective can be hard to accept, but it makes it no less true. To understand how the Napa Valley became the world-renowned region it is today, we must acknowledge the hundreds of thousands who struggled and sacrificed. Recognizing the truth of our past does not undermine our present but ensures an inclusive and honest future.

By no means is this book the whole story of every marginalized group in Napa County. Think of this as an introduction rather than an exhaustive history. Particularly absent here are the Japanese, who settled the valley only to be imprisoned in internment camps; the Filipino, Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander migrants and settlers who left their mark; religious groups like Muslims and Jewish people; and the still mostly hidden history of the LGBTQIAP+ community. Their contributions are very much worthy of study, and hopefully, future researchers will pick up where I left off.

PART I

FIRST PEOPLE

The white people came along and destroyed all these places.

Theyre just cutting us off when all our rights have been cut off.

Laura Fish Somersall

TALAHALUSI

Sometime between three thousand and ten thousand years ago, the first people arrived in what is now Napa County. Over time, the majority of the region would become home to the Wappo and Southern Patwin people. The territories of the Pomo and Miwok also crossed into present-day Napa County, but they predominantly lived in Marin, Lake, Sonoma and Solano Counties. The Wappo were the earliest known settlers in the valley they called talahalusi, or beautiful land.

Although we know them today as the Wappo, they historically referred to themselves by their tribelet names: Mishewal, Mutistul and Meyakama. Wappo may be an English corruption of the Spanish word guapo, or brave, presumably derived from their staunch opposition to Spanish invasion. They spoke a dialect of Yukian, one of the states oldest language families. Some of their terms influenced Spanish and American place names: the Mayacamas Mountains and Rancho Mallacomes (also called Rancho Muristul y Plan de Aqua Caliente) come from the Meyakama (water going out place) and Mutistul tribelets, Rancho Caymus from the Kaimus village and Sonoma from the ending phrase -tso nma, meaning campsite.

Within the tribelets were villages and campsites with a variety of structures made of thatched grass. Each had at least one sweathouse. Villages were headed by a chief, a person of any gender who was appointed for life. Wappo chiefs supervised ceremonies, resolved intra- and intertribal conflicts and directed hunting and fishing expeditions.

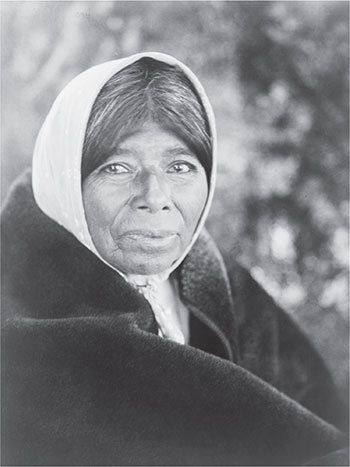

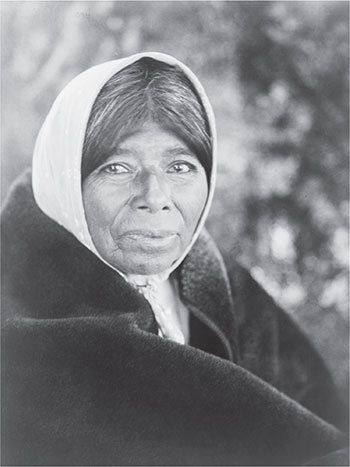

An unidentified Wappo woman photographed around 1924 by Edward S. Curtis. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

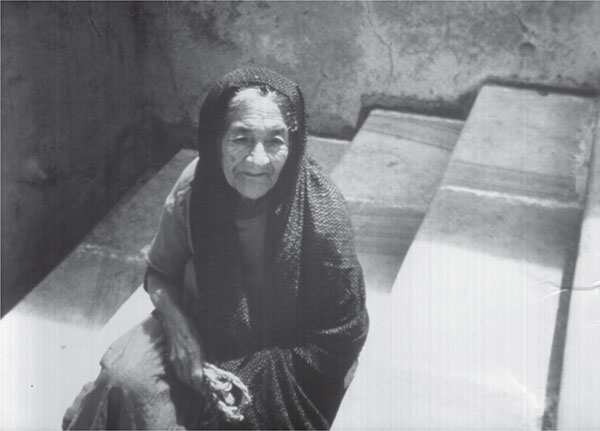

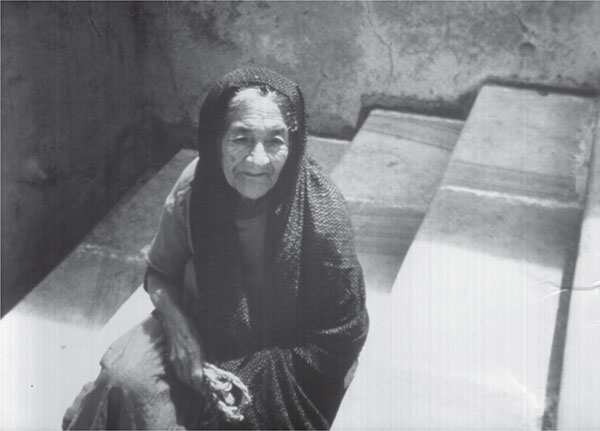

An undated photo of an unidentified Wappo woman.

Next page