Copyright 2010 by Rafael Uzcategui. All rights reserved.

For information contact:

See Sharp Press

P.O. Box 1731

Tucson, AZ 85702

www.seesharppress.com

Uzcategui, Rafael.

Venezuela : revolution as spectecale / by Rafael Uzcategui ; Introduction, by Octavio Alberola ; translated by Charles Bufe.- Tucson, Ariz.: See

Sharp Press, 2010.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-884365-77-9 9781884365775

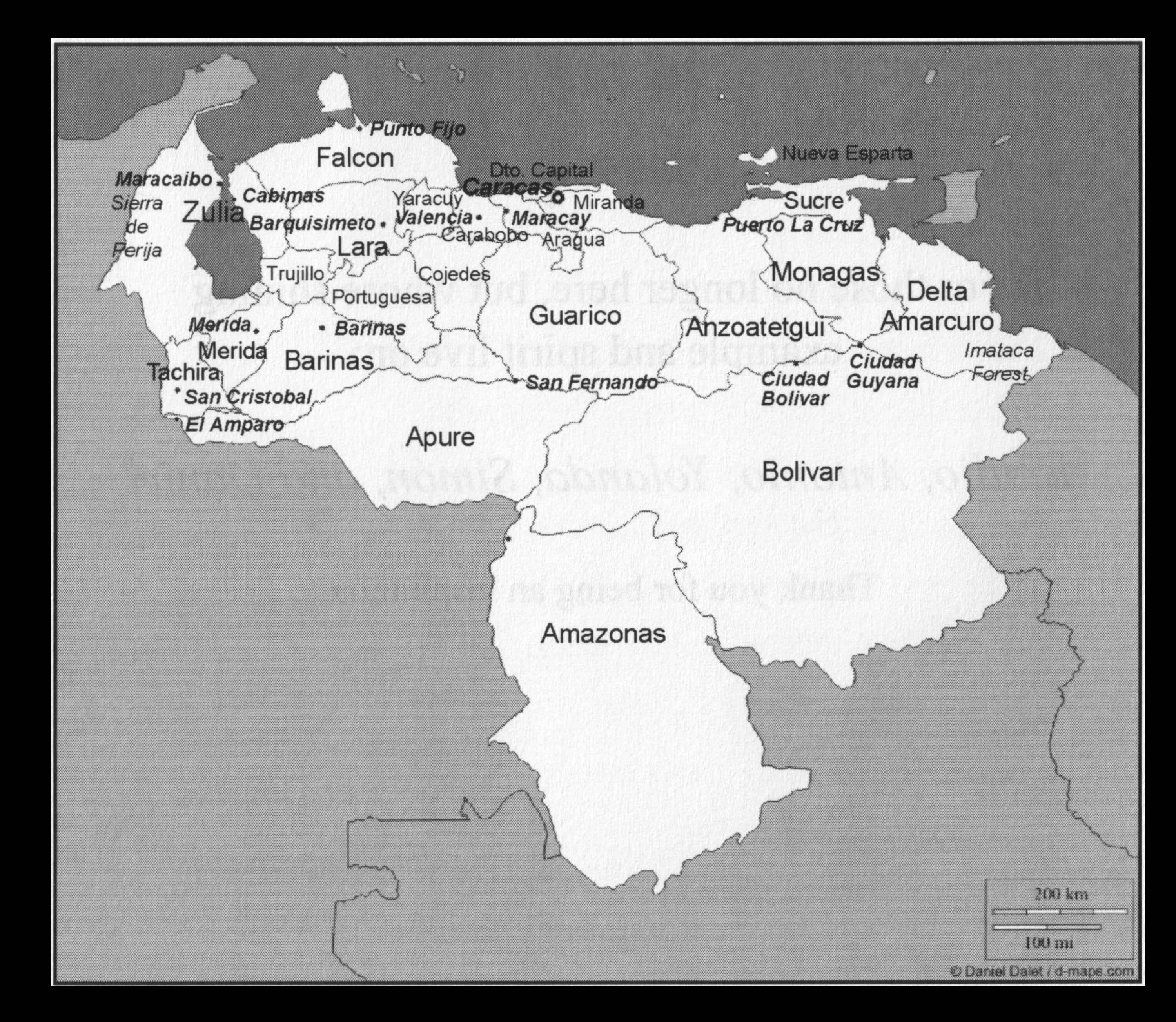

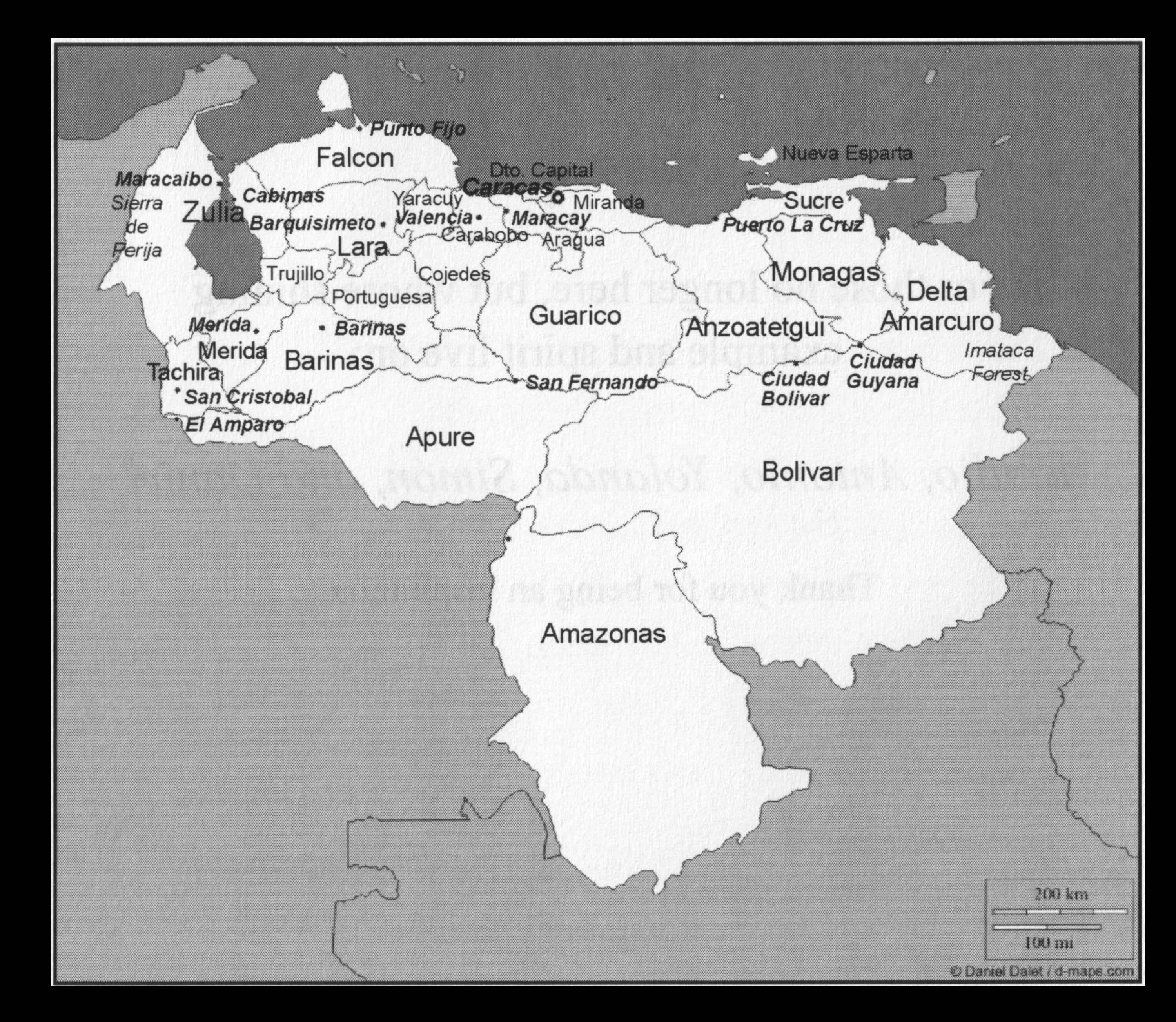

Contents: Map of Venezuela -- Introduction -- Preface -- Translators Note -Chapter . The Challenge of the Future -- List of Acronyms that Appear in the Text . 1. Chavez Frias, Hugo. 2. Venezuela -- Politics and government -- 19993. Venezuela -- Economic conditions -- 21st century. 4. Petroleum industry and trade -- Political aspects. 5. Petroleum industry and trade -- Venezuela.

987.0642

C ONTENTS

For those no longer here, but whose shining

example and spirit live on:

Emilio, Antonio, Yolanda, Simn, and Daniel

Thank you for being an inspiration.

Outline map of Venezuelan states courtesy of d-maps.com

I NTRODUCTION

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the implosion of the Soviet Union and totalitarian socialismwhich up to that time had presented itself as the driving force of modern historypolitical bipolarity ended. The world was now unipolar, and some called it the end of history. Upon the ruins of the real socialism, capitalism stood triumphant, and only bourgeois democracy remained as the paradigm of the social contract. [Who drafted and who signed this contract remains a mystery.tr.]

