Critical acclaim for the first edition of The Tallest Tower

An interesting story interestingly told, and as such it is welcome offers a particularly clear description of Eiffels engineering principles, skillfully woven into the narrative. The New York Times

Fascinating and highly instructive ... a book not to miss. Janet Flanner, Paris correspondent, The New Yorker

A comprehensive account of the man who designed and built [the tower], the period out of which it came and the significance it has assumed in art, engineering and architecture. The book is written with wit and charm. Los Angeles Times

This volume is a delightful illustrated social history of the tower telling the full story of the structure, so intricately twined with contemporary history. Scientific American

Mr. Harriss has told the towers story with conscientious zest, packing his account with anecdotes and historic details. The Christian Science Monitor

Certainly the best biography of a building and the cultural climate which spawned it weve read in a very long time. Kirkus Reviews

Harriss succeeds admirably This is a well-organized, exceptionally readable book; entertaining, informative, and highly recommended. Library Journal

Marvelously evocative portrait of Gustave Eiffel and the technological daring, engineering know-how, and romantic vision which have made his tower a landmark. American Library Association Booklist

Pleasant, thorough book the Eiffel Tower emerges as a vibrant flagstaff to freedom, a scientific testing ground, a gigantic frivolity and a surprising aesthetic triumph. Publishers Weekly

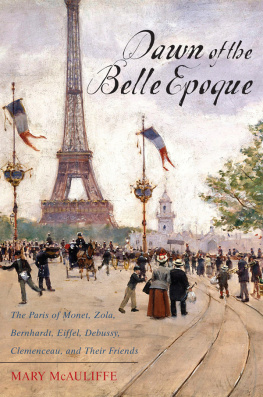

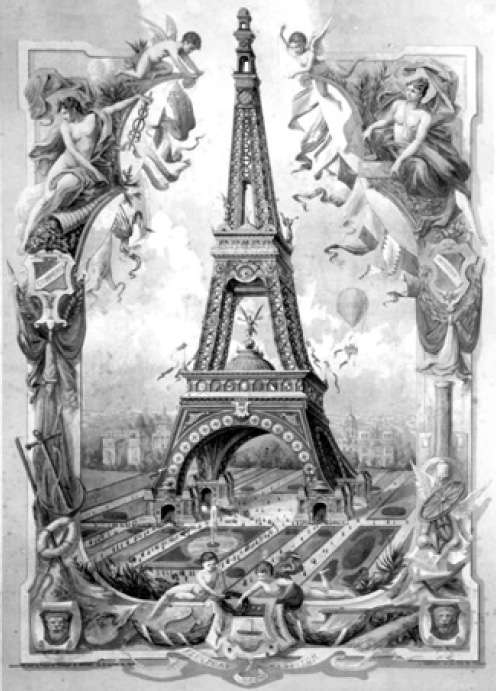

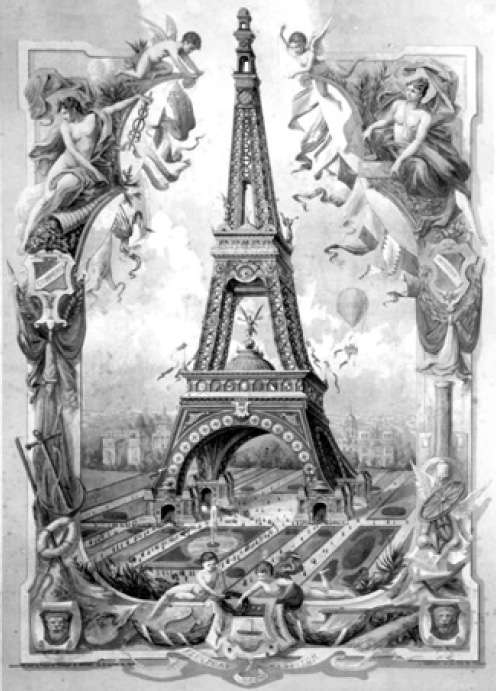

An early promotional illustration of the Eiffel Tower before its construction.

(Collection Tour Eiffel)

The Tallest Tower

Eiffel and the Belle Epoque

New Edition, Revised and Updated

Joseph Harriss

Copyright 2004 by Joseph Harriss

All rights reserved under Title 17, U.S. Code, International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording, broadcast or live performance, or duplication by any information storage or retrieval system without prior written permission from the author(s) and publisher(s), except for the inclusion of brief quotations with attribution in a review or report.

