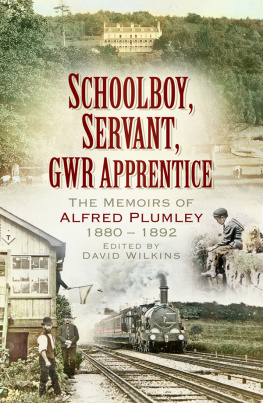

SCHOOLBOY,

SERVANT,

GWR APPRENTICE

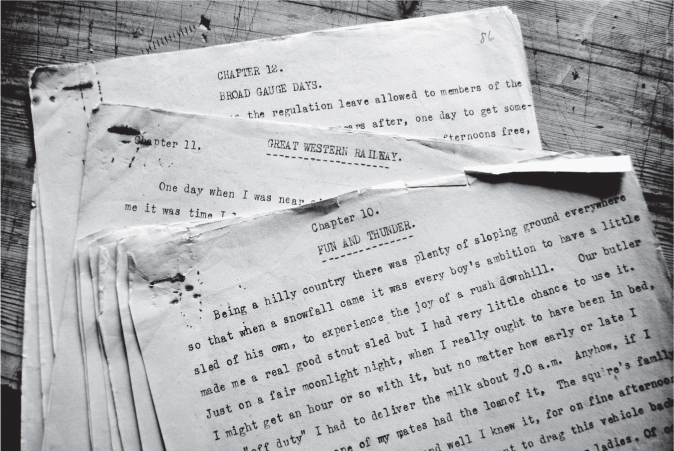

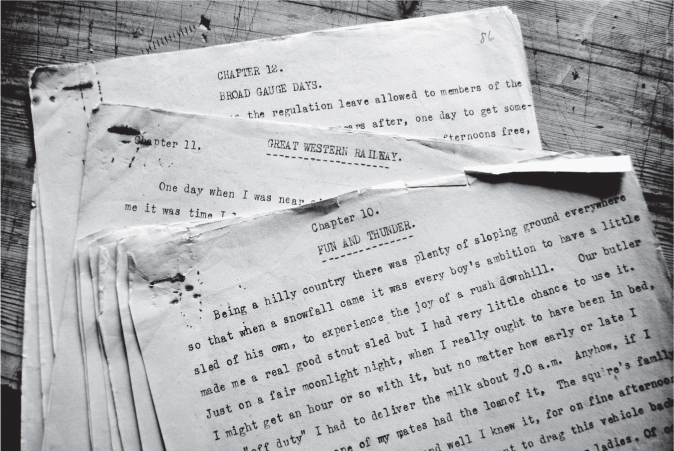

Pages from the original typescript. (David Wilkins)

SCHOOLBOY,

SERVANT,

GWR APPRENTICE

THE MEMOIRS OF

ALFRED PLUMLEY

18801892

EDITED BY

DAVID WILKINS

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

David Wilkins, 2017

To the original memoir Alfred Plumley, 2017

The right of David Wilkins and Alfred Plumley to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8333 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Cover illustrations

Front, clockwise from top: Mendip Lodge (Stan Croker Collection (original photograph c.1935 by George Love Dafnis)); The Cornishman Express passing the signal cabin at Worle Junction (Rev. A.H. Malan /Great Western Trust). Back, from top: A handwritten page from the original manuscript (David Wilkins); GWR locomotive Leopard (Great Western Trust).

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the following organisations and individuals for their help with my research: Jane Dixon and John Gowar of the Langford History Group; Raye Green and David Hart of Worle History Society; Elaine Arthurs at STEAM: Museum of the Great Western Railway, Swindon; Laurence Waters at the Great Western Trust Museum and Archive, Didcot; Sir David and Lady Wills, who allowed me to visit the gardens at Langford Court; Stan and Gill Croker; Charlie Wilkins.

I also thank the following people who read and commented on various sections of the draft book for me: Sue Forber; Mandy Hoang; Paul Morris; Anthony Orchard; Amy Rigg; John Sadden; Laurence Waters.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. To rectify any omissions, please contact the author care of the publisher so that we can incorporate such corrections in future reprints or editions.

