Table of Contents

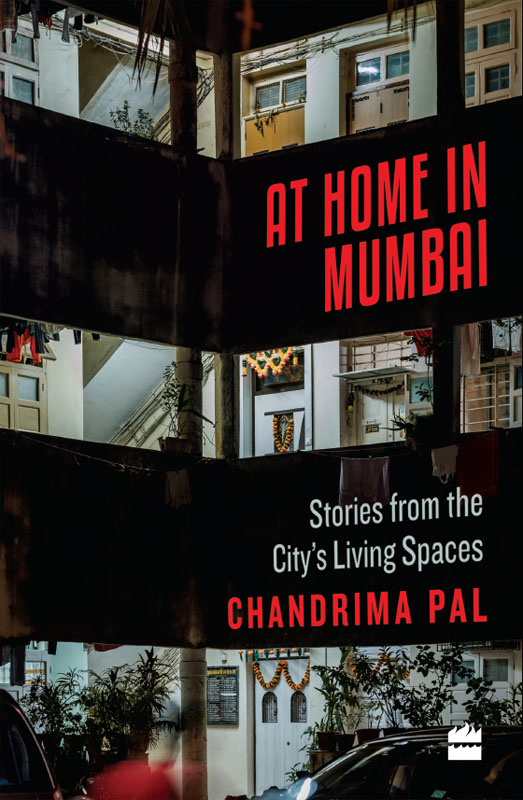

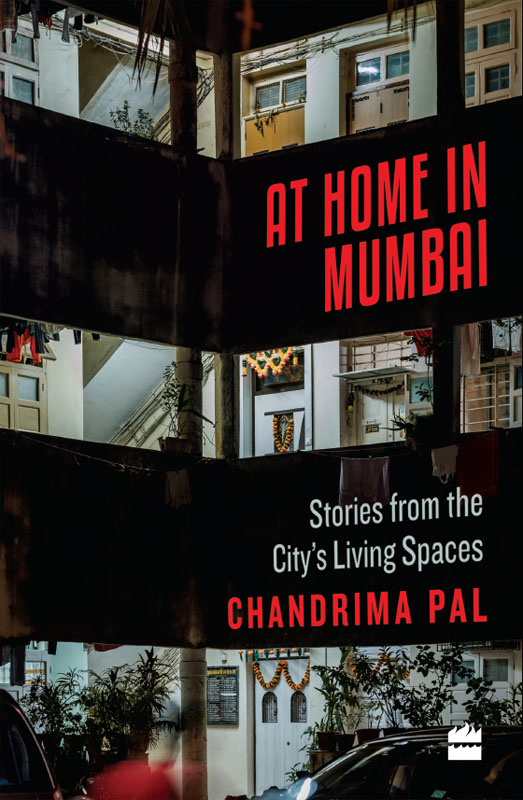

AT HOME IN MUMBAI

Stories from the Citys Living Spaces

CHANDRIMA PAL

To my family

Introduction

Everyone Has a Bombay Story

T HIS book happened over four years, many conversations, some memorable meals, long walks, a few rides and countless cups of tea and coffee. I am thankful to the strangers and friends who trusted me enough to share their stories with me. All of them appear as who they are, except one family that did not wish to be identified. I respect that.

My years in Mumbai were all about getting to know people and their remarkable personal journeys colleagues, neighbours, stars, auto-wallahs, cabbies, housekeepers and homemakers. What began as a weekend project to string these stories together, soon turned into an obsession with the subtexts and understories. This book is that master key which took me through more doors, towards more stories and a deeper understanding of the relationship between the houses and the people who make them, live in them and long for them.

I have tried my best to be faithful to the facts and have also relied on some previously published material. Sometimes, I have simply gone with the flow of the personal, more human narrative, where statistics and geography, politics or a public history may appear insignificant.

I have not tried to be politically correct, but have made a humble attempt to curate those stories that seem to say something different about being at home in Mumbai.

M INE started a day in December 2004, when I sat in a Premier Padmini cab, three bulging suitcases tied with a blue rope to its roof. We had left behind a troubled history in the unyielding city that was Delhi, sold off our nine-month-old flat, our second-hand Maruti 800 DX and all the furniture bought from Panchkuias bargain stalls, to give ourselves a second chance. It seemed most appropriate to do it here in Mumbai, where we could be anonymous and as ridiculously optimistic as everyone else.

