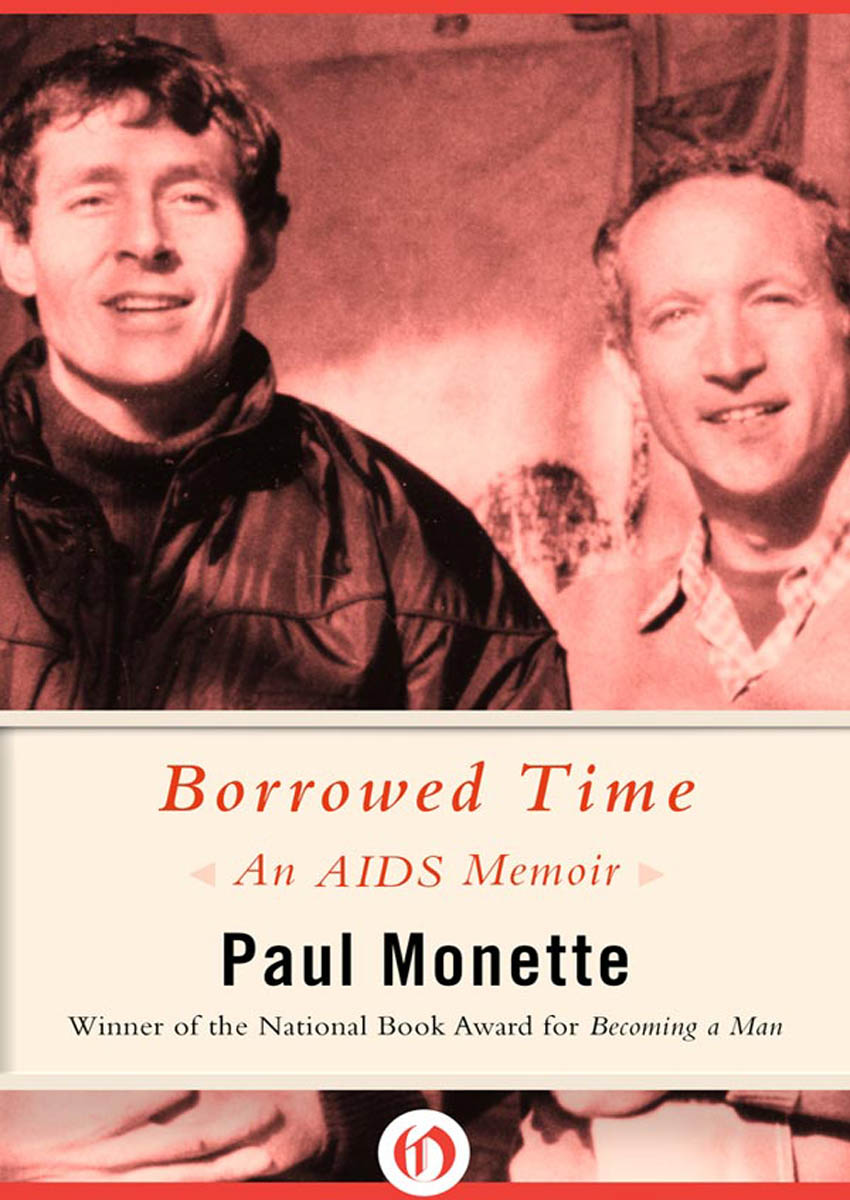

Paul Monette - Borrowed Time

Here you can read online Paul Monette - Borrowed Time full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Open Road Media, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Borrowed Time

- Author:

- Publisher:Open Road Media

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Borrowed Time: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Borrowed Time" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Borrowed Time — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Borrowed Time" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Borrowed Time

An AIDS Memoir

Paul Monette

TO DENNIS COPE

Unsung the noblest deed will die

Pindar, Fragment 120

Contents

I

I dont know if I will live to finish this. Doubtless theres a streak of self-importance in such an assertion, but whos counting? Maybe its just that Ive watched too many sicken in a month and die by Christmas; so that a fatal sort of realism comforts me more than magic. All I know is this: The virus ticks in me. And it doesnt care a whit about our categorieswhen is fullblown, whats AIDS-related, what is just sick and tired? No one has solved the puzzle of its timing. I take my drug from Tijuana twice a day. The very friends who tell me how vigorous I look, how well I seem, are the first to assure me of the imminent medical breakthrough. What they dont seem to understand is, I used up all my optimism keeping my friend alive. Now that hes gone, the cup of my own health is neither half full nor half empty. Just half.

Equally difficult, of course, is knowing where to start. The world around me is defined now by its endings and its closuresthe date on the grave that follows the hyphen.

Roger Horwitz, my beloved friend, died of complications of AIDS on October 22, 1986, nineteen months and ten days after his diagnosis. That is the only real date anymore, casting its ice shadow over all the secular holidays lovers mark their calendars by. Until that long night in October, it didnt seem possible that any day could supplant the brute

equinox of March 12the day of Rogers diagnosis in 1985, the day we began to live on the moon.

