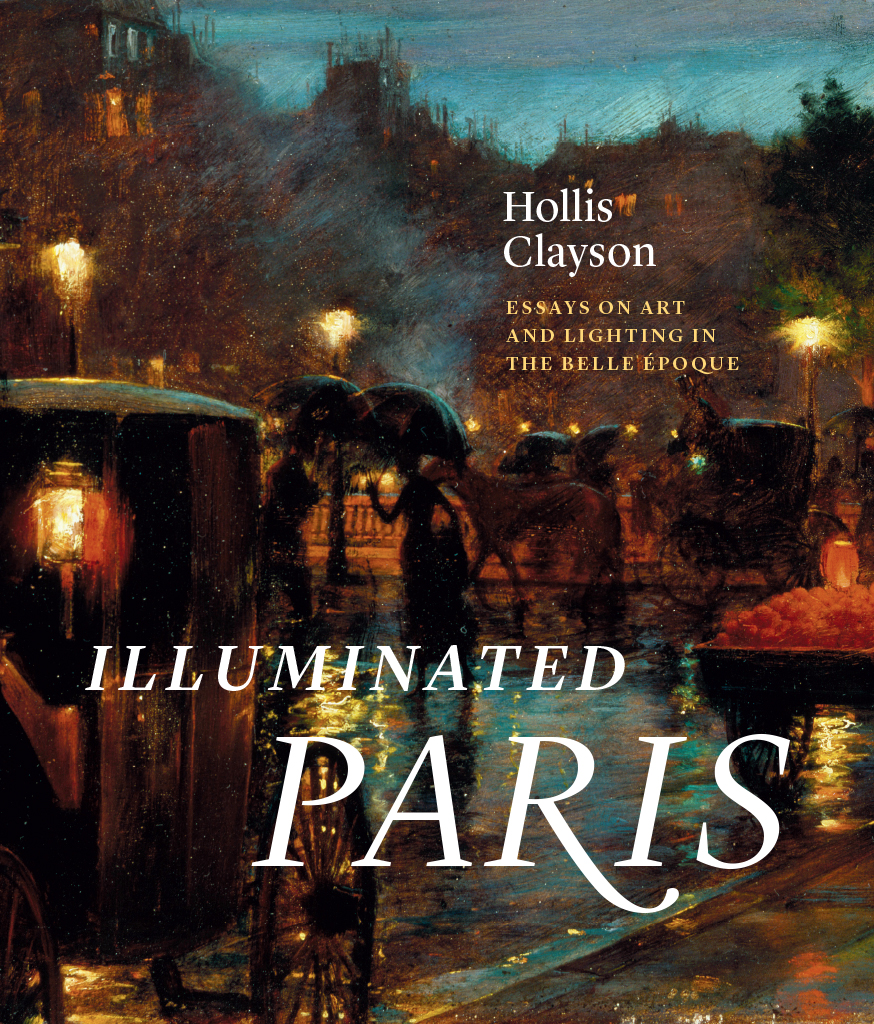

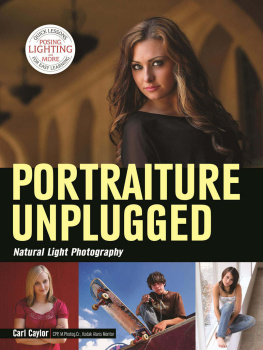

Illuminated Paris

Illuminatedd Paris

Essays on Art and Lighting in the Belle poque

Hollis Clayson

Publication is made possible in part by a gift from Liz Warnock to the Department of Art History at Northwestern University

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago & London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in China

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-59386-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-59405-7 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226594057.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clayson, Hollis, 1946 author.

Title: Illuminated Paris : essays on art and lighting in the belle poque / Hollis Clayson.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018029034 | ISBN 9780226593869 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226594057 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Paris (France)in art. | Lighting, Architectural and decorative, in art. | Art, Modern19th century.

Classification: LCC N8214.5.F8 C539 2019 | DDC 709.04dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018029034

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Maxwell Dean Cogbill (born 2017)

Contents

Charles Marville, Gustave Caillebotte, and the Gas Lamppost

John Singer Sargent in the Jardin du Luxembourg

Electric Light Caricatured

Illumination in the Prints of Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas

Americans in Paris

Edvard Munch in Saint-Cloud

Books that take a long time incur many debts, but a recent witty review made me rethink extended acknowledgments. The reviewer dispatched a baggy set of thank-yous with a waggish putdown: if only half of those mentioned bought the book, he observed, it would be a best seller. I was chastened by this witticism, and, as a result, I will be brief. Please know, however, that the institutions and individuals I name have my deepest gratitude.

