European Perspectives presents outstanding books by leading European thinkers. With both classic and contemporary works, the series aims to shape the major intellectual controversies of our day and to facilitate the tasks of historical understanding.

For a complete list of books in the series, see .

Columbia University Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support for this book provided by Publishers Circle members Paul LeClerc and Judith Ginsberg.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2021 Columbia University Press

LA VRITABLE HISTOIRE DE LA BELLE POQUE by Dominique Kalifa Librairie Artheme Fayard, 2017.

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55438-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kalifa, Dominique, author. | Emanuel, Susan, translator.

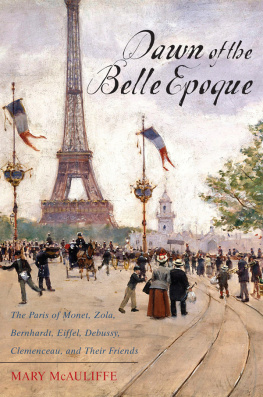

Title: The Belle poque : a cultural history, Paris and beyond / Dominique Kalifa ; translated by Susan Emanuel.

Other titles: Vritable histoire de la Belle poque. English

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2021] | Series: European perspectives: a series in social thought and cultural criticism | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020054764 (print) | LCCN 2020054765 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231202084 (hardback) | ISBN 9780231202091 (trade paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: FranceCivilization18301900. | Arts, French19th century. | Arts, French20th century. | FranceIntellectual life19th century. | FranceIntellectual life20th century. | FranceCivilization19011945. | FranceSocial life and customs19th century. | FranceSocial life and customs20th century. | FranceHistoryThird Republic, 18701940.

Classification: LCC DC33.6 .K3413 2021 (print) | LCC DC33.6 (ebook) | DDC 944.081/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020054764

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020054765

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Julia Kushnirsky

Cover image: Illustration by Henry Sene Yee after Ah! La Belle Epoque! Palace revue adapted from Andr Allehauts program on Radio-Paris

CONTENTS

- POSTSCRIPT: THE BELLE POQUE AND THE GILDED AGE,

by Venita Datta

W e all know something about the Belle poque. While the expression is somewhat impressionistic, it does evoke images familiar even to those who dont speak French. For the French, memories of school history mingle with how the era has been evoked in novels, films, and songs. The Belle poque is also a term used in art history books and exhibition catalogues. And then there are period photographs, portraits, postcards, posters, advertising, certain objects, and a thousand other little things from a past that is not that distant. Let us start from that beginning and try to sketch a portrait of an era as it emerges from our most familiar representations.

Belle poquewe must be in France, even if the expression was extended gradually to other languages and cultures, as if to signal the great hold, mainly cultural, that this nation had over the rest of the world at the time. When was that? Around 1900. We will see that the dates tend to float and that there are different versions of the time span, but 1900 is a round number, a flattering date This last point is essential: the Belle poque almost always evokes the insouciant and frivolous world of high society, the gay life of salons, worldliness, and the high life. Audiences frequented theaters, the opera, and hippodromes, and dined with champagne at Maxims; the men wore top hats and carnations in their buttonholes; the women wore hobbled skirts and gigantic hats.

Nobody was nave enough to think that this worldand the demi-monde of the great courtesans who gravitated toward itembodied the society as a whole, but people wanted to believe that the image gave that society its tone. The peace that had preserved Europe and the consequent growth and economic prosperity were indeed quite real, and the leisure and entertainment industries were in full flightall of which gave a feeling of lightness and joie de vivre, implying a universe of shared pleasures. The Belle poque was lifes festival.

Some other traits are frequently associated with this sterling picture, starting with the feeling that progress was all-powerful. We commonly see the Belle poque as positivist: the periods picture album features the marvels of science and technology. The Belle poque is incomprehensible without the scintillations of the Electricity Fairy that rolled back the frontiers of the night, without Edouard Branlys refinement of the wireless telegraph, without the work of Henri Becquerel or Marie Curie, who reinvented the physical world. This progress nourished industry and stimulated growth; it was free and nonchalant because there was no perceived downside. The optimism was expressed in the form of exploits, those of the automobile pioneers, or better still, aviation champions like Louis Blriot or Roland Garros. It triumphed in public celebrations that seemed to captivate everybody: the automobile show that opened in Paris in 1898, the inauguration of the Mtropolitain subway in July 1900, and the first aeronautics salon at the Grand Palais in 1911. The strength of both progress and technical modernity lay in their serving everybody, benefiting every citizen. The Paris Exposition (Worlds Fair) of 1900, which welcomed more than fifty million visitors to what was both a great industrial exhibition and an immense attraction park, made this Paris known to the whole world. The cinematograph (just invented by the Lumire brothers), purely a product of the machine and of industry, accomplished even more: in little more than a decade, it went from being a simple technology to a formidable entertainment spectacle, open and accessible to all, using a new international language that appeared to be an animated synthesis of all our representations and all our emotions.

We believe more eagerly that progress triumphed because it was conceived as the bearer and creator of freedom itself. Despite the persistence of large pockets of inequalities, the Belle poque imaginary (imaginaire) agreed that poverty was retreating, that manners were softening, that well-being and consumption were increasingbringing along with them a joie de vivre. This hard-won freedom, politically ensured by the Triumph of the Republic (title of a sculpture that was installed in 1899 in the Place de la Nation), was proclaimed by the French people in theaters packed to watch Edmond Rostands play