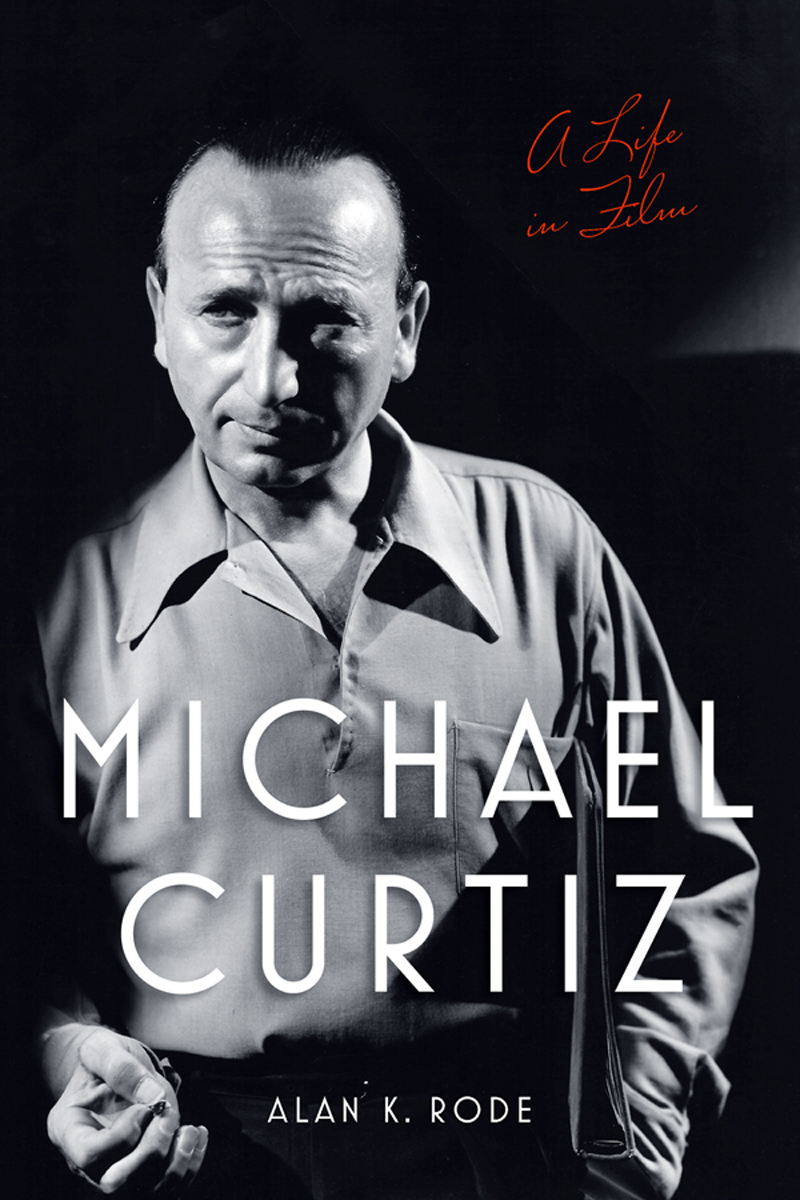

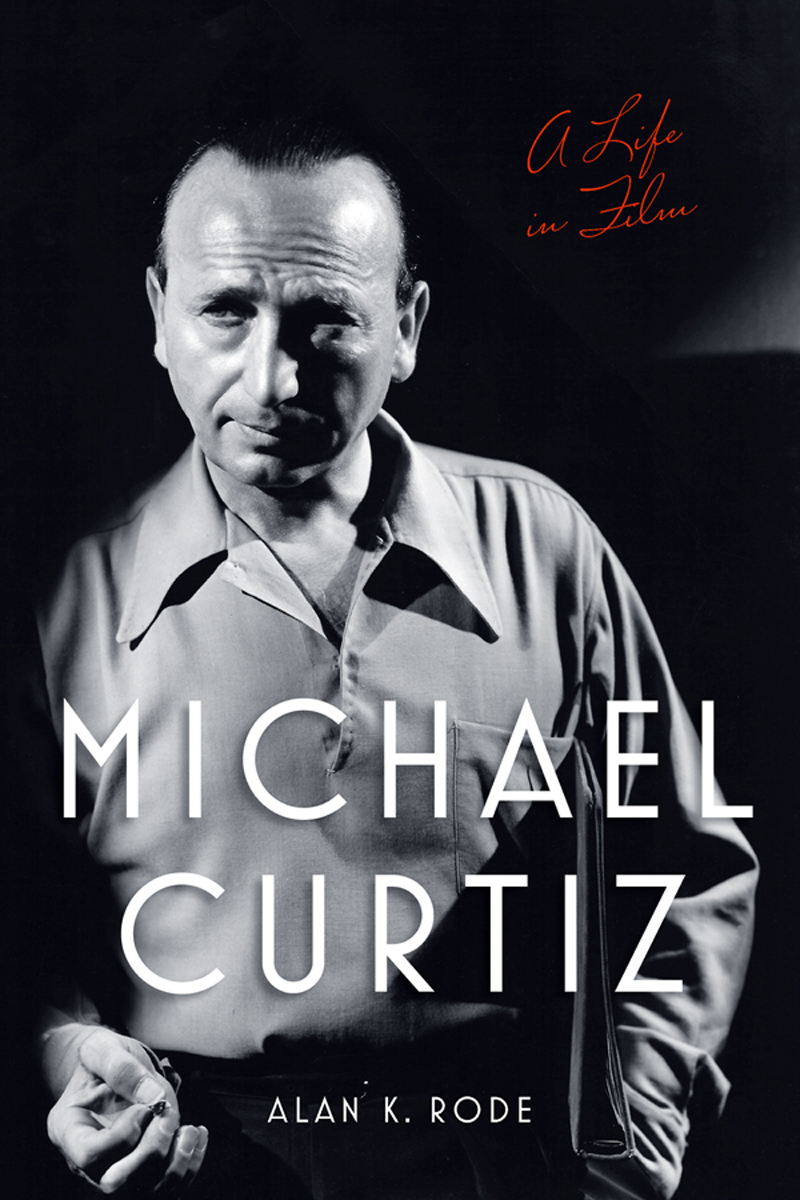

MICHAEL CURTIZ

MICHAEL CURTIZ

A Life in Film

ALAN K. RODE

Copyright 2017 by Alan K. Rode

Published by the University Press of Kentucky,

scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rode, Alan K., 1954 author.

Title: Michael Curtiz : a life in film / Alan K. Rode.

Description: | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017029778| ISBN 9780813173917 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813173979 (pdf) | ISBN 9780813173962 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Curtiz, Michael, 18881962. | Motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.C87 R65 2017 | DDC 791.4302/32092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017029778

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

For Mom,

who first told me about Hollywood

Contents

Prologue

People began queuing up on Thursday afternoon, March 2, 1944, to secure a bleacher seat on Hollywood Boulevard for the sixteenth annual Academy Awards. Although the banquet to bestow the coveted statuettes had become an increasingly popular event, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had never produced anything on the scale of this evenings opus.

The local police couldnt handle the mass of fandom and photographers that spilled out in front of Graumans Chinese Theatre. Louis B. Mayer, Hollywoods top mogul, donated the services of his studio police chief, Whitney Hendry, along with a contingent of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cops to provide crowd control.

Accustomed to the mundane routine of waving Mickey Rooneys convertible through the front gate at Culver City, MGMs finest couldnt distinguish some of the Hollywood luminaries from the surging hoi polloi. The resultant heavy-handed treatment didnt go over well. Variety reported the following day that many of the stars found themselves pushed around by minions of the law and expressed their chagrin. Adding to the general confusion was the fact that no one had thought to assign valets to whisk away the long line of cars disgorging movie royalty curbside. George Jessel, Americas toastmaster, nervously worked the red carpet amid a gaggle of late-arriving movie stars, including Humphrey Bogart and his wife, Mayo Methot, who struggled through the crush to enter the theater by the 8:00 p.m. start time.

