Table of Contents

ALSO BY JILL JONNES

Conquering Gotham

Empires of Light

Hepcats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams

South Bronx Rising

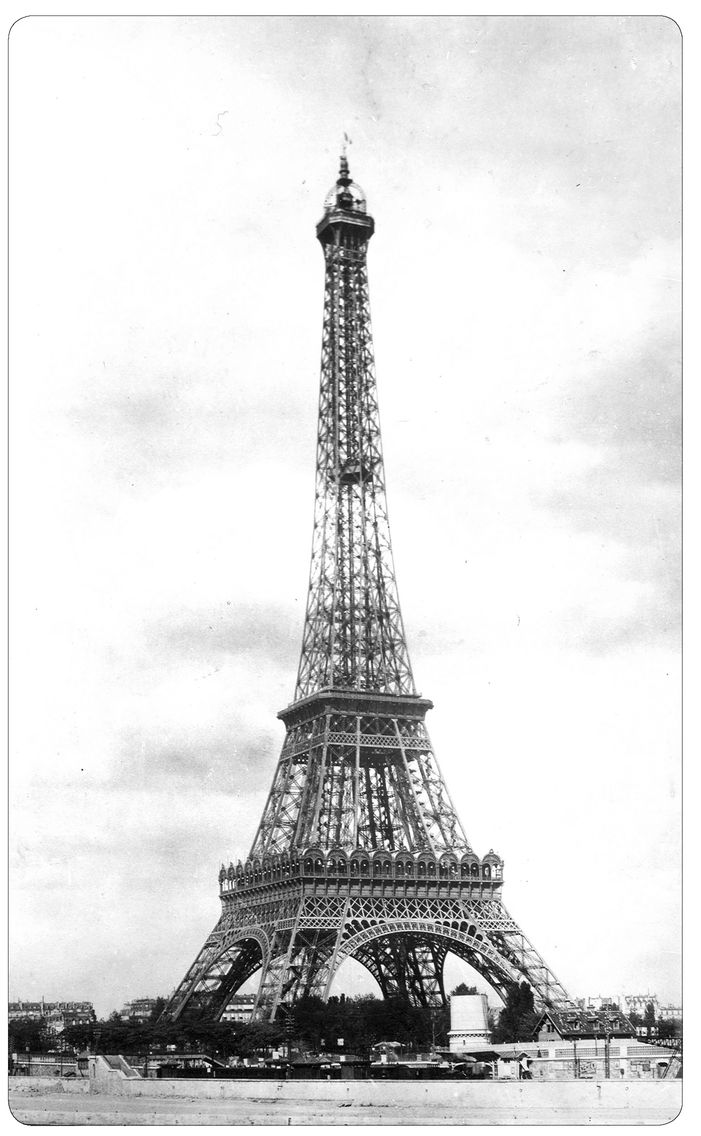

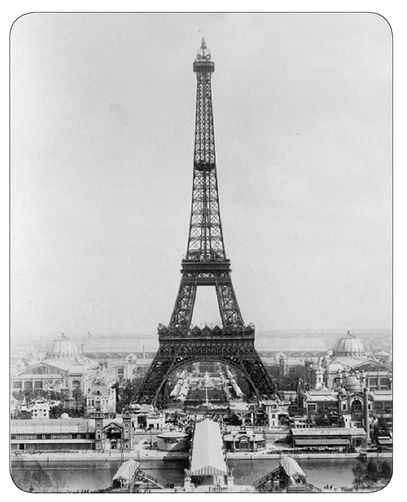

Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1889

To my mother and father, Lyn and Lloyd Jonnes, and the years our family enjoyed being Americans in Paris

The Eiffel Tower and the 1889 Paris Worlds Fair

CHAPTER ONE

We Meet Our Characters, Who Intend to Dazzle the World at the Paris Exposition

On the cold afternoon of January 12, 1888, Annie Oakley was sitting comfortably in her apartment across from Madison Square Garden in New York, making tea and toasting muffins, when she heard a knock at the door. Her visitor was a journalist from Joseph Pulitzers New York World, come to hear what Americas most celebrated sharpshooting female was up to. He stepped into the cozy space to find a great jumble. The sitting-room, he reported, was littered with breech-loading shotguns, rifles, and revolvers, while the mantel-piece and tables were resplendent with gold and silver trophies brought back from Europe by this slender yet muscular Diana of the Northwest. Fted and lionized by an enthralled Old World aristocracy, Oakley, twenty-seven, had returned home triumphantly three weeks earlier bearing lavish tokens of admiration, now displayed all round the apartment: two sets of silverware, a solid-silver teapot, antique sugar bowls. As for the pure-bred St. Bernard, it was en route with her horses. I suppose a crack shot in petticoats was a novelty and curiosity to them, she said between sips of tea.

