Copyright 2016 by Janelle Dietrick

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the author is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, should send inquiries to janelledietrick@comcast.net.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dietrick, Janelle.

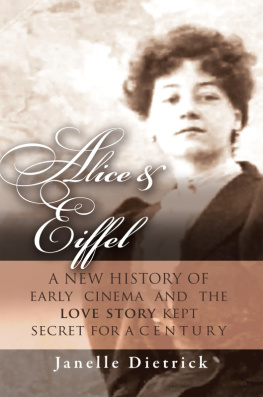

Alice & Eiffel, A new history of early cinema and the love story kept secret for a century / Janelle Dietrick.

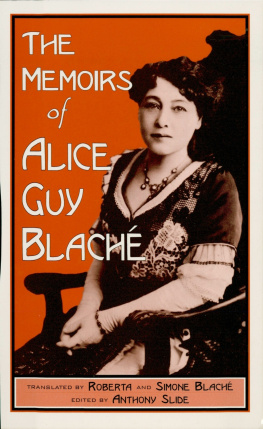

Excerpts from The Memoirs of Alice Guy Blach translated by Roberta and Simone Blach, edited by Anthony Slide, copyright 1996, used by permission of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Includes biographical references.

ISBN 978-1-68222-767-1

1. Blach, Alice Guy 1873-1968CinemaFranceUnited StatesBiography.

2. Eiffel, Gustave 1832-1923CinemaFranceUnited StatesBiography.

BookBaby

13909 N.E. Airport Way

Portland, OR 97230

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PROLOGUE

La vie explique loeuvre. The life explains the work.

Anonymous

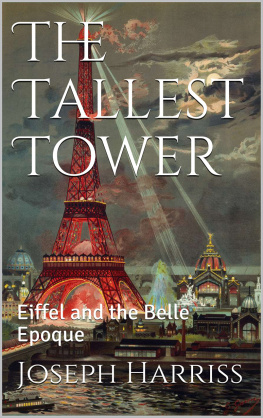

On top of the Eiffel Tower, a thousand feet above Paris, is an apartment the worlds most famous engineer built for himself. He had a house in nearby Sevres and a mansion on rue Rabelais, but Gustave Eiffel turned them both over to his daughters who were raising young families. He lived at his rue Prony apartment near his workshops in Levallois-Perret, but when he entertained the leading scientists, musicians and artists of his time, he served champagne and petit fours at the top of the tower far into the night.

Twelve years before the tower was completed, his wife had died, leaving him with five children, ages four to fourteen. Still, there is no record of his having a relationship with a woman for the remaining forty-seven years of his life. In 2009, an exhibit of the Muse dOrsays collection of Eiffel memorabilia was held in the Hotel de Ville. A journalist reviewing the exhibit commented on the lack of knowledge about Eiffel:

Besides portraits, photographs, a bust, we do not know much about what he was thinking or feeling, no secrets. In all his portraits, young or old, this is the same face that always appears, expressionless, decorous, but satisfied without vanityhe fences, he swims, he dances, leaving no trace of sin, even venal, according to the current knowledge of the museums archives.

Late in his life, Eiffel wrote his Biographie Industrielle et Scientifique documenting his engineering achievements and his pursuit of aeronautic science. He made five copies of it, one for each of his children. He left out any mention of his work at L. Gaumont et Cie, one of the worlds oldest motion picture studios, where he was president for its first eleven years. The accepted view for more than a century has been that Eiffel was merely a silent partner in the Gaumont company, contributing start-up capital and little else. This book will show that, although Eiffel kept a low profile, he guided the company, contributed to its inventions, and was absorbed by the new technologies and decisions the company made in its first eleven years.

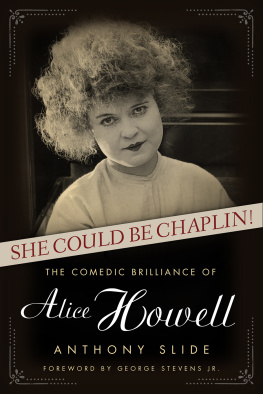

It comes as a surprise to most people that the cinema started in Paris in 1895, fifteen years before the first studio was built in Hollywood, and that the first film director was a young woman named Alice Guy who worked at Gaumont. The first films were only a minute long, long enough for a vignette from real life, a novelty with little utility. Alice at age twenty-two used the motion picture camera to stage a scene, a story showing babies growing in a garden of enormous cabbages. It was the first of hundreds of short films Alice wrote and directed. For eleven years, Alice made films in Paris and then in 1907 she came to the United States, where she wrote and directed hundreds of longer films in New York and Fort Lee, New Jersey, before Hollywood became the center of the film industry.

Alices memoirs were published posthumously in France in 1976 and translated into English ten years later. Her relationship with Eiffel is alluded to but well camouflaged. By the time Alices memoirs were published, many biographies of Eiffel had firmly established the accepted facts of his life. For almost a century, biographers have noted that he never remarried after his wife died in 1877 and that he was very close to his oldest daughter.

Eiffels biographers all respectfully took as their starting point Eiffels brief autobiography that describes in detail his education and career up until just after he built the Eiffel Tower. After that, there is a decade-long gap. There is an emptiness to this period of Eiffels life that is inconsistent with everything we know about this man. He loved opera and photography and had many friends. He simultaneously conceived the Eiffel Tower and the Panama Canal, two of the worlds greatest feats of engineering, and then, according to the current state of the knowledge, he had nothing to do for the next ten years.

There is a corresponding gap in Alices memoirs. After falling in love in 1891 at eighteen with a mysterious older man she calls P.B., she makes no reference to any romantic liaison until her marriage at age thirty-three in 1907. There have been two biographies of Alice, one in English and one in French. Both focus on Alices career as a film pioneer and director. More recent research is dedicated to locating the lost treasures of Alices films, unidentified and unrestored in archives all over the world.

The brevity of Alices memoirs, little more than a hundred pages, has flummoxed researchers for decades. It has been called tangential and incomplete, This book is about what Alices memoirs leave outthe people introduced but not described, the difficulties alluded to but minimized, the losses and triumphs barely mentioned, and the love story she felt compelled to keep secret.

Ironically, without Alices words, this study would not be possible. Although she never identified the man she fell in love with by name, if she had not written, I was literally in love with him, or if she had not said in an interview, I would gladly have married himI adored the man, no amount of research could discover the nature of her feelings.

Alice fell in love with Eiffel when she was eighteen and he was fifty-eight, and they both had good reasons for keeping it a secret for the rest of their lives. Alice and Eiffel continued their relationship for more than fifteen years. He was the love of her life. He was brilliant and meticulous, handsome and physically fit, generous and kind-hearted.

While Eiffel is fascinating, Alice is endlessly intriguing. What began as a double biography about a man and a woman, both of them extraordinary, turned out to be more about her. She is reserved, but her feelings are plainly declared on her face. She looks happy in some pictures, in others, sad, resigned or wistful. The problem for researchers has been that there is a dearth of personal information on either Alice or Eiffel, but when you put them together, there is more information on both of them. Alices memoirs are like a treasure map cluttered with seemingly meaningless details that on examination become clues to her core of experience.