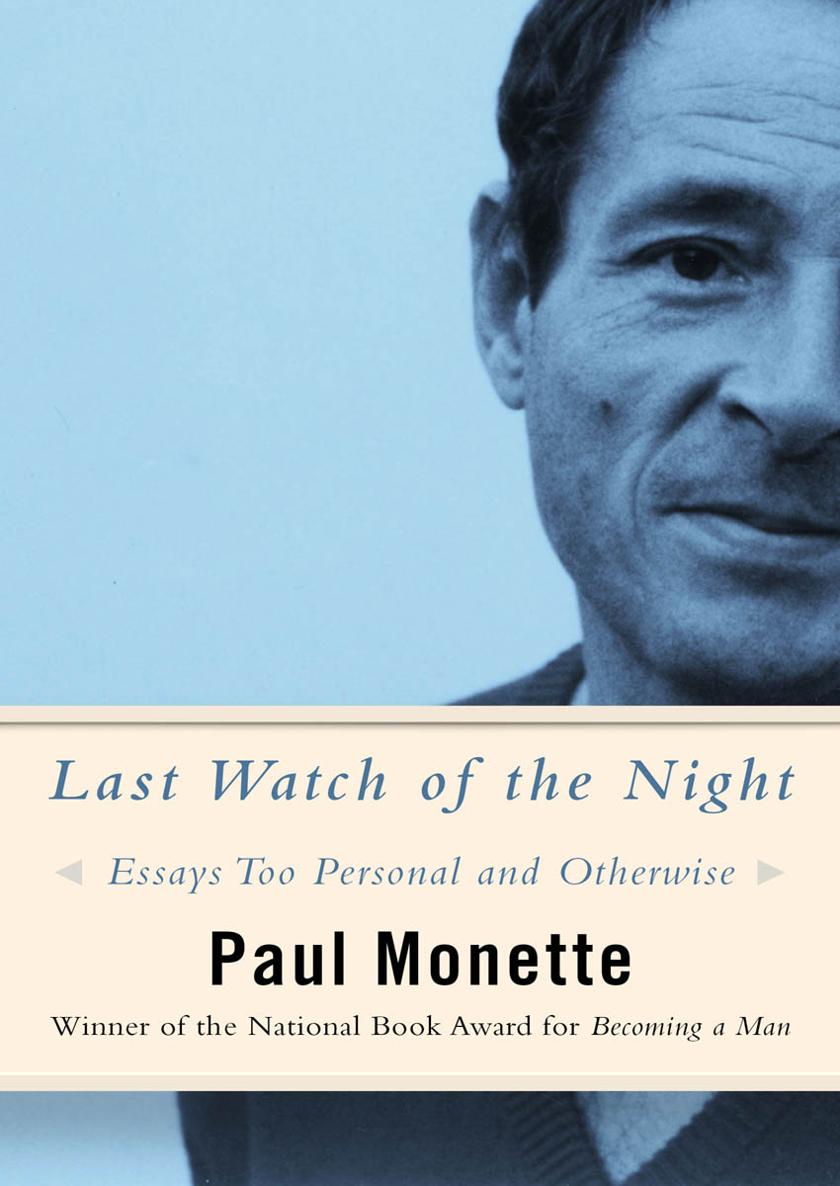

P UCK

S TEVIE HAD BEEN in the hospital for about a week and a half, diagnosed with PCP, his first full-blown infection. For some reason he wasnt responding to the standard medication, and his doctors had put him on some new exotic combination regimenone side effect of which was to turn his piss blue. He certainly didnt act or feel sick, except for a little breathlessness. He was still miles from the brink of death. Not even showing any sign of late-stage shriveling uplet alone the ravages of end-stage, where all thats left of life is sleep shot through with delirium.

Stevie was reading the paper, in a larky mood because hed just had a dose of Ativan. I was sitting by the window, doodling with a script that I had to finish quickly in order to keep my insurance. I miss Puck, he announced to no one in particular, no response required.

And I stopped writing and looked out the window at the heat-blistered parking lot, the miasma of low smog bleaching the hills in the distance. You think Pucks going to survive me?

Yup, he replied. Which startled me, a bristle of the old denial that none of us was going to die just yet. Even though we were all living our lives in dog years now, seven for every twelvemonth, I still couldnt feel my own death as a palpable thing. To have undertaken the fight as we had for better drugs and treatment, so that we had become a guerrilla tribe of amateur microbiologists, pharmacist/shamans, our own best healersthere were those of us whod convinced ourselves in 1990 that the dying was soon going to stop.