The Clark Art Institute and the Getty Research Institute awarded fellowships to the project when it centered exclusively on Americans in Paris, emphasizing Mary Cassatt. As I began to focus on artificial illumination, fellowships from the Clark Art Institute (again), Reid Hall, Columbia University (Paris), and the Huntington Library were indispensable. During the course of work on the book, three invited professorships put me in dialogue with generous and brilliant interlocutors: the Sterling Clark Visiting Professorship, Williams Graduate Program in Art History; the Samuel H. Kress Professorship, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art; and the Kirk Varnedoe Visiting Professorship, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Two exhibitions, both entitled Electric Paris, refined my approach to art and illumination in critical ways. At the Clark Art Institute (2013), the show I co-curated with Sarah Lees was brought into being by Jay Clarke with support from Elizabeth Liebman, and at the Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut (2016), Susan Ball and Margarita Karasoulas spearheaded the exhibition, for which I served as advisor. During intensive research campaigns, the librarians and archivists of the Bibliothque Nationale de France (Paris), the Bibliothque du Muse des Arts Dcoratifs (Paris), the Huntington Library (San Marino, California), the Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles), the Clark Art Institute Library (Williamstown, Massachusetts), and the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries (Evanston, Illinois) were flawlessly helpful.

Illuminated Paris benefited from the research assistance, transformative suggestions, and kind invitations of a far-flung constellation of individuals. In alphabetical order, I thank Caroline Arscott, Patricia Berman, Sarah Betzer, Alexander Bigman, John Brewer, Bill Brown, Franois Brunet, Matti Bunzl, Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen, Catherine Clark, Jean-Louis Cohen, Elizabeth Cropper, Thomas Crow, Justine De Young, Andr Dombrowski, Arne Eggum, Hannah Feldman, Lily Foster, Caroline Fowler, Ernie Freeberg, David Getsy, Marc Gotlieb, Linda Green, Joseph Hammond, Jodi Hauptman, Mark Haxthausen, Lee Hendrix, Steve Hindle, Michael Ann Holly, Katie Hornstein, Sandy Isenstadt, Heather Belnap Jensen, Jonathan D. Katz, Ara Kebapiolu, Sarah Kennel, Scott Krafft, Jason La Fountain, Keith Leitsche, Michael Leja, Rob Linrothe, Peter Lukehart, Rgis Michel, Kent Minturn, Mary Morton, John Murphy, Kevin D. Murphy, Dietrich Neumann, Andrew Nogal, Therese OMalley, Peter Parshall, Todd Porterfield, Dominique Poulot, Hector Reyes, Franoise Reynaud, Jennifer Roberts, Mary Roberts, Patricia Rubin, Tina Rivers Ryan, Vanessa Schwartz, Mark Simpson, Nancy Spector, Harriet Stratis, Veerle Thielemans, Krista Thompson, Hlne Valance, David Van Zanten, Susan Wager, and Andrs Zervign. At the University of Chicago Press, I worked with the best: nonpareil editor Susan Bielstein, her right hand James Whitman Toftness, and two anonymous readers who made all the difference.

Paris, City of clairage

Granted that the art of lighting [clairage] cannot be the monopoly of any country or capital, it is certain that it owes its development principally to Paris.

Henri Marchal, 1894

For some artists enthralled by light, aesthetic curiosity about night and its artificial illuminations coexisted with the better-known love affair with the nuances of daylight. This book homes in on a sequence of Paris-based art practices that were guided by modern illumination. The resultant art works interrogated the visibility/invisibility dialectic, a central preoccupation of the era, from a wide range of approaches in a variety of aesthetic forms.

The argument that cuts across all the chapters is not that new lighting simply provided new motifs (new subject matter) for the fact-based visual arts, but rather that the lights plus the heated discussions they provokedwhat I call illumination discoursehelped to shape many modernity-oriented art practices centered on Paris. We will discover that this convergence of technology and discourse defined a philosophical and visual matrix of paramount importance to the New Painting, a term used here to embrace painting and the graphic arts.

A primary aim of the book is to come to grips with the idiosyncrasies of diverse representations of Parisian spaces, both outdoor and indoor, aglow with clairage, in order to attend closely to patterns of artistic interest and disinterest in the lights, as well as relevant routines of topographic and social inclusion and exclusion. The chapters that follow track the aesthetic results of a specific episode of passion for clairage that took hold of the city and its artists during the final quarter of the nineteenth century and the opening years of the twentieth. They investigate diverse ways that visual representations of night in the City of Light both disenchanted and reenchanted the French capital city during the era of gaslight and its coexistence and competition with new electric illuminations. This study of art from the later 1800s thus departs from custom by getting out of the sunshine to map responses to the illuminated darkness.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).