What had been a self-congratulatory gathering for industry elites in the swank environs of the Ambassador or Biltmore hotels was being reinvented this night as the premier public event of the motion picture industry at Sid Graumans 2,200-seat movie palace in the heart of Hollywood. With the wars outcome still in doubt, the sixteenth Academy Awards discarded the insular dining format for a ceremonial spectacle dedicated to the U.S. military.

The 1944 Academy Awards program opened with a U.S. Armyproduced short film saluting Hollywoods mobilization to support the war. Susanna Foster, the star of Universals 1943 version of Phantom of the Opera, sang the national anthem. The audience was thick with uniforms: Colonel and Mrs. Frank Capra, Colonel and Mrs. Darryl Zanuck, Captain and Mrs. Ronald Reagan, and so on, along with lesser mortals from all branches of the services. Jack Benny would host the second part of the ceremonyI am here through the courtesy of Bob Hopes having a bad coldon a worldwide shortwave radio hookup broadcast to the U.S. Armed Forces. The Academys president, Walter Wanger, intoned in the program: The motion picture industry places above all other considerations service to our nation.

The nominated films in the different categories offered emblematic testimony to a world at war: In Which We Serve, Five Graves to Cairo, Destination Tokyo, Sahara, So Proudly We Hail, This Is the Army, Hangmen Also Die!, This Land Is Mine, Crash Dive, Stand By for Action, Commandos Strike at Dawn, Corvette-K225, and Bombardier, among others. Half of the ten Best Picture nominees were associated with the ongoing conflict; studio insiders and local bookies piled change on either Casablanca or the distinctly non-war-themed Song of Bernadette for Best Picture.

The evenings program picked up momentum after a series of technical awards were acknowledged by polite applause and brief expressions of gratitude by the winners. Greer Garsons embarrassing five-minute monologue after receiving the Best Actress Oscar for Mrs. Miniver the previous year eliminated any possibility of stem-winder acceptance speeches by tonights winners. The director Mark Sandrich was tapped to present for Best Director. The nominees included some of the top film directors in Hollywood: Ernst Lubitsch for Heaven Can Wait, George Stevens for The More the Merrier, Henry King, the favorite for The Song of Bernadette, Clarence Brown for The Human Comedy, and Michael Curtiz for Casablanca.

Seated with the Warner Bros. contingent, Michael Curtiz appeared resigned to his fate. Even though his wife, Bess Meredyth, a charter member of the Academy, told him that tonight would finally be his turn, the veteran director believed he was snakebit when it came to the Oscars. Nominated as a write-in candidate for Captain Blood (1935), splitting the vote with Four Daughters and Angels with Dirty Faces (both 1938), and then narrowly missing with Yankee Doodle Dandy the previous year, Curtiz had never been recognized as Best Director. He reputedly summarized the dilemma in his mangled Hungarian-Anglo diction that made him the butt of countless jokes: Always the bridesmaid and never the Mother.

Fatalism leavened by humor was Curtizs cultural inheritance from his Magyar forebears. Throughout its long history, Hungary had endured an untold number of conquerors and privations, most recently being torn apart after World War I. The country also produced some of the twentieth centurys most talented people, many of whom ended up in the movie business. An apocryphal anecdote recalled a sign posted on a Hollywood studio soundstage during the 1940s: Its not enough to be Hungarian to make films. One must also have talent. Michael Curtiz assuredly met both these criteria. Though he realized that it was the work, not awards, that mattered, the lack of an Academy Award still rankled.

There had been the marginal recognition of his 1940 Oscar-winning short film

Next page