AIDS, you see, was on the verge of becoming a chronic manageable illness. That was our totem mantra after we buried the second wave, or was it the third? When I met Steve Kolzak on the Fourth of July in 88, he told me he had seven friends who were going to die in the next six monthsand they did. It was my job to persuade him that we could fall in love anyway, embracing between the bombs. And then we would pitch our tent in the chronic, manageable clearing, years and years given back to us by the galloping strides of science. No more afflicted than a diabetic, the daily insulin keeping him one step ahead of his body.

So dont tell me I had less time than a ten-year-old dogadmittedly one who was a specimen of roaring good health, still out chasing coyotes in the canyon every night, his watchmans bark at home sufficient to curdle the blood. But if I was angry at Stevie for saying so, I kept it to myself as the hospital stay dragged on. A week of treatment for PCP became two, and he found himself reaching more and more for the oxygen. Our determination, or mine at least, to see this bout as a minor inconvenience remained unshaken. Stevie upped his Ativan and mostly retained his playful demeanor, though woe to the nurse or technician who thought a stream of happy talk would get them through the holocaust. Stevies bark was as lethal as Pucks if you said the wrong thing.

And he didnt get better, either, because it wasnt pneumonia that was killing him. I woke up late on Friday, the fifteenth of September, to learn theyd moved him to intensive care, and I raced to the hospital to find him in a panic, fear glazing his flashing Irish eyes as he clutched the oxygen cup to his mouth. They pulled him through the crisis with steroids, but still wouldnt say what the problem was. Some nasty bug that a sewer of antibiotics hadnt completely arrested yet. But surely all it required was a little patience till one of these drugs kicked in.

His family arrived from back East, the two halves of the divorce. Yet it looked as if the emergency had passed, such is the false promise of massive steroids. I mean, he looked fine. He was impish and animated all through the weekend; it was we who had to be vigilant lest he get too tired. And I was so manically certain that hed pull through, I could hardly take it in at first when one of the docs, shifty-eyed, refined the diagnosis: Hes having a toxic reaction to the chemo.

The chemo? But how could that be? Theyd been treating his KS for sixteen months, till all the lesions were under control. Even the ones on his face: you had to know they were there to spot them, a scatter of faded purple under his beard. Besides, KS wasnt a sickness really, it was mostly just a nuisance. This was how deeply invested I was in denial, the 1990 edition. Since KS had never landed us in the hospital, it didnt count. And the chemo was the treatment, so how could it be life-threatening?

Easily, as it turned out. The milligram dosage of bleomycin, a biweekly drip in the doctors office, is cumulative. After a certain point you run the risk of toxicity, your lungs seizing with fibrous tissueall the resilience gone till you cant even whistle in the dark anymore. You choke to death the way Stevie did, gasping into the oxygen mask, a little less air with every breath.

Still, there were moments of respite, even on that last day. Im not dying, am I? he asked about noon, genuinely astonished. Finally his doctor came in and broke the news: the damage to the lungs was irreversible, and the most we could hope for was two or three weeks. Stevie nodded and pulled off the mask to speak. Listen, Im a greedy bastard, he declared wryly. Ill take what I can get. As I recall, the idea was to send him home in a wheelchair with an oxygen tank.

I cried when the doctor left, trying to tell him how terrible it was, though he knew it better than I. Yet he smiled and put out a hand to comfort me, reassuring me that he felt no panic. He was on so much medication for pain and anxiety that his own dying had become a moviea sad one to be sure, but the Ativan/Percodan cocktail was keeping the volume down. I kept saying how much I loved him, as if to store the feeling up for the empty days ahead. Was there anything I could do? Anything left unsaid?

He shook his head, that muzzy wistful smile. Then his eyebrows lifted in surprise: Im not going to see Puck again. No regret, just amazement. And then it was time to grab the mask once more, the narrowing tunnel of air, the morphine watch. Twelve hours later he was gone, for death was even greedier than he.

And I was a widower twice now. Nothing for it but to stumble through the week that followed, force-fed by all my anguished friends, pulling together a funeral at the Old North Church at Forest Lawn. A funeral whose orations smeared the blame like dogshit on the rotting churches of this dead Republic, the politicians who run the ovens and dance on our graves. In the limo that took us up the hill to the gravesite, Steves mother Dolores patted my knee and declared with a ribald trace of an Irish brogue: Thanks for not burning the flag.