For Nick and Olivia,

and the memory of Jock

Contents

Appendices

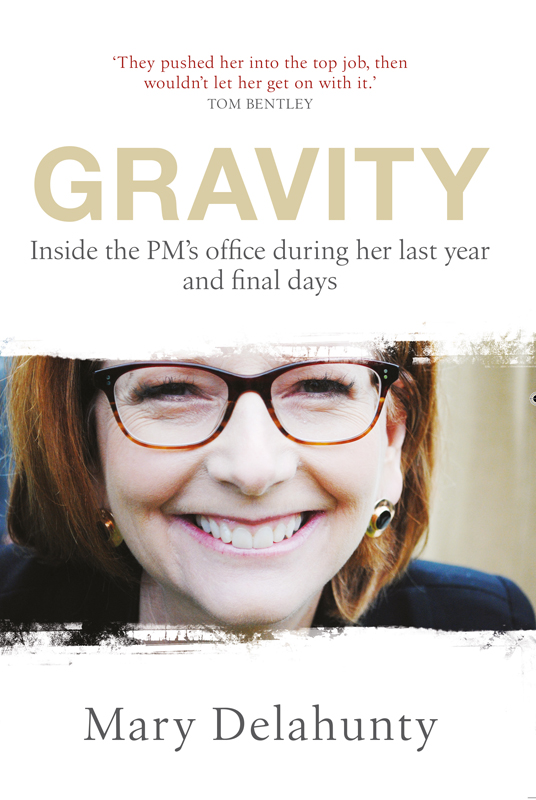

Julia Gillard sits calmly in a tub chair in her office, the milky winter sun cutting through the floor-to-ceiling grey curtains behind her. Until last night, she was Australias 27th prime minister; today, just fifteen hours after her caucus defeat, she is the member for Lalor, a backbencher preparing to leave parliament. Out we go with the boxes, she says drily, surveying her surrounds. The big desk, in front of which she famously welcomed Barack Obama, is marooned by boxes. The bookshelves are empty, cupboard doors spill open, and bouquets of fresh flowers with personal notes attached are gathering near the door. The Australian flag is still standing in its customary position in the corner.

During her election campaign in 2010, Gillard famously declared: Its time to make sure the real Julia is well and truly on display. Did you feel you could really be yourself as PM? I ask her now. She replies, You can be yourself, but always with a bit of padding on.

Julia Eileen Gillard needed more padding than most modern Australian prime ministers. For three years and three days she was pummelled with a nasty political trifecta, which compounded her leadership flaws and masked her leadership achievements. Gillard, as the first woman to win the office, drew a deep seam of personal viciousness not seen before in Australian public life. A messy campaign in 2010 yielded a minority government and the swirling negotiations infused the 43rd parliament. From the moment the ink was dry on her commission from the governor-general, she had to battle two political opponents. Tony Abbott, who from the outside lanced her leadership with the brand of liar, and Kevin Rudd, whose quest for revenge poisoned her from within her own party.

Are you angry about it? I ask.

Its a mix of a bit of anger and frustration, a little bit of relief.

She looks away. If we were having a red-hot go over policy, a real blue over policy like state aid or the uranium debate she begins before her voice trails off. In her fifteen years in the federal parliament and her long apprenticeship before, Julia Gillard was a political warrior and a policy pragmatist. She had been on the winning side of every Labor leadership manoeuvrethe victories of Beazley, Latham and Rudduntil yesterday.

I ask her about women in politics. Its still worth it, she insists. The political cauldron has extinguished several careers in the last twenty-four hours, including one of the most effective legislators and managers of government Australia has seen. And it has burned a good woman.

When she called the vote yesterday afternoon, Gillard insisted to the TV audience that leadership is about policy, not personality. But twenty-first-century politics, as former Treasurer Lindsay Tanner lamented in his book Sideshow: Dumbing Down Democracy has become an endless spin cycle of entertainment. While her opponents were performing for the cameras, Gillard was getting it done, pushing hundreds of pieces of legislation through the parliament.

