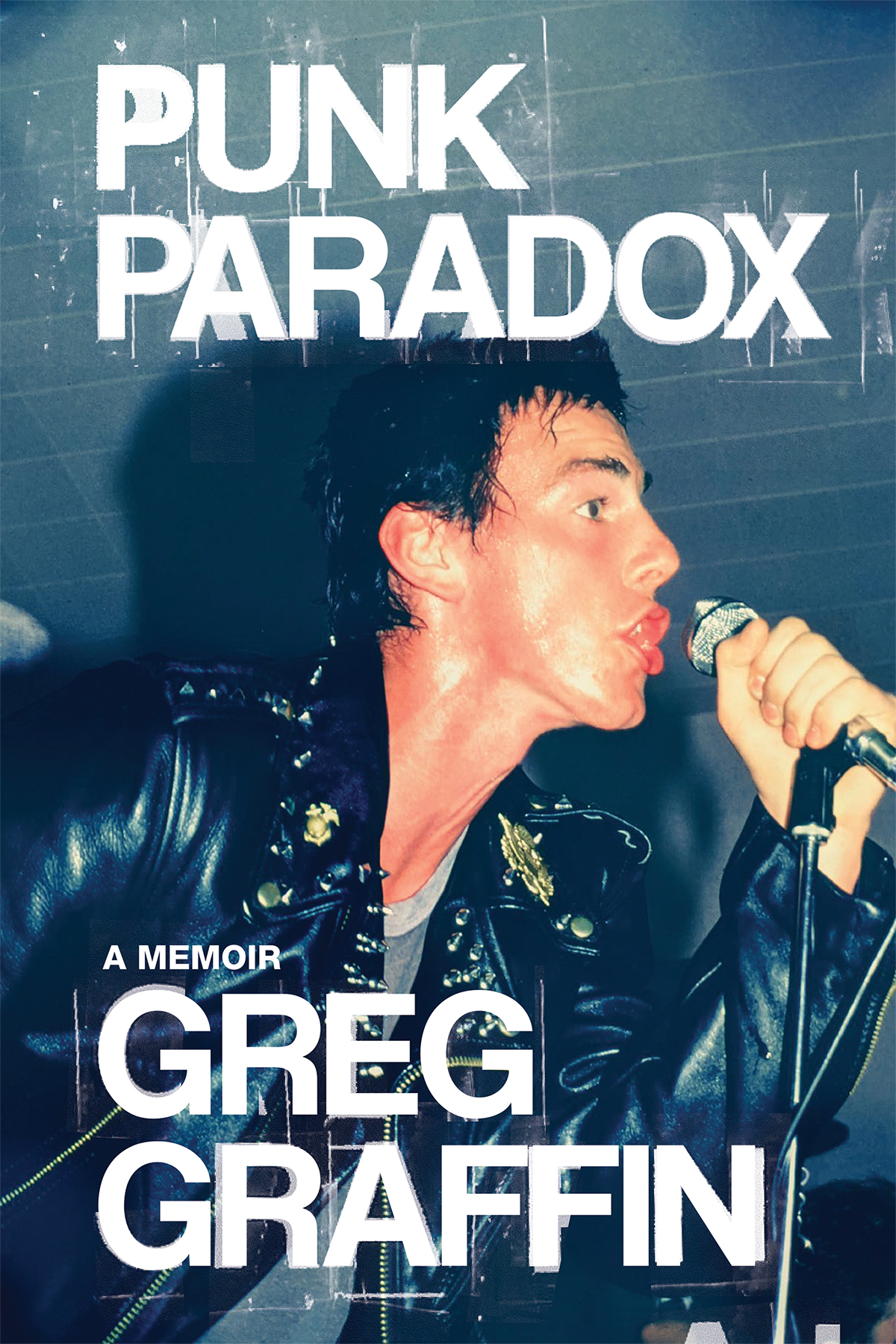

Copyright 2022 by Greg Graffin

Jacket design by Timothy ODonnell

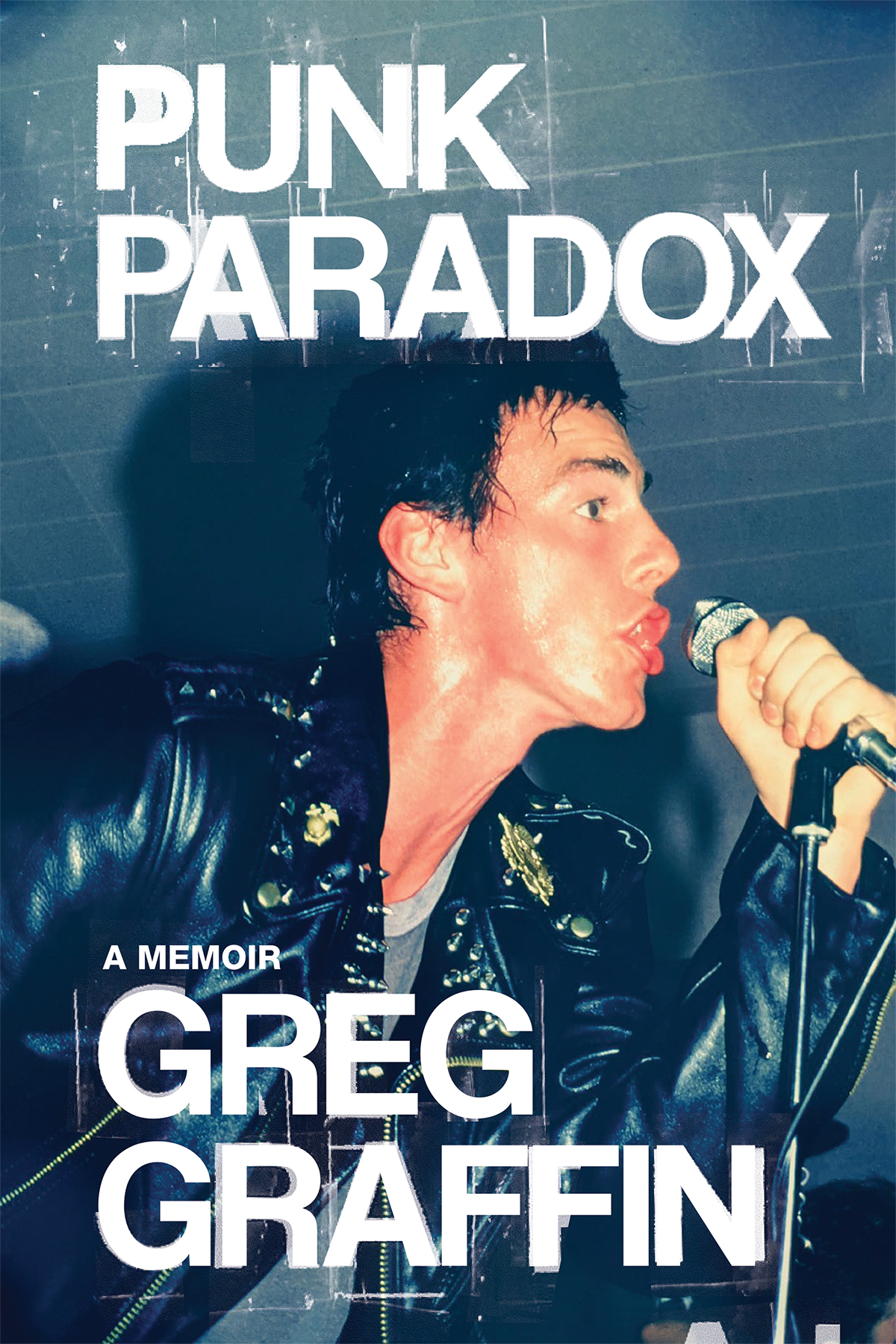

Jacket photograph by Brian Tucker (Fer Youz)

Jacket copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All photographs provided by the Graffin family archive unless otherwise noted.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

First Edition: November 2022

Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events.

To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022942474

ISBNs: 9780306924583 (hardcover); 9780306924606 (ebook)

E3-20220920-JV-NF-ORI

To all who hold dear

memories

of my mother, Marcella June Carpenter Graffin,

my father, Walter Ray Graffin,

and

of the events and friendships detailed on the following pages.

I told John go get gun. Graaaaagh, why did not John get gun?! George was looking at me with welts forming on his cheeks, grabbing for my lapel to bring my face closer to his as he searched for an answer, bewildered at his condition. Twenty people to jump on me, Grag, TWENTY PEOPLE TO JUMP ON ME! George trusted me. He and his cousin John, both Russian immigrants with buzz cuts, John, short and stocky with a massive unibrow, George, slender, of average height, a boxers head with chiseled cheekbones, were both punk rockers like me. They were a tandem pair. Whether cruising the streets looking for action or slam dancing at a gig, they were inseparable and spoke to each other in their mysterious foreign tongue. But they looked at me as the sensible kid from outside of Hollywood. Unimpaired by drugs or alcohol, I was, to them, the one who had an answer for everything.

