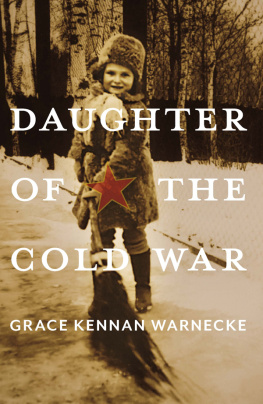

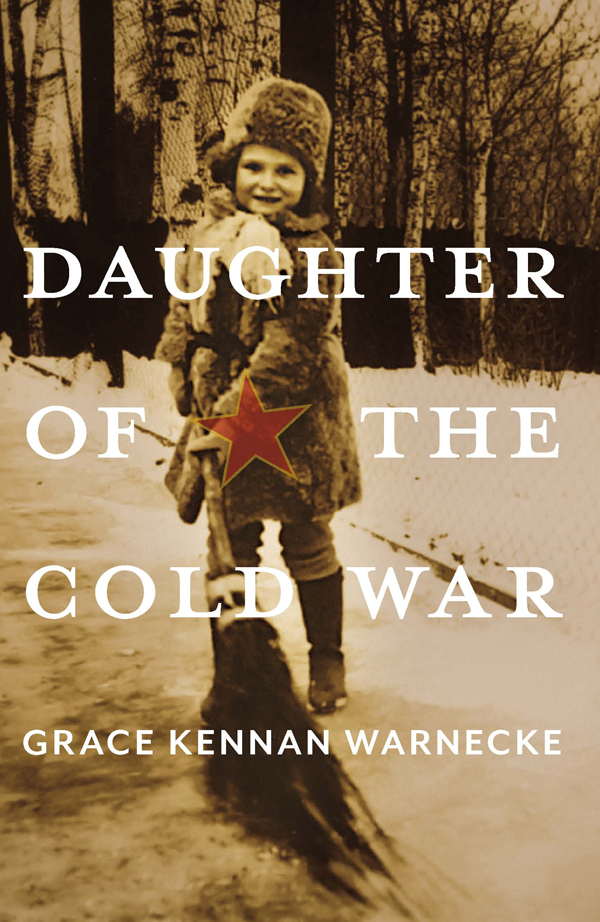

Jacket art: Grace in Moscow. Family photo.

Jacket design by Alex Wolfe

Acknowledgments

This book would never have been written without the help and encouragement of many people to whom I am deeply indebted.

Foremost was Veronica Golos, the writing teacher who started me on this path and from whom I learned so much. Equally important are the members of my writing group, Gerri Marielle, Mary Marks, Susan Ades Stone, and Rosanne Weston. We have been meeting for the past ten years, initially with Veronica and then on our own. Their intelligent critiques, support, and inspiration remain invaluable. Each has contributed in her own way, but I especially want to thank Susan for hours spent on editing and much needed tightening of the manuscript.

I am grateful to the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, which provided me with a fellowship and an office in which I could write, and to Blair Ruble and Joe Dresen at the Kennan Institute for their help.

My Russian chapters also benefited from the expertise of Nadezhda Azhgikina, Dick and Sharon Miles, Alan Cooperman, Martina Vandenberg, Viviane Mikhalkov, and the late Catharine Nepomnyashchy and Evgeny Porotov. Ukraine chapters were equally enhanced by the experiences and encouragement of Nell Connors, Marta Baziuk, and Susanne Jalbert.

Many thanks to my cousin, Elisabeth Eide, who corrected and enhanced the Norwegian chapters with her own vivid memories.

Professor Nancy Condee played a decisive role by her faith in my book and led me to Pittsburgh where I am happy to find myself in the expert hands of Peter Kracht at the University of Pittsburgh Press.

My close friends have supported, prodded, and kept me going, especially Laurence Eubank, Meredith Burch, Nancy Eddy, and two who are with us in memory only, Ken Regan and Anna Elman. They would have been so happy to see this book appear.

Thanks to Seth Farkas who was of invaluable assistance during the editing process.