Bells suddenly ring sharply. Have I got a pair? she asks her PA through the open door. The bells are calling members to a vote in the House. The parliaments work goes on relentlessly with the government still in minority and every vote is critical unless discounted with a pair from the Opposition. Julia Gillard is released from voting today as a small mark of respect for a fallen leader. The governmentsuntil last night Gillards governmentlegislation will be passed in the dying hours of the 43rd parliament.

The previous morning I was talking to Gillards chief of staff, Ben Hubbard, in his office. Gillard had popped her head around the corner of the concealed corridor between her inner office and his. She was wearing a casual cardigan, its sleeves rolled up, over a black dress. I stood up and greeted her. Good morning, Prime Minister. I hope you know how many women are behind you.

She looked almost surprised. I was referring clumsily to her support from women out there in the public, but her mind was here, in this place, deep in the moving intrigue of the parliamentary Labor caucus and her ebbing numbers. The prime minister refocused, responding quietly: I know.

She asked about Joan Kirner, who was recently diagnosed with cancer. At such a time of acute political danger, her concern for her friend and mentor was moving. Its a warmth that explains why so many who work closely with her love her. As well as that laugh, which she gives freely. Its somewhere between a giggle and a guffaw and it happens often. Though there was no laughing yesterday. As I left, her attention was back to the mountain she had to climbagain. Id been pressing for an interview. Hubbard shook his head. Weve cleared the diary. Shes ringing the colleagues.

So it was tight, very tight, and at that moment the contest hadnt formally been declared. It would be though, barely five hours later. Gillard herself threw the leader ship openagain. This time with the ultimatum that the loser vacate the field and leave parliament.

I walked towards the giant frame of Education Policy Advisor Tom Bentley in the warren of the prime ministers outer offices, known as the PMO, and congratulated him on the passing of the school funding Bill. Thanks. He grinned. Much later that night I saw him again slumped in his airless office. Our eyes met but we didnt speak. Five patient years of work, as Gillard described it, yet at the moment of triumph both Bentley and his boss were out of a job. Politics burns staffers and politicians alike.

And then the leadership struggle was on. The television monitors that inhabit every corner of the parliament were nearly in meltdown as both camps messed with each others minds over who was voting for whom. Emails came through to the PMs office on who was sticking with Julia.

Someone in the media office turned on gentle music. A guillotine blade hung above them, but those in the tumbrel were calm. Then there was a key ministerial defection. Policy staff groaned, Were fucked. A young female called Shame at the TV screen.

Warren Snowden, one of Gillards numbers men, left the back way. I noticed soulful music coming from a computer in the media office, a long-haired guitar strummer singing to the trees. Advisors congregated in their offices. There was nothing to say. By 7 pm, as the caucus filed in for the vote that would take down Australias first female prime minister, many were running on empty.

7.55 pm The caucuss returning officer confirmed a narrow 5745 return to Rudd.

8 pm Ben Hubbard called Julia Gillards staff to a meetinga terrible silence fell.

8.30 pm Someone turned the rugby league State of Origin on TV. Someone else found the whisky.

8.45 pm The PM and her thin Praetorian Guard of ministers and members walked the long beige corridor to her office. Gillards shoulders were upright, with only a quiver on her lip as she moved through her staff, who were lined up on both sides, applauding. It was the same ritual in March. Back then the walk from caucus carried a smile and a directive to go back to work. This time the defeated PM, grim and pale, sat in the honey-coloured tub chair and drafted notes for a resignation speech.

She has to keep it together until she sees the governorgeneral, former Attorney-General Nicola Roxon said to me as she hovered nearby. There were three Australian female firsts in this contextfirst female governor-general, first female prime minister and first female attorney-general. This government made history, briefly. Tonight only one was still on the throne and she had no real power.