TO ALL NEW FRIENDS,

TO WHOM I OWE MY LIFE IN FREEDOM

Contents

Guide

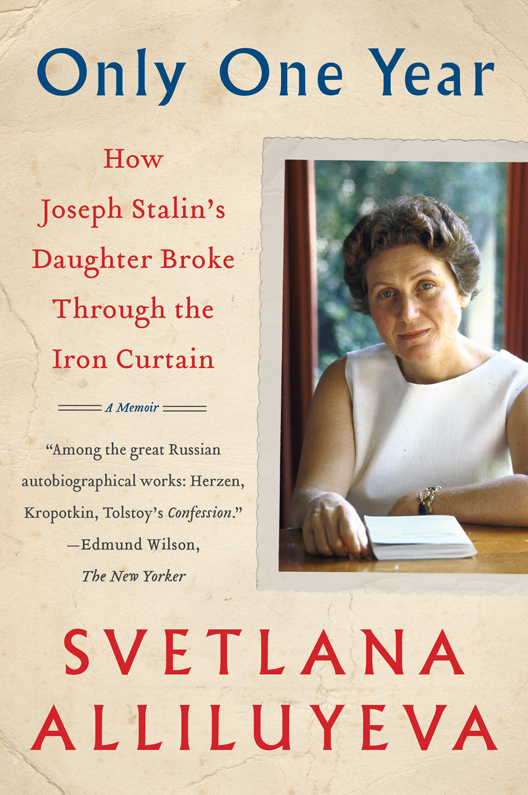

I T NEVER crossed my mind on December 19, 1966, that it was to be my last day in Moscow and in Russia. Still less could others around me have imagined anything of the kindmy son Joseph, his wife Helen, my daughter Katie, and many friends who dropped in that day.

A very cold daya frosty five degrees (Fahrenheit), reaching four below by nightfall. Snow kept falling, threatening to turn into a regular storm. My plane was due to leave the Sheremetyevo Airport at one oclock at night, but no matter how often I called the dispatchers office, no one there could tell me whether a flight would be possible in such weather. It seemed as if Moscow was determined not to let me go. Friends and acquaintances kept calling upIs it true? Are you really flying away today?and for the hundredth time I had to repeat the same thing. It was indeed extraordinary that I should have been given permission to take my late husbands ashes to India, and people just couldnt believe that I would actually leave that evening.

This was to be my first journey abroad, not counting the ten days during the summer of 1947 that I had spent with my brother in East Germany, where he was stationed at the time with an air corps. The whole thing seemed strange even to me, and although the permit had been granted a month before and I had had ample time to get ready for the trip, I still had not packed the big suitcase, borrowed from a friend, having no clear idea what Delhis climate was like and what I should take with me in the way of clothing. The second, smaller suitcase stood ready. It contained numerous presents for Indian relatives, without which, I had been told, I could not go; as well as presents from the Indian philologist, Dr. Bahri, to his family in Allahabad.

My greatest concern was an overnight bag into which I had put a smaller white bag containing a porcelain urn with the ashes. I had racked my brains for a long time, not knowing how to carry the urn. Much advice was given me, but there was only one thing I knew for certain: I must keep it near me, very close. It was something almost alive, which seemed very heavy to me. A sort of mysterious part of my own self.

My old school friend, Alya, had been with me since the morning. We had finished school together, and together had entered the university and had graduated from it, both of us majoring in the modern history of the United States. Even the choice of this subject was made for both of us, in part, by Alya, or rather by her mother, who had served for many years in the foreign department of Pravda as senior reader of reports from the United States. Alyas mother spoke English well, and had a sister who had been living for years in Detroit.

Alya was a quiet, blue-eyed girl, one of the top students both at school and at the university. She didnt know how to be angry or irritated, nor did she ever raise her voice. Yet she was firm about her principles, which were kindness, honesty, and work. And just like her were her three daughters, whose friend and pal she was, an equal among equals.