Cover image background: Painting by Georges Garen, Embrasement de la Tour Eiffel pendant lExposition universelle de 1889, done January 1889. Public domain.

Credits for artwork, where appropriate, are given with each illustration.

Library of Congress Control Number 2004107253

Second edition.

This version includes additional chapters updating the book through 2004.

First hardback edition published by Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston: 1975.

First paperback edition published by Regnery Gateway, Washington: 1989.

Second paperback edition published by Unlimited Publishing, 2004.

ISBN 978-2-900785-02-7

Digital book(s) (epub and mobi) produced by Booknook.biz.

To the memory of my father, an engineer.

Prologue

ONE EVENING I took a random stroll on the Champ de Mars, not far from my home in Paris. After walking for a while, I found myself beneath the Eiffel Tower and glanced up. Above me the colossal, intricate, overarching tracery of crisscrossing girders soared more majestically than the columns of any gothic cathedral. Although I had looked at the tower countless times during my years as a Paris-based journalist, this time I saw it. I was held, fascinatedawe-struck is not too strong a word. I decided to find out more about this odd, captivating structure. I learned that the tower was not merely a fairground gimmick, but the all-but-inevitable outgrowth of an era, in some ways the epitome of an age.

In France, that age coincided with the countrys third, precarious attempt at democracy in the space of less than a century, after its long history of monarchy and empire. The Third Republic was conceived in the confused aftermath of Frances humiliating defeat by the Prussians in 1870. The era ended 69 years and 107 French governments later, in the debacle of Frances abject capitulation to Nazi Germany in 1940. Between those worst of times, however, many French citizens lived in what may have been one of the best of times.

The Belle Epoque, like the Renaissance and other neat labels bestowed by historians, was not a pat, monolithic era. It was a tumultuous time of tension and contradiction, change and anticipationand, yes, even terrorismmuch like our own. But it does appear that there was a period toward the end of the 19th century when new prosperity and old values fused briefly to produce an era in many ways happier, or at least less riddled with doubt and anxiety, than any we have known since.

This was the age that, with a remarkable sense of itself, created the Eiffel Tower. A synthesis of technology and mood, this bizarre construction was a compendium of engineering methods and materials developed during the first century of the Industrial Revolution. It was also, it seems to me, the most expressive statement of how one part of the human race felt about itself at a pivotal point in its history.

One

A Fair for France

THE FRENCH WERE not alone in enjoying the momentary state of grace known as the Belle Epoque. Most of northwestern Europe and the northeastern United States experienced it in recognizably similar formthe Gay Nineties. But if Frances euphoria in the last years of the 19th century appears heightened, the impression is perhaps due to a backdrop of travail. For the Franco-Prussian War, in which the Imperial Army of Napoleon III was smashed in a matter of weeks, was not merely a military defeat.

The war led to the loss of Frances large eastern provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, with a population of nearly a million and a half, economically vital mines and industries, and the great city of Strasbourg. Moreover, the settlement that President Adolphe Thiers made with the Germans in February 1871 involved an enormous and debilitating indemnity of five billion francs, or about one billion dollars. It also stipulated that German troops would occupy the countrys eastern region until the sum had been paid.

Parisians in particular had borne much of the brunt of the war, undergoing a five-month siege during which they were reduced to eating cats, rats, and the animals in their zoos. No sooner had peace been concluded than the revolt of the Paris Commune broke out on March 18. A political insurrection in the image of those that had shaken Paris sporadically for a century, the Commune revolt was sparked when President Thiers suspended payment to national guardsmenthe only income of many families because of severe unemployment at the timeand ended a moratorium on rents and bills.

Moreover, Parisians felt increasingly isolated and misunderstood when the National Assembly moved to Versailles to escape the seething resentment in the capital. The national guardsmen of

Montmartre and Belleville, on the north side of Paris, refused to yield their weapons, including over 200 cannons, when ordered to disarm. They proclaimed the independent, self-governing Commune of Paris, and for two months the city was ravaged by fire and divided by barricades as 30,000 Communards held out against 130,000 government troops. When Marshal MacMahons army finally quelled the revolt after bloody street fighting, nearly 20,000 Parisians had died at the hands of their compatriots. Entire areas of the city lay in ruin.

Next page