Nor was that all, she confided to the reporter: her fame as the star attraction of Buffalo Bills Wild West show in London had inspired four offers of marriage, including one from a French count. A Welshman had sent along his photo with his proposal. I shot a bullet through the head of the photograph, said Annie, and mailed it back with respectfully declined on it.... I am Mrs. Butler in private life, although always Annie Oakley on the bills. She regaled the reporter with stories of meeting the king of Denmark and the Prince and Princess of Wales, laughing merrily as she told of a close scrape in Berlin, where she had found the avenue to her hotel closed during the Russian czars visit. Determined to reach her room, she had dashed through a police barrier and been hotly pursued: I rolled under an iron gate and spoiled my clothes, and the enraged guards went plumb against the gate.... Of course, I laughed at their discomfiture, but I tell you I was a bit scared when I remembered that I had a box of cartridges with me. Why, if they had caught me I should have surely been held as a Nihilist.

A petite, attractive woman who had started shooting game at a young age in Ohio to help her widowed mother feed the family, Annie was also a virtuoso seamstress who designed, sewed, and embroidered her own beaded and fringed cowgirl costumes. Performing with the Wild West, she had been catapulted to stardom as Americas best-known woman sharpshooter. In 1884, when Chief Sitting Bull joined the Wild West for a season, he adopted her, naming her Little Sure Shot.

She looked innocent and above reproach, observed biographer Shirl Kasper, a sweet little girlyet was a sharpshooter of matchless ability. That paradox was part of her appeal. She had a pleasant, wide smile, and thick, dark hair cut close around her face and worn long in back, falling over her shoulders. There was magnetism in the way she smiled, curtsied in the foot-lights, and did that funny little kick as she ran into the wings. Of future plans after her success across the pond, Annie Oakley revealed to the Worlds reporter only this: I will practice horseback shooting, and that Europe might beckon once again in 1889, as I have very flattering offers from there.

Soon enough Annie Oakley and a lively crowd of Gallic and American go-getters, artists, thinkers, politicians, and rogues would be making Belle poque Paris their stage, for the French republican government was organizing the most ambitious Worlds Fair yet, the Exposition Universelle of 1889. While the year marked the centennial of the fall of the Bastille, the government preferred to highlight more noble sentiments: We will show our sons what their fathers have accomplished in the space of a century through progress in knowledge, love of work and respect for liberty, proclaimed Georges Berger, the fairs general manager. Since 1855, the French had been holding an international exposition in Paris every eleven years (more or less), each more gigantic and wondrous than the last. This particular exposition was to be an advertisement for the Republican system, which for 18 years had kept at bay the Royalists and Bonapartists on the right and the representatives of various socialist tendencies on the left. The philosophy in power was to be seen as humanist, philanthropic, opening its arms to all of humanity. Already, the French and the Americansrepublican allies but also rivalswere looking to make their respective marks at this Worlds Fair, each determined to uphold national honor at what might be the last great international exhibition of the nineteenth century.

As 1888 began, Parisians looking at their familiar skyline, dominated by the gilded dome of Les Invalides and the towers of Notre Dame, also saw poking up over on the Champ de Mars, the tried-and-true site of the 1867 and 1878 expositions, Gustave Eiffels under-construction Tour en Fer de Trois Cents Mtres. Alternately mocked, despised, and admired, Eiffels tower was the chosen centerpiece of the upcoming Exposition Universelle. This astonishing structure had become the most conspicuous and controversial symbol of industrys ascendancy, and the triumph of the modern. Eiffels tower was to be the worlds tallest structure, the thrusting symbol of republican France, visible from every direction, the perfect monument to preside over the rococo Worlds Fair rapidly rising around its four latticed legs.

Gustave Eiffel had been relentlessly pushing to ensure his tower would be finished by May 1889. A self-made millionaire, Frances most successful railway bridge builder, and an engineer of global ambition, Eiffel had company offices in such colonial outposts as Peru, Saigon, and Shanghai. Attired in black frock coat, vest, and striped trousers, Monsieur Eiffel wore a high starched white collar, a cravat, and a silk top hat. His dark beard was kept neatly trimmed to a point; his hooded blue eyes missed nothing. Stolid and imperturbable, he could be found most dayssun, rain, snow, sleetat the Champ de Mars, perched on the construction platform directing his men as they assembled the colossal wrought-iron tower. For nine months Parisians had watched in fascination as the slanting legs of the much-discussed structure rose visibly week by week. The many who loved to hate even the idea of Eiffels tower felt quite vindicated, for the partially built tower now looked like an ugly, hulking creature.