Contents

- ONE

A Rendezvous - TWO

Unwanted - THREE

The Dying Rooms - FOUR

Population Control from Mao to Now - FIVE

The Road to China - SIX

The Orphanage - SEVEN

Saving Babies - EIGHT

Eating an Elephant - NINE

The Story of Orphan Fu Yang - TEN

Better Days - ELEVEN

Life and Loss - TWELVE

Shenanigans - THIRTEEN

Putting Out Fires - FOURTEEN

Jiaozuo Today - FIFTEEN

Uninvited Visitors - SIXTEEN

Outreach - SEVENTEEN

The Story of Ms Tian - EIGHTEEN

The God Factor - NINETEEN

Babies For Sale - TWENTY

The Family Tree - TWENTY-ONE

Forgotten - TWENTY-TWO

Forever Families

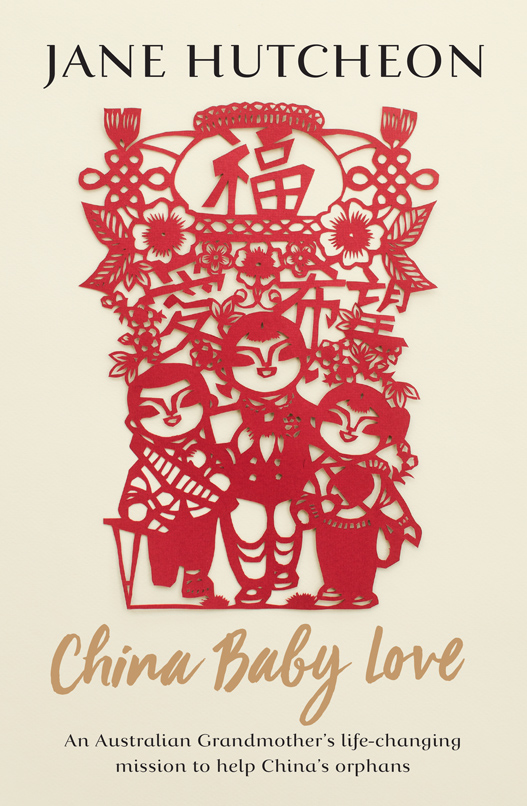

Guide

For Michael and Isla

O n a hazy summer day in 1930s Shanghai, a nine-year-old girl named Beatrice and her father Kit, arrived at The Bund to farewell visitors from Hong Kong. Aunt Rose and Uncle Alfred were heading home on a steamship, docked at the famous Shanghai waterfront. An outing to the pier was always exciting for a young girl. But suddenly, while she was still below deck admiring the cabin, she felt a shudder and realised the vessel was departing. It was too late to disembark. She didnt understand what was happening. Would her father, who was still waiting in the Studebaker on the pier, be worried or angry she wondered, as she raced out of the cabin to the deck and searched for him on the pier. She saw the black Studebaker first. Then she saw her fathers silhouette against the smooth cream-coloured passenger seat of the car. His face was buried in his hands. He refused to look up.

Unknown to Beatrice, her father and his sister, her Aunt Rose, had hatched a plan. Without the childs consent, Beatrice was being taken from her home in the leafy French Concession of Shanghai. She had not been given the option to say goodbye to anyone and now she was being uprooted from her school, her friends, her two brothers and sister, her cousins, and being sent to the British colony of Hong Kong to live with her Aunt Rose, Uncle Alfred and cousin Alec. Everything in the plan had proceeded smoothly so far and now here she was on the ship with Rose and Alfred, heading for her new home and a new, unfamiliar life in Hong Kong thirty-six hours away.

As a child in Shanghai, Beatrice was unwell much of the time. A few months before she was sent to Hong Kong, she contracted diphtheria and was rushed to hospital where surgeons performed an emergency tracheotomy. When she was four, her beloved mother, Elsie, caught meningitis and died. She has one faint memory of Elsie sitting at a sewing machine. The absence of a mother, combined with the idea that Hong Kong might be better for her health, led to the arrangement with Kits sister and brother-in-law.