INTRODUCTION

O n a cold, thoroughly miserable afternoon in January 2014, still in my scarf and woolly hat, zipped up in my warm coat, I was rooting around in the lots for sale at an auction saleroom in a Dorset seaside town. The wind off Lyme Bay rattled the windows. It felt colder indoors than outdoors.

In auction salerooms youll often hear people say, If only it could talk, in reference to some ancient, rustic chair or a pretty brooch that may have been a lovers gift. Occasionally, a little bit of research can reveal the past lives of such objects but, for the most part, furniture and jewellery, like china, bronze and glass, tend to be rather aloof. They regard their past as a private matter. It is in the dark spaces beneath the tables, where the battered cardboard boxes are, that there is gossip to be heard. Here are the lower social classes of the saleroom the mixed lots, the miscellaneous items and the ephemera. Here are bundles of letters tied up with string, old notebooks and diaries, and dog-eared documents that were once of the very greatest importance. These things are really nothing but a story.

After about half an hour, just when I was beginning to wish I had stayed home where it was warm, I picked up from such a box an old folder, clearly some decades old. It contained maybe 100 typewritten sheets held together in small batches by rusted staples. The paper was rather tatty and discoloured and the uneven lines suggested that the typewriters best days were already behind it when the typescript was made, but the top sheet of the bundle carried an intriguing title, though one which gave little away: Chip of the Mendips. As my cold, numbed fingers turned the pages, the document was revealed to be a memoir of some kind, written by an elderly man recalling his rural childhood and adolescence. It looked interesting. By the end of the sale the next day, it belonged to me.

That evening I sat down to read the memoir; the bare bones of it are easily summarised. It was written anonymously and described the life of a boy growing up in a village in the Mendip Hills in Somerset in the late nineteenth century. It began with the writers first day of school at the age of 5. Just after his twelfth birthday, his schooldays came to end and he immediately went into service as a pageboy at the big house nearby. At 16, with the help of the kindly lady of the house who wanted to encourage him into a trade, he took up a station staff apprenticeship with the Great Western Railway (GWR). Initially he worked as a lad porter at a village station and later he was transferred to the great city of Bristol to gain more experience.

When the writer turned 18 in 1892, his job with the GWR was confirmed as permanent. On that same day, to his great relief, he was transferred from Bristol back to a country station, at which point the memoir ended. However, the memoirist assured the reader that he went on to become a successful railwayman his entire working life was to be spent with the GWR.

The typescript itself was undated, but piecing together the clues it was possible to work out that the memoir was written sometime between 1954 and 1956, when the author was in his early 80s. He wrote it by hand in a notebook and it was typed up by a friend or relative; one leaf of the original handwritten version had survived and was loose inside the folder.

Of course, the immediate challenge was to identify the memoirist, but that presented a puzzle. The writer names himself just twice in the 40,000 words of text, on both occasions reporting other people speaking to him or about him. The first time he refers to himself only by the forename Alfred; the second time in reference to his surname only by the initial P. The places where he lived, went to school and worked are all given fictitious names (this little deceit, incidentally, dawning on me only after a frustrating hour poring over increasingly large-scale maps, first of the Mendip Hills and then of the whole of Somerset).

Because the place names were invented, there was of course the possibility that Alfred and/or the surname P were also fabrications. It could easily have been that the memoirist would prove impossible ever to identify, in which case this book could not have been written. On page eighty-four of the typescript, however, there was a crucial number: 15718. This number was the secret code in this spy story, the co-ordinates on the pirates treasure map, the combination to the safe holding the stolen documents. It was the writers GWR staff number, the number that appeared on his wage slip every week for forty-five years, the number that might give him a name.

The staff records of the GWR going back to the middle of the nineteenth century are stored at The National Archives in Kew and can be searched online. The records are not filed sequentially by staff number, so the only way to find our man was to look up with fingers crossed that Alfred was his real name every individual Alfred who started work with the GWR in the later 1880s or early 1890s (it was possible to roughly estimate this time period from other information in the memoir). After I had ploughed through the first four- or five-dozen ghosts of Victorian engine drivers, signalmen, porters, booking clerks, fitters and coachbuilders named Alfred, the number in the right-hand column of the staff records suddenly matched the number in the notebook on my desk. There, blinking in the spotlight after more than a century shut flat in the GWR staff ledger, was the author of the memoir: Alfred James Plumley.

Next page