Family, of course, plays a vital part of any memoir. I am particularly grateful to my siblings Joan, Christopher, and Wendy Kennan, my cousin, Eugene Hotchkiss, and my children, Charles, Adair, and Kevin who have put up with me and encouraged me all these years. While they did not want to be a major part of this book, they are always present.

PROLOGUE

An End and a Beginning

Feeling hundreds of eyes on my back, I walked slowly behind a priest carrying a towering and glinting cross up to the pulpit of the National Cathedral in Washington, DC. I was about to deliver a eulogy for my father, George F. Kennan, the diplomat and historian. Those are the titles that are etched into his granite tombstone, but to me he was much more than a prominent actor on the world stage. He was a guide, an icon, and a dominant force, and after days of apprehension about this moment, I felt suddenly calm and ready. To my mind, the cathedral seemed an especially appropriate venue for the memorial service. I had played in its crypts as a ten-year-old while boarding at the National Cathedral School for Girls and had knelt in those pews during many a long Sunday service. The majestic setting was familiar. My role was not.

All my life I had studied, admired, and loved my exceptional father, while occasionally being infuriated and deeply hurt by him. At times my great supporter, he could also be a cutting critic, and his disapproval was withering. He cast an enormousshadow, under which I was both nurtured and hidden. To escape, I ran head-on into some unfortunate relationships and periods of rudderless searching. Living my early years as the daughter of, I moved on to roles as the wife of, and eventually the mother of, as the people in my life never seemed to stray very far from the public eye. Finding a direction in life proved to be a challenge that spanned many decades and many continents.

What propelled me to get up and speak in front of all the distinguished gueststhe secretary of state Colin Powell, former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, Senators Biden and Lugar, countless ambassadors, governors, and public figures? I knew that Father would have wanted and expected my brother, Christopher, to represent the family, which he did, but would have been surprised by my participation. Once more, I was rebelling against Fathers old-fashioned discomfort with women assuming a public role. But I had to speak, both to honor my father and to acknowledge myself. The routes I had traveled led me very far afield, but now they were circling back, taking me up the long aisle of that familiar cathedral on a sun-warmed day in March 2005. At that moment I recognized myself as someone shaped by forces both ordinary and extraordinarya daughter with thoughts and feelings to share about a person who was as private as he was public.

I had struggled with the first draft of the eulogy. Writing and rewriting my tribute, trying to shed light on George Kennan as a father, Id also thought about myself. Sitting down after the eulogy and listening to the strains of Rachmaninoffs Vocalise, memories floated in, borne by the music. How much he would have loved this Russian musical send-off.

My fathers career in the Foreign Service molded my early life. I was born in Riga, Latvia, and journeyed with him and my mother to Moscow, Prague, Berlin, Vienna, and Lisbon. When his posts were deemed unsuitable for children, I was deposited with various relatives and in boarding school. It was my fatherwho decided that I would go to a Soviet school in war-torn Moscow, even though I knew no Russian. It was he who taught me to revere the power of the written word. He conveyed to me his love of Russia and Russian literature. But his legacy wasnt all formal lessons and books.

The oldest of four children born over a twenty-year span, I was lucky enough to be with my father when he was still young. He taught me skating in Vienna, read aloud to me by the hour, took my sister Joanie and me bicycling through Scotland, searching for our roots, taught me ballroom dancing in a small bedroom of a Scottish country inn. He left a legacy of insatiable curiosity about everything he saw. Every trip was full of adventures, and nothing we did was without a purpose. With our father as my guide, history was alive and I was part of it.

Years later, when he had already celebrated his hundredth birthday, I went to visit him. He was sitting, virtually immobile, in a wingback chair in his bedroom in Princeton, his long, sensitive fingers folding and unfolding a small napkin on the table in front of him. Sitting, facing him, heart thumping, I finally blurted out, Daddy, Im writing a memoira book about my life. To tell this to him, who had a two-volume memoir among his twenty-one published books, who had received the Pulitzer Prize twice, the National Book Award, the Bancroft Prize, and the Francis Parkman Prize for his writings, seemed an audacious step. He stared at me for a long time with no expression and then answered, Well, you could.

CHAPTER 1

A Nomad from the Start