I dont know why John didnt do what you wanted, George, but hes driving the truck now, hes right next to you, why dont you ask him yourself? But George was too pissed off, inebriated, and punch-drunk to be sensible at this moment. So he continued to harangue me. Grag, those mutherfuckers! Kick me, stump my body. Gun in glove box! Just keep driving, John, until you get George out of here, I said. No shit, Grraeg. Wot dee faahck! I keep driving all the way to Okee dogck, back to home ground, yew dough?

Even though I knew that George and John were likely packing heat somewhere in the vehicle, these guys werent hardened criminals and they sure as shit werent murdering types. They, like so many Los Angelinos, were first generation, blue-collar immigrants, whose families brought them there or shipped them off to work with cousins and extended families who settled in the Southland for the dream of a better life. They could be found every night outside any punk rock gig that was going on in the greater Hollywood region, looking for fun, girls, alcohol, or pills. They were just like all the other regulars of the scene at that time, in the fall of 1981. This night, however, was a slow night for punk gigs. No shows were going on in Hollywood or elsewhere, but as devotees of the punk lifestyle we had to hang out somewhere, and that meant the trusty safe haven of a hotdog stand on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood called Oki-Dog. Here, punk rockers were always welcomed. While every other fast-food hangout shunned us, the Oki-Dog proprietors greeted us with their Asian-accented hospitality: Haaaaay my freyend! What you have? Soggy french fries and chili dogs were the norm. But even if no food was purchased, they were ever tolerant of the chaotic punk antics in their parking lot each night. We felt accepted there, and we were always up for causing a stir nearby on the streets of Tinseltown or commencing an impromptu punk parade anywhere people might take notice. Lets head over to Westwood, said someone in the Oki-Dogs parking lot.

Westwood, with its glimmering wide sidewalks, glamorous movie houses, high-end restaurants, corner stores, donut stands, and fashionable clothing shops, was a melting pot of affluence, youth, and academic culture. Bordered by Wilshire Boulevard on the south and Hilgard on the east, its roughly twenty-four city blocks served the needs of many Los Angelinos. Across Le Conte Avenue sat UCLA. Just a few miles west down Wilshire was the beach. In the other direction was Hollywood and central Los Angeles. All roads led to Westwood, which had neither the dark-and-dirty sleaze of Hollywood, nor the crime and violence that characterized the rougher parts of LA since it served as the college town for UCLA students as well as the preferred site of weekly world premieres for the big film studios. Westwood saw its sidewalks thronged with the pulse of students mingling about with the multifarious citizenry from other neighborhoods who had come in to grab some of the gusto of its highly active nightlife. On the wide avenues were cruisers, guys and gals of various ethnicities that made car culture a way of life. Some of them, like the punk rockers I associated with, were out for disruption of Westwoods highfalutin, predictably upbeat evening tranquility, or worse, for violence.

I felt right at home in Westwood. UCLA was the reason the Graffin family moved to Los Angeles when I was only eleven years old. My mom had relocated from her job as an academic dean at University of WisconsinMilwaukee to take a deanship at UCLA in 1976. Occasionally she would take my brother, Grant, and me in to work and let us wander around on campus and into Westwood Village. This was no big deal. Even as little kids we roamed university campuses. Our dad too was a university man. He worked at the University of WisconsinParkside and some of my earliest memories are going to work with Mom or Dad and being told to get lost for a while as they tended to a meeting or taught a class. The unique smells of classrooms, libraries, mimeograph (xerox) rooms, and professors offices are some of my most deeply familiar, comforting associations. Nothing, however, felt comforting or familiar this night. As we piled out of cars at one of the university parking lots, it was clear that this handful of punk rockers were heading into a gauntlet of hostility in Westwoods festive environment. Tonight, we would be the entertainment.

I had been chauffeured that night by Greg Hetson, who was a notorious scenester, having played in two legendary bandsone, Redd Kross, no longer needing his services, and the other, Circle Jerks, already on top of the heap of LA bands, in the process of expanding their influence. Greg drove an El Camino and said: Hop in, Im heading home anyways. He lived not far from Westwood, and we hung out together at his apartment regularly, especially as a starting point for an evening of adventure. I jumped in Gregs passenger seat and stuck my head out the window as we cruised west on Santa Monica toward the intersection with Wilshire. Maybe well find some chicks in Westwood, said Greg, confident that, besides punk rock music itself, that was one topic that motivated the two Gregs equally.