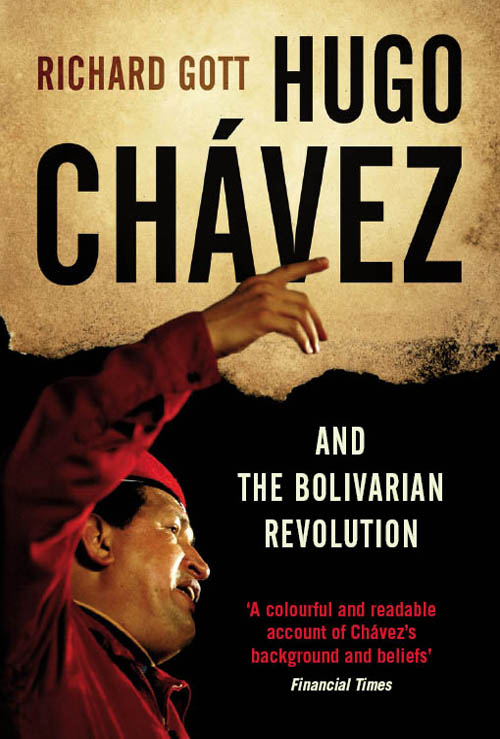

Hugo Chvez and the Bolivarian Revolution

Also by Richard Gott

The Appeasers (with Martin Gilbert), 1963

Guerrilla Movements in Latin America, 1971

Land Without Evil, Utopian Journeys across the

Latin American Watershed, 1991

Cuba, A New History, 2004

Hugo Chvez and the Bolivarian Revolution

RICHARD GOTT

With photographs by

GEORGES BARTOLI

First published by Verso in 2000 under the title

In the Shadow of the Liberator: Hugo Chvez and the Transformation of Venezuela

Republished under present title by Verso 2005

This new edition published by Verso 2011

Richard Gott 2011

Photographs Georges Bartoli

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eBook ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-802-0

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset by Hewer UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in Sweden by ScandBook AB

Once upon a time a traveller arrived in Caracas as night was falling, and, not pausing even to shake off the dust of the road, asked no, not where he could eat or sleep, but how he could get to the statue of Bolvar. They say that, alone beside the tall, fragrant trees of the square, the traveller stood in front of the statue as tears ran down his cheeks; the statue seemed to move, like a father when his son draws close to him. The traveller was right to do this, because all of us in the Americas should love Bolvar like a father Bolvar and all the others who fought as he did, so that the Americas would belong to their own people.

Jos Mart, La Edad de Oro, New York, 1889

CONTENTS

PART THREE: RECOVERING THE REVOLUTIONARY TRADITIONS OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

INTRODUCTION TO THE 2011 EDITION

Two hundred years ago, on 11 July 1811, a newly elected Congress in Caracas declared the Republic of Venezuela to be independent from the rule of Spain. Simn Bolvar, their principal spokesman, went on to wage a protracted war over the next thirteen years to drive the Spanish from other countries in Latin America from Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia culminating in the battle of Ayacucho in December 1824. This was an unprecedented struggle that changed the face of the continent.

Today, two centuries later, another Venezuelan leader has raised the Bolivarian flag, in a fresh attempt to liberate Latin America from alien rule, not from Spain but from the economic and cultural tentacles of the United States. Like his hero Bolvar, President Hugo Chvez is a military man, but he does not seek liberation through military conquest. He is a convinced democrat, hugely popular, whose long period in power (since first being elected in 1998) has been punctuated by regular elections, almost every year. His message of liberation, freedom, and revolutionary socialism is not spread at the point of a sword but leaps across frontiers and continents through the power of example.

Free elections in Latin America have often thrown up radical governments that Washington would like to see overthrown, and the Chvez government is no exception to this rule. Chvez is a genuinely revolutionary figure, one of those larger-than-life characters who surface from time to time in the history of Latin America and achieve power perhaps twice in a hundred years. A man of the left, he is like most Latin Americans with a sense of history distrustful of the United States. He wants to change the history of the continent, and he has spent the first decade of the twenty-first century doing just that.

The name Chvez summons up fear in the minds of the old conservative elites throughout Latin America and alarm in the corridors of Washington, but it produces great hope and excitement in the ranks of Latin Americas poor, the huge majority of the continents population. Chvez has also become popular in other parts of the world, notably in the Middle East, where his hostility to the foreign wars of the United States and his sympathy for the Palestinian cause has won him many supporters.

Radical, like-minded governments now rule in more than half a dozen countries in Latin America, inspired by the same Bolivarian rhetoric (even though some of them like Cuba, Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay lie outside the traditional orbit of Bolvars conquests). A recent film, South of the Border, directed by Oliver Stone, set out to interview many of these leftist presidents, revealing in dramatic form the extent of the revolutionary changes affecting the continent. Not since the time of Bolvar have so many countries begun to move forward together in a progressive direction. Earlier revolutions took place in Mexico, in Bolivia, in Cuba, in Nicaragua, but they occurred as single examples, never at the same time.

Five of these new radical presidents met at a public gathering in February 2009 in the Brazilian city of Belem, on the banks of the Amazon delta. They had come together at one of the Porto Alegre gatherings of the World Social Forum, which began in 2001 as an opposition event to the annual Davos meeting of the presidents and bankers of the capitalist world. The Social Forum had long taken pride in its status as a non-governmental movement, the expression of a civil society that could not imagine itself conquering the peaks of traditional political power. Yet the assembled presidents in Belem were united in expressing their gratitude to the continents social movements that had made their improbable political victories possible and had continued to sustain them. Chvez called it the most important event of the year.

President Lula of Brazil was the host of the gathering, and he abandoned his prepared script to condemn the irresponsibility of the rich countries of the capitalist world. The economic crisis affecting Latin America, he said, was not caused by the socialism of Chvez or by the struggles of Evo Morales, the president of Bolivia, but by the bankrupt policies and lack of financial control of wealthy states outside the continent. Lula had long been a regular and much soughtafter visitor to Davos, but this time he avoided the Swiss Alps to take up his position alongside Chvez as a leader of the progressive forces of Latin America. He reflected on the extraordinary changes taking place in Latin America, and he praised the way in which people had chosen suitable presidents to confront the crisis. We were not put here by the local elites or the Pentagon, Chvez added quickly, but by the people.

Lula looked back over the many years of dictatorship and torture on the continent, recalling how unimaginable it would once have been to have a trade unionist as president of Brazil, an Indian running Bolivia, a progressive soldier in Venezuela, a radical young economist in Ecuador, and a priest, advocate of liberation theology, as president of Paraguay. He pointed out that the five presidents in attendance might have easily been joined by others. Tabar Vsquez of Uruguay, Michelle Bachelet of Chile, and Cristina Fernndez de Kirchner of Argentina had all been invited. He also referred to the significant political changes in North America: Who would have imagined, forty years after the murder of Martin Luther King, that a black man would be the president of the United States?