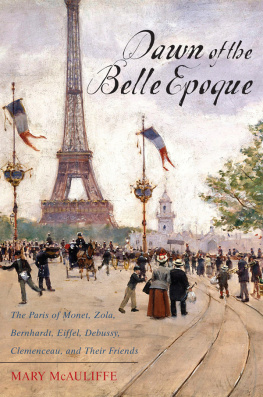

Dawn of the Belle Epoque

Dawn of the Belle Epoque

The Paris of Monet, Zola, Bernhardt, Eiffel, Debussy, Clemenceau, and Their Friends

Mary McAuliffe

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, inc.

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Distributed by National Book Network

Copyright 2011 by Mary S. McAuliffe

When not otherwise noted, all translations are by the author.

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McAuliffe, Mary Sperling, 1943

Dawn of the Belle poque : the Paris of Monet, Zola, Bernhardt, Eiffel, Debussy,

Clemenceau, and their friends / Mary McAuliffe.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-0927-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-0929-9

(electronic)

1. Paris (France)History19th century. 2. Paris (France)History20th

century. 3. Paris (France)Intellectual life19th century. 4. Paris (France)

Intellectual life20th century. 5. Arts, FrenchFranceParis19th century.

6. Arts, FrenchFranceParis20th century. 7. French literature19th century.

8. French literature20th century. I. Title.

DC735.M43 2011

944'.361081dc22

2011003611

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements ofAmerican National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paperfor Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements ofAmerican National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paperfor Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For Jack

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book is about Paris, and so it is fitting that I pay tribute here to the City of Lightto the streets and quarters where the people I have written about worked and lived, and to the many museums that provided me with invaluable resources and inspiration. These include the Muse Carnavalet (Muse de lHistoire de Paris), the Muse dOrsay, the Muse Marmottan-Monet, the Muse Rodin, the Petit PalaisMuse des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, the Maison de Victor Hugo, the Muse Clemenceau, the Muse de lOrangerie des Tuileries, the Muse de Montmartre, the Muse Cognacq-Jay, the Muse Bourdelle, the Muse des Arts et Mtiers, the Muse des Arts Dcoratifs, the Muse Fournaise (Chatou), and the Muse de la Grenouillre (Croissy-sur-Seine).

In New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has been an important resource, and I am especially indebted to the outstanding research division of the New York Public Library, including its Art and Architecture collection and its Library for the Performing Arts, where I have spent countless hours. I am also indebted to the many specialized studies and published letters, diaries, and memoirs to which I have given specific credit in my notes and bibliography.

Along the way, numerous friends and associates have provided valuable help and assistance. I am especially grateful to Susan McEachern, editorial director at Rowman & Littlefield, for her vision, guidance, and support. My thanks as well to assistant editor Carrie Broadwell-Tkach and senior production editor Jehanne Schweitzer for their professionalism and skill in making this book a reality. I am also greatly indebted to Mark Eversman, my longtime editor at Paris Notes .

From start to finish this book has been a labor of love, an adventure that I have undertaken and completed with the steadfast and enthusiastic assistance of my husband, Jack McAuliffe. It has been a team effort, and it is in this spirit that, with thanks and love, I dedicate it to him.

Introduction: The Terrible Year

(18701871)

The phrase Paris Commune may mean little or nothing to most Americans, but it still resonates with meaning for many French, especially Parisians, for whom it conjures up either fearful images of bloodshed and destruction or memories of a noble cause brutally suppressed. The viewpoint of course varies, depending upon ones politics and, still to some extent, ones class. But nonetheless, it resonates. Unlike Americans, the French remember their historyperhaps because they live so closely with tangible vestiges of their past. And if Belleville and Montmartre no longer summon up the images of danger and despair that they once did, then the simmering banlieues just beyond certainly do.

So return a century and a quarter to the year 1871. Louis Napoleon, Bonapartes nephew and ruler over the Second Empire, had been captured the previous autumn by the Prussians, after unwisely starting a war with them and their magnificent army. Parisians promptly overthrew his imperial government and established a republic, which attempted to carry on the fight. But by this time, Paris was surrounded by the Prussian army, which was intent on starving the city into submission. After four months of deprivation, during which almost all the horses of Paris (as well as, most famously, the rats) turned up on dinner plates, the French government capitulated. A new government, far more conservative than the old, agreed to peace terms that the belligerently patriotic working class of Paris found humiliating and unacceptable. In March 1871, the workers of Paris rose up in revolt.

The opening shots of this bloodbath took place on the Butte of Montmartre, in a now-obscure spot presently commemorated only by a historic marker. The current address of this sitelocated just behind Sacr-Coeuris 36 Rue du Chevalier-de-la-Barre, but in 1871 it was 6 Rue des Rosiers. Here, all hell broke loose after the government sent troops to recover some two hundred cannons that the citizens of Montmartre had dragged all the way from the Place de Wagram to the top of the Butte. Having subsidized these cannons through public subscription, the men, women, and children who participated in this dramatic transfer believed them to be theirs and were determined to keep them safely out of Prussian hands. The government strongly disagreed on the question of the cannons ownership and certainly did not want to see such weapons in the hands of Pariss volatile poor. A confrontation ensued, during which two generals were captured and dragged to 6 Rue des Rosiers, where they were shot.

The spot looks quite different now, as you can readily see from contemporary paintings of Montmartres Tour Solfrino, a popular guinguette , or tavern and dance hall, then located on the present site of Sacr-Coeur. The dazzling white Sacr-Coeur, which went up in the Communes aftermath, was erected in expiation for the sins of France, but its conservative Catholic promoters had little sympathy with the Communards. Not coincidentally, the basilica completely hides the ground where the cannons were parked and the uprising first broke out.

Following Montmartres opening shots, Pariss workers quickly established their own government, the highly contentious but socially conscious Commune, which took over the Htel de Ville. Members of the official French government, under Adolphe Thiers, raced for the safety of Versailles, well beyond Pariss massive walls. Ironically, these walls (and the sixteen muscular forts just outside them) had been built during the 1840s at the instigation of none other than Thiers himself, who well knew their strengths and weaknesses. Their only soft spot was in their southwestern sector, at Auteuils Point-du-Jour. Thiers proceeded deliberately, but finally, on the night of May 21after a lengthy cannon bombardment of western Paris and the capture of Fort dIssy and other nearby fortressesgovernment troops poured into Paris.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements ofAmerican National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paperfor Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements ofAmerican National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paperfor Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.