CONTENTS

I put for a general inclination of all mankind a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death. And the cause of this is not always that a man hopes for a more intensive delight than he has already attained to, or that he cannot be content with a moderate power, but because he cannot assure the power and means to live well, which he hath present, without the acquisition of more.

Thomas Hobbes

AUTHORS NOTE

I T IS ALWAYS A BIT OF A GAMBLE TO ATTEMPT A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT of someone who is still alive and who, moreover, plays an active and prominent role in current affairs. The task is even trickier when your objective is neither to sing praise nor issue judgments, when you wish neither to sanctify nor condemnwhen you are not trying to turn your subject into the victim of your own premeditated, malicious intentions.

At the other end of the spectrum lies the illusion of objectivity. Thanks to Georg Lichtenberg, ever since the end of the eighteenth century, we have known that even impartiality is partial. It would be foolish of us to try to deceive our readers into thinking that as the authors of this book we have no opinion, that we feel an academic indifference for the character that has inspired these pages.

Our biography of Hugo Chvez represents an effort to contribute a certain amount of complexity to a process that many people seem determined to simplify. The polarization that the president of Venezuela generates, both in and out of Venezuela, reflects the complex and very broad range of feelings he tends to inspire in people. It is almost impossible to observe him without being affected by the strong sentiments of those who alternately idolize and demonize him.

We chose to assess this reality by writing the story of a mans life in the manner of journalists, basing our research on the testimonies of a number of people who have been at his side during different periods in his life. Some of these people have stood by him, whereas others have distanced themselves and now count themselves among the opposition. Through a labyrinth of different paths, this work also led us to a great deal of written material, including the presidents own personal diaries and a small sliver of correspondence from his early years. However, more than a linear narrative, this book offers something of a choral dynamic, a collective construction of the experience of Hugo Chvez Fras.

We would like express our gratitude to all the people we interviewed and who agreed to work with us, people who offered us both their time and their trust. We would like to thank the journalist Fabiola Zerpa, our assistant in this endeavor, whose contributions were invaluable. And Gloria Majella Bastidas and Ricardo Cayuela, always precise and lucid in their reading and comments.

Cristina Marcano

Alberto Barrera Tyszka

INTRODUCTION

by Moiss Nam

J ANETTA MORTON LIVES ABOUT A HALF HOUR AWAY FROM THE WHITE House. Not that she has ever been there. The unemployed single mother of two girls shares a small house with her sister in one of the poorest neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. Morton does not know much about Hugo Chvez. But for her, the Venezuelan president is a hero. I wish George W. Bush was like him, she says. Morton is one of the 1.2 million poor Americans who get discounted heating fuel for their homes from CITGO, an Oklahoma-based oil company owned by the Venezuelan government. She also got a glossy brochure explaining that this was just an act of basic human solidarity from a president that cares for the poor everywhere, not just in his native Venezuela. This is not about politics, the brochure said.

In South Africa, President Chvez also has admirers. In Soweto, a poor neighborhood in Johannesburg, political activists enthusiastically follow Chvezs Bolivarian Revolution, and some of them were invited to Venezuela to see it firsthand and even to meet with the president. They too say that they would like a leader like Hugo Chvez for their country. In Lebanon, some Hezbollah supporters have named their newborn sons Hugo.

Andres Oppenheimer, a syndicated columnist for The Miami Herald, traveled to India in January 2007 to interview business leaders, politicians, and others about that nations profound transformation. One of his stops offered quite a surprise. Reporting from New Delhi, Oppenheimer writes:

I happened to be giving a talk at the Jawaharlal Nehru University here the day that Venezuelan President Hugo Chvez announced the nationalization of key industries. I thought the news would help me make the case that Chvez is destroying Venezuelas economy. How wrong I was!

Far from applauding, the professors and students at the School of International Studiesa major recruiting ground for foreign service officialswere looking at me with a mixture of anthropological curiosity and disbelief. It was obvious that, for most of them, Chvez was a hero.

How many of you think Chvez is doing a lot of good for Venezuela? I asked my audience. Most of the students raised their hands.

Why do you think that? I asked. A doctoral student named Jagpal, who is doing his thesis on Venezuela, said that Chvez had put an end to a corrupt economic and political elite, and had focused the governments attention on the poor.

Janetta Morton, the Soweto activists, the Lebanese parents, and the Indian university students are only four examples of a rare and far wider phenomenon: a Latin American political leader who becomes a household name and a global icon.

It is a rare phenomenon because Hugo Chvez is the only Latin American politician in the past half century who has been able to acquire the type of worldwide name recognition and star power enjoyed by Ernesto Che Guevara and Fidel Castro.

How did this happen? How did a poor boy, born and raised in Sabaneta, a small city deep inside Los Llanos (the plains) of a country mostly known to the rest of the world for its oil and beauty queens, grow up to become almost as well known asand far more admired thanthe president of the United States? What does Hugo Chvez have that other leaders in Latin America or any other poor region in the world dont have?

The answers to these questions provide interesting clues not just about Chvez the man; they also reveal interesting trends in the politics and economics of the world in the early years of the twenty-first century.

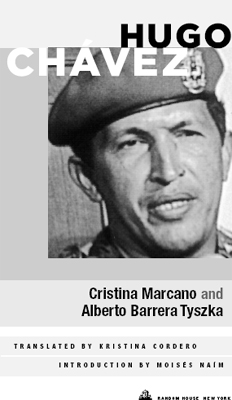

Of course, Hugo Chvezs personal history is the earliest source of hints about his surprising performance. And herein lies the importance of this biography by Cristina Marcano and Alberto Barrera Tyszka, two of Venezuelas best journalists, who produced this carefully reported and objective narrative of Chvezs life as he approached his fiftieth birthday. Marcano and Barrera eschew easy generalizations and facile conclusions about the nature of the man and his motives. They are careful not to rely on psychological speculations or pass political judgments about a man whose personal charisma and polarizing decisions have made it so hard for most commentators to retain objectivity and balance. But their dogged reporting and interviews with crucial individuals in Chvezs life do yield interesting insights about this perplexing, contradictory leader. Readers will find interesting links between his past and his present and perhaps even his future and that of his political career.

Personal histories, as we know, are shaped by the places and times in which they occur. In an increasingly connected and interdependent world, they are also shaped by what is going on elsewhere. And sometimes elsewhere can be very far away. Afghanistan, for example, is very far from Venezuela. So is Iraq. Yet Hugo Chvezs performance and possibilities are closely intertwined with events in these places located at Venezuelas antipodes or to the events in lower Manhattan on September 11, 2001. For many reasons unrelated to Chvez, he turned out to be one of the main beneficiaries of the terrorist attacks of 9/11 against the United States. Not that he had anything to do with the attacks. But partly as a consequence of 9/11, oil prices more than doubledand sent a tsunami of petrodollars to the coffers of the Venezuelan government.

Next page