Class struggle continued, but now it did not have the goal of revolution but rather of electoral triumph. Both the left and the right assumed the victory of the capitalist system (the free market), and both made a tacit historic promise to compete for political power exclusively through universal suffrage as an expression of the will of the people.

As one consequence, during the two decades since the end of the Cold War, almost all of the dictatorial regimes have disappeared in Latin America. So, with the sole exception of Cuba, electoral democracy has become the means of political management of society, and the free market the means of economic management of society. From this grows the symbiosis between capitalist business and state funding, a symbiosis that grows ever stronger. And this does include Castros Cuba, that Cold War anachronism that demagogically tries to maintain the old political bipolarity.

So then its not strange that, from the arrival in power of Hugo Chvez and other populist Latin American leaders, weve seen the pretended renewal of the bipolar political struggle. Both the left and the right do everything possible to convince us of its existence, and to convince us that there is no alternative to it. But this time its presented as the irreconcilable political bipolarity of the new socialism (socialism of the 21st century) and imperialism.

This is a comprehensible coincidence of interests between those on both sides who aspire to govern. They reduce past and present history to this duality, because both left and right need to legitimize and justify their struggle for institutional control. But this is not comprehensible from the standpoint of those who continue to be the victims of exploitation and domination, given that the socialism of the 21st century, like real socialism, is simply a type of state capitalism.

Theres no doubt that the desire for guiding lights and certainty impels many leftists to seek refuge in any discourse that promises change, no matter how rhetorical and demagogic that discourse might be. This is particularly so when leftists have a follower mentality and understand neither whats happening around them (in China, for instance) nor recent history (that of the Soviet Union and other existing socialist countries, for instance). Given all this, its not surprising that new dreams of collective paradise have appeared, and that they assume the form of a revolutionary delirium with millenarian overtones. At present, these dreams center on Venezuela and, to a lesser extent, Bolivia. And these dreams uniformly have one truly revolting feature: fervid support for the regimes in power.

Neither is it surprising that the recipe of leftist populism has once more been found wanting, has once more demonstrated its incapacity to deliver on its emancipating promises. Instead, when one looks beyond the rhetoric and spectacle, one finds that the leftist regimes show their true face: authoritarianism and the cult of personality, with authority exercised at the convenience and desire of those holding the reins of government.

Springing from the failure of the neoliberal policies that the social democratic parties made their own, and with the advent of the anti-globalization movement of the 1990s, the new Latin American populism promised to reconstitute the social-welfare state and in the longer term to construct socialism compatible with representative democracy. This would all be done to cure the ills of unemployment and the precariousness of life and the misery that neoliberal economic policies had created or worsened.

This new populism reawakened the appetite for political struggle among the young, and also the old, who in many cases had begun to lose confidence in electoral games and institutional promises, and who rejected this dog-eat-dog world without understanding that there truly is another world possible. Those supporting the new populism believe that they can reach paradise through the new electoral radicalism.

But in the hour of truth, and as many of us have pointed out, this electoral alternative that pretends to be anti-capitalist, far from breaking with capitalism, instead adapts itself to the established order and submits to the imperatives of the market. In the process, it fails to fulfill its promises, or is incapable of doing so because of bureaucratic corruption. And it continues and amplifies the development policies that it had formerly called devastating, and which it had denounced for being in the hands of the transnational capitalists.

So, the alternatives have failed, not only because of not having known how to, or not wanting to, create a new form of political empowerment for the exploitedwhile exercising power in a near-authoritarian manner, and without opposition worthy of the namebut also because they are responsible for the continued devastation of the planet. As well, theyre also com-plicit in the destruction of the natural, social, and cultural environments of the indigenous communities to which they had promised the preservation of their lands and traditional ways of life.

This then is what the new populism has delivered. A populism that at times is xenophobic. A populism that pretends to be leftist, but that has contributed decisively to the disarming of the people and to the reintegration of the popular movements with the capitalist system of domination and exploitation. A populism that has almost annihilated the visions of authentic anti-capitalist alternatives.

All of this is put in concrete terms, with objective evidence, in this book. Even though the subtitle makes it clear that this is an anarchist critique of the Bolivarian government, this book is not an ideological analysis, but rather its the result of long and rigorous empirical investigationits filled with first-hand accounts and is also extremely well documented. And the references (documentation in the form of hundreds of endnotes) allows the reader to not only verify the information presented here, but to learn much more if he or she wishes.

Next page