It was easy to talk to Alya about anything: she knew how to listen and always tried to understand. The only time she failed to understand me was when I told her that I had had myself baptized. She could understand my religious feelingshe had something of the kind, toobut she was distrustful of the Church as a social force.

Her whole family had known Brajesh Singh. Her daughter Tanya and her husband, a student of mathematics, had for several months occupied Singhs apartment, placed at his disposal by the publishers; he himself was then living with us. Alya knew many Indians in Moscowshe worked as an editor for the Publishers of Oriental Literature.

Now she had come to me, quiet and sweet as always, and we drank coffee in the kitchen, the chief room in my apartment, where our best friends were always entertained. On that day two other former schoolmates also dropped in to see meMisha and Vera.

Misha and I had been at school together since the age of eight. Like me he was redheaded, freckled, and read more than anyone else in the class. We used to discuss Jules Verne, Fenimore Cooper, and modern science fiction. At the age of eleven we became completely engrossed in Maupassantin both our homes there were large libraries. It was at this time, too, that we began writing notes to each other on blotting paperI love youand would then kiss on the rare occasions the opportunity to do so presented itself. But soon Mishas parents were arrested (they worked for the State Publishers), and later his aunt, a doctor of medicine, was sent to prison, too. My governess insisted that Misha be transferred to another class, having presented the schools principal with the damning evidencethose love notes on blotting paper. Our friendship was cut short; we met only once again, briefly, during the war. But after the Twentieth Party Congress (at which Khrushchev denounced the cult of personality), Misha found my telephone number and called me up: he was anxious about me. I immediately recognized his voicewhile in school we had called each other up almost every dayand from then on we became friends once more. By now he was a construction engineer, although from childhood he had loved literature and the humanities and, as before, continued to read a great deal. Kind and considerate, he knew everything about his former classmates: who was working where, who had married, who had children. He managed not to lose sight of any of his old friends and had kept up close contacts with many. He used to come and see me about once every six months and we would discuss our problems as parents. His younger son, who sang all day long like a nightingale, he had sent to a music school, dreaming that someday he might become a second Caruso. His older daughter, pretty and high-strung, caused him some anxiety. She was finishing school and, quite unexpectedly, developed a great interest in the history of the Far East and India; so I gave her my favorite books about India: the Autobiography and The Discovery of India by Jawaharlal Nehru.

Vera I had known since my earliest childhood, as our mothers had been friends. They were also on friendly terms with Regina Glass, the gifted teacher; it was her educational ideas that were practiced in my home, and it was to her, in essence, that I owed my interesting early childhood. Regina Glass had been educated in Switzerland. In Russia she had worked with Shatsky. My mother, who had such faith in enlightenment, was greatly influenced by Regina, with whom no one else in our family had any rapport: Father could not stand her and her pedagogical tricks, and soon insisted that she no longer frequent our home. But in Veras family Regina was loved.

Vera, since way back when Mama was still alive, used to be brought to us at Zubalovoher family usually spent their summers in the country not far away. Sometimes my nurse would take me to see them, or we might meet in a fragrant pine grove nearby. Later, Vera studied with me in the same school and in the same class, but here each one of us, having different interests, found her own friends. Vera was a born naturalist and, after graduating from school, entered the Biology Faculty at the university. I, on the other hand, always loved literature and the humanities.

Not an easy life fell to Veras share, but then from childhood she had been trained to give all of herself to her work, to persevere and be selfless. She took up genetics with her usual dedication. But in 1949, when she was graduating and could have started some research work on her own, this science had been declared idealistic and was forbidden in the U.S.S.R. Vera, like many geneticists who did not wish to renounce their vocation, had to continue her researches under cover. At present the chromosome theory has been rehabilitated, so that, after all, those years of clandestine work were not wasted. Vera is now one of the leading geneticists in the country. When I was leaving, she was completing her thesis (by now, doubtless, she has become a Doctor of Biology).