Fortunately, though Aunt Rose was a disciplinarian and neither warm nor loving, Beatrice was doted on by her cousin and uncle and there were other relatives who showed her patience and kindness. She quickly found friends, a wonderful school and made a new and successful life for herself. This was very fortunate, because when Beatrice was fourteen, her father, Kit, still living in Shanghai with the rest of his family where he worked for a firm of chemists as a book-keeper, died suddenly. He had not seen his daughter since leaving her on the ship bound for Hong Kong. When Kit died, that made Beatrice, the youngest of four children, an orphan.

Beatrice is my mother. More than eight decades after she left Shanghai on the slow-boat to Hong Kong, she is still alive and well into her nineties. She often says that, although the early part of her life had its challenges, the latter part more than made up for the hardship. Im thankful that she had relatives to care for her. Even though their care wasnt perfect, she wasnt given up to an orphanage. Losing her mother at such a young age would have been a terrible trauma, although in those days, any child who suffered a tragedy was expected to just get on with life. Setbacks unfolded, particularly around the time of the Second World War. But you didnt complain or feel like a victim. You were told to put one foot in front of the other. Thats the way it was.

As a result of my mothers experience, child abandonment is something that has always tugged at my emotional core. From an early age, I was drawn to stories of orphans from Cinderella, and Peter Pan, to the world of Oliver Twist. I graduated to the comic strip Little Orphan Annie and later on when I had a daughter of my own, she introduced me to additional orphan characters like Sophie from the BFG and of course the boy wizard, Harry Potter.

My mother left Shanghai long ago and happened to meet my father, who, like her, was born in Shanghai so it would be fair to say that Shanghai, or China, has never really left me. China hasnt always been a love affair, but its most certainly an ongoing fascination. So when I came across the work of an Australian woman named Linda Shum who decided to dedicate her life to an orphanage in what she likes to call the real China (because its not one of the big, flashy cities we usually hear about in the news), it was hard for me to walk past.

There are hundreds of foreign non-governmental organisations (NGOs), like Linda Shums, working to improve the lives of Chinas orphans. Even NGOs that have legally registered partnerships with local orphanages (like Lindas organisation COAT has) feel they operate in a shadowy world where they can never be sure of what the future holds, where one wrong step or criticism can result in the loss of everything they have built up so far. Others face significant funding pressures as China becomes an increasingly expensive place to live in and to do business in. And of course, the biggest fear is that the childrens lives that they have worked to improve, will somehow slip backwards.

On the other hand, there are international experts, including Professors Xiaoyuan Shang and Karen Fisher at the University of New South Wales, whose research is contributing to Chinese government policy and creating reform within Chinas child welfare system.

China is a country which produces an incredible array of statistics. It has a population of 1.38 billion, more than 300 million children, and more than one million orphaned or abandoned children. About 110,000 of these orphans are state wards, the majority of them (80 per cent) living in institutions and orphanages. An estimated 60 million children live separately from their parents who have left home to find work elsewhere in China. Parents leave their children behind because of strict residency controls which can affect education and healthcare.

China maintains that the one-child policy that was in place for thirty-five years from 1980 only applied to 36 per cent of its population and that 53 per cent were allowed to have a second child if the first was a girl. In the coming pages, you will hear about the negative side-effects of the one-child policy.

Linda Shum opened her world to me, introducing me to her network in China and beyond. The stories in this book belong to Linda and her ever-widening net. Linda is happy to ponder the deeper questions such as why a Chinese couple today is willing to abandon an infant with a physical disability such as a missing left hand. But she is more concerned about how to give abandoned children the best start in life, to give them an education and, if necessary, to guide them to adulthood. I admire her work. However, I am often speechless concerning why child abandonment remains widespread and why so little is done by the Chinese government to reduce abandonment and address disability discrimination.

Next page