My husband had disappeared into the innards of a skinny alley somewhere on Yari Road, Versova. Our landlord, an elderly Muslim gent who resembled the affable actor A.K. Hangal, was supposed to hand over the keys to our flat. It was a hot and sunny day. Traces of the Delhi winter lingered in my clothes, even as Mumbai worked its way under my skin and oozed from my pores. The osmosis had begun.

I waited in the grimy, noisy car, taking in bits of the sea that shimmered between the low houses and cottages-turned-shops and cafes. I tried to ignore the stench of fish hung up to dry. I waited for the keys to our new life, new story, with a book my husband had gifted me at the airport where he had come to meet me. You will need this, he had said, as I unwrapped a copy of Suketu Mehtas Maximum City.

Twenty minutes later, a noisy elevator carried us up to the fifth floor of our new apartment complex, our first address in the city. My husband pried the gates open: Mumbai elevators can be notoriously stubborn, noisy, intimidating. They speak the language of the housing society managers and chairpersons who sit in judgement over whether you are worthy enough to rent or buy your own place in their prized complex. I hesitated to step out, thinking we had arrived at the wrong floor. Because all I could see in front of me was a wall. A solid, whitewashed wall. We stepped out and turned right. There was a freshly painted white door. And it opened to yet another corridor. From the entrance, where I stood, I could see another wall the flat ended before it could even begin. I was Alice falling through the Rabbit Hole and waking up a size too big in a world too small. I would have died of claustrophobia, had it not been for the windows. Those gorgeous, sumptuous windows that opened to the sea. I had found my wonderland.

Our new home was everything a suburban Mumbai flat could be. Compact, ill-planned and inexplicably inviting. It was by far the smallest and most expensive home we had lived in. And over the years, it would be the most charming space we would ever inhabit. Because Shakti, B-504, Kalyan Complex overlooking a crematorium, a burial ground and a sanatorium, and which offered a view of the ocean and a garden, a glimpse of Madh Island, and from where every night you could see fishing boats bobbing on the dark sea was more than a physical place. It was a portal to a world that we would engage with for a decade, and yet it would always remain a chimera. Our neighbours were film stars and producers, models and choreographers. Sometimes we ran into them. At others, they left behind a whiff of their French perfumes in the elevator. Occasionally, one of them would drop all pretences and hurl full-bodied cuss words at a security guard or a driver or someone who may have failed to deliver whatever had been demanded of him. We lived in the heart of what you could say was the new tinsel town. Where coffee shops brimmed with aspiration and hope was a cookie that often crumbled. And we soaked it all in.

My love affair with Bombay began here, from Yari Road, in that cramped apartment that opened up my mind to the fantasy that was the city. It was crowded. It was boundless. It was teeming with strangers. And yet you would never feel out of place.

Two years later, I read and fell in love with another book that would reinforce my obsession with the city and the way it defined my concept of space physical and otherwise. Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts. If Maximum City took a dispassionate, journalistic look at the citys relationship with itself, Shantaram romanticized it in the voice of an adventurer. As a journalist, I had the opportunity of walking through the streets of Colaba with Roberts, who took me around the places that have been immortalized and touristyfied in his book. Places that inspired him to embrace the Bambaiyya life, the Bambaiyya way of looking at love, life and loss. With an infectious Ho jayega, attitude. The tall, imposing Australian fugitive-turned-best-selling-author-turned-activist took me to the fishermens colony near The Taj, to the open-air gyms where men who lived off the mystique streets worked on their biceps. He took me to Leopold that was yet to be scarred by bullet wounds during the 26/11 attacks. And he gave me a first-hand feel of what it was like to be a foreigner who finds a place in the city.

Shantaram was such a Mumbai story! Of a world within worlds, of collision and coexistence. Slums and high-rises, power and surrender. The key, I have realized, to Roberts unrelenting love affair with the city was how he made peace with the physical spaces. And the insanitary and inhospitable conditions, the days on the run, wasted in opium dens and tortured in Arthur Road jail were just fantastic plot points in the epic adventure in the city he was top-lining. It is as if for every door that is shut on an outsider, there are a hazaar windows that open up. And for those who have lived here, called this their home, a sliver of a window that looks out to an ocean of endless possibilities whether it is the swathe of imperious skyscrapers shrouded in clouds of aspiration, or the Arabian Sea that touches distant shores or the dunes of blue tarpaulin stretched over cardboard boxes and rickety tenements is any day better than just a door.

My earliest memories of the city were formed during long vacations, when I visited my aunt and her family who lived in a beautiful apartment in Santa Cruz, in the western suburbs.