The fact is, no one knows where to start with AIDS. Now, in the seventh year of the calamity, my friends in L.A. can hardly recall what it felt like any longer, the time before the sickness. Yet we all watched the toll mount in New York, then in San Francisco, for years before it ever touched us here. It comes like a slowly dawning horror. At first you are equipped with a hundred different amulets to keep it far away. Then someone you know goes into the hospital, and suddenly you are at high noon in full battle gear. They have neglected to tell you that you will be issued no weapons of any sort. So you cobble together a weapon out of anything that lies at hand, like a prisoner honing a spoon handle into a stiletto. You fight tough, you fight dirty, but you cannot fight dirtier than it.

I remember a Saturday in February 1982, driving Route 10

to Palm Springs with Roger to visit his parents for the weekend. While Roger drove, I read aloud an article from The Advocate: Is Sex Making Us Sick? There was the slightest edge of irony in the query, an urban cool that seems almost bucolic now in its innocence. But the article didnt mince words. It was the first in-depth reporting Id read that laid out the shadowy nonfacts of what till then had been the most fragmented of rumors. The first cases were reported to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) only six months before, but they werent in the newspapers, not in L.A. I note in my diary in December 81 ambiguous reports of a gay cancer, but I know I didnt have the slightest picture of the thing. Cancer of the what? I would have asked, if anyone had known anything.

I remember exactly what was going through my mind while I was reading, though I cant now recall the details of the piece. I was thinking: How is this not me? Trying to find a pattern I was exempt from. It was a brand of denial I would watch grow exponentially during the next few years, but at

the time I was simply relieved. Because the article appeared to be saying that there was a grim progression toward this undefined catastrophe, a set of preconditionschronic hepatitis, repeated bouts of syphilis, exotic parasites. No wonder my first baseline response was to feel safe. It was themby which I meant the fast-lane Fire Island crowd, the Sutro Baths, the world of High Eros.

Not us.

I grabbed for that relief because wed been through a rough patch the previous autumn. Till then Roger had always enjoyed a sort of no-nonsense good health: not an abuser of anything, with a constitutional aversion to hypochondria, and not wed to his mirror save for a minor alarm as to the growing dimensions of his bald spot. In the seven years wed been together I scarcely remember him having a cold or taking an aspirin. Yet in October 81 he had struggled with a peculiar bout of intestinal flu. Nothing special showed up in any of the blood tests, but over a period of weeks he experienced persistent symptoms that didnt neatly connect: pains in his legs, diarrhea, general malaise. I hadnt been feeling notably bad myself, but on the other hand I was a textbook hypochondriac, and I figured if Rog was harboring some kind of bug, so was I.

The two of us finally went to a gay doctor in the Valley for a further set of blood tests. Its a curious phenomenon among gay middle-class men that anything faintly venereal had better be taken to a doctor whos on the bus. Is it a sense of fellow feeling perhaps, or a way of avoiding embarrassment? Do we really believe that only a doctor whos our kind can heal us of the afflictions that attach somehow to our secret hearts? There is so much magic to medicine. Of course we didnt know then that those few physicians with a large gay clientele were about to be swamped beyond all capacity to cope.

The tests came back positive for amoebiasis. Roger and I began the highly toxic treatment to kill the amoeba,

involving two separate drugs and what seems in memory thirty pills a day for six weeks, till the middle of January. It was the first time Id ever experienced the phenomenon of the cure making you sicker. By the end of treatment we were both weak and had lost weight, and for a couple of months afterward were susceptible to colds and minor infections.

It was only after the treatment was over that a friend of ours, diagnosed with amoebas by the same doctor, took his slide to the lab at UCLA for a second opinion. And that was my first encounter with lab error. The doctor at UCLA explained that the slide had been misread; the squiggles that looked like amoebas were in fact benign. The doctor shook his head and grumbled about these guys who do their own lab work. Roger then retrieved his slide, took it over to UCLA and was told the same: no amoebas. We had just spent six weeks methodically ingesting poison for no reason at all.

So it wasnt the Advocate story that sent up the red flag for us. Wed been shaken by the amoeba business, and from that point on we operated at a new level of sexual caution.

What is now called safe sex did not use to be so clearly defined. The concept didnt exist. But it was quickly becoming apparent, even then, that we couldnt wait for somebody else to define the parameters. Thus every gay man I know has had to come to a point of personal definition by way of avoiding the chaos of sexually transmitted diseases, or STD as we call them in the trade. There was obviously no one moment of conscious decision, a bolt of clarity on the shimmering freeway west of San Bernardino, but I think of that day when I think of the sea change. The party was going to have to stop. The evidence was too ominous: We were making ourselves sick.

Not that Roger and I were the life of the party. Roger especially didnt march to the different drum of so many men, so little time, the motto and anthem of the sunstruck

summers of the mid-to-late seventies. Hed managed not to carry away from his adolescence the mark of too much repression, or indeed the yearning to make up for lost time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Borrowed Time»

Look at similar books to Borrowed Time. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Borrowed Time and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.