Wakefield Press

Mothers in ARMS

Meg Hale is a former social worker and government investigator who lost a child to adoption in South Australia in 1968. Working as ARMS s first social worker in the 1980s she helped South Australia pass the first laws in the English-speaking world giving mothers the right to apply for identifying information about their children. Meg continues her work as an activist, advocating for the rights of mothers in adoption.

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2014

This edition published 2014

Copyright Meg Hale, 2014

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Edited by Julia Beaven, Wakefield Press

Cover designed by Stacey Zass, Page 12 design

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Hale, Meg, author.

Title: Mothers in ARMS: forced adoptionmothers find a voice / Meg Hale.

ISBN: 978 1 74305 332 4 (ebook: epub).

Subjects:

Australian Relinquishing Mothers Society.

Association Representing Mothers Separated from their Children by Adoption.

AdoptionAustralia.

AdoptionMoral and ethical aspectsAustralia.

Mother and childAustralia.

Dewey Number: 362.7340994

To Valma Gay, who was afraid and spoke up anyway,

and

to Maureen Craig, whose energy lasted the distance.

Contents

Acronyms

AASW Australian Association of Social Workers

AMA Australian Medical Association

ARMS Australian Relinquishing Mothers Society, later known as Association Representing Mothers Separated from their children by adoption

ATOM Australian Teachers of Media

NCSMC National Council for the Single Mother and her Child

PASS Post Adoption Support Services

SPARK Single Pregnancy and After Resource Centre

WIS Womens Information Switchboard

Foreword

I have had the honour of knowing Meg for thirty-four years. We are good and close friends. Over the years we have laughed and cried, and shared our hopes and dreamsand our deepest secrets. We have raised our children, overcome relationship breakdowns, and struggled through career challenges. We have buried our parents and lost dear friends along the way. But our bond has meant more than just friendship. It has allowed me to be part of a journey, both personal and political, from sadness and despair to empowerment, realisation and truth.

We all dream about changing the world, and know the adage: It only takes one person to make a difference. But before we can start to dream we may need to change ourselves; or as Gandhi said, Be the change you want to see in the world. In Mothers in ARMS Meg writes about a very personal struggle that made a difference. It demanded courage and determination. It led her to join a group of women who had the resolve to bring about major change, not just for themselves but for the many thousands of other women who shared the injustice and stigma associated with forced adoption in Australia. When I first met Meg she described herself as a bad girl who had had her child taken from her. She wanted to check that this would not harm our friendship. She told me how a decision she had no choice about making impacted on her every day of her life. She described the overwhelming loss and sadness, and how she felt alone, angry and betrayed. These feelings never went away. She could not reconcile it. Knowing this did not harm our friendship, it strengthened it.

No one is more qualified to speak on the impact of a life-changing event than the person who experienced it. The writing of this book is the result of a healing process that has taken many years, and the changes it highlights have been significant personally and politically and impacted on many. I am proud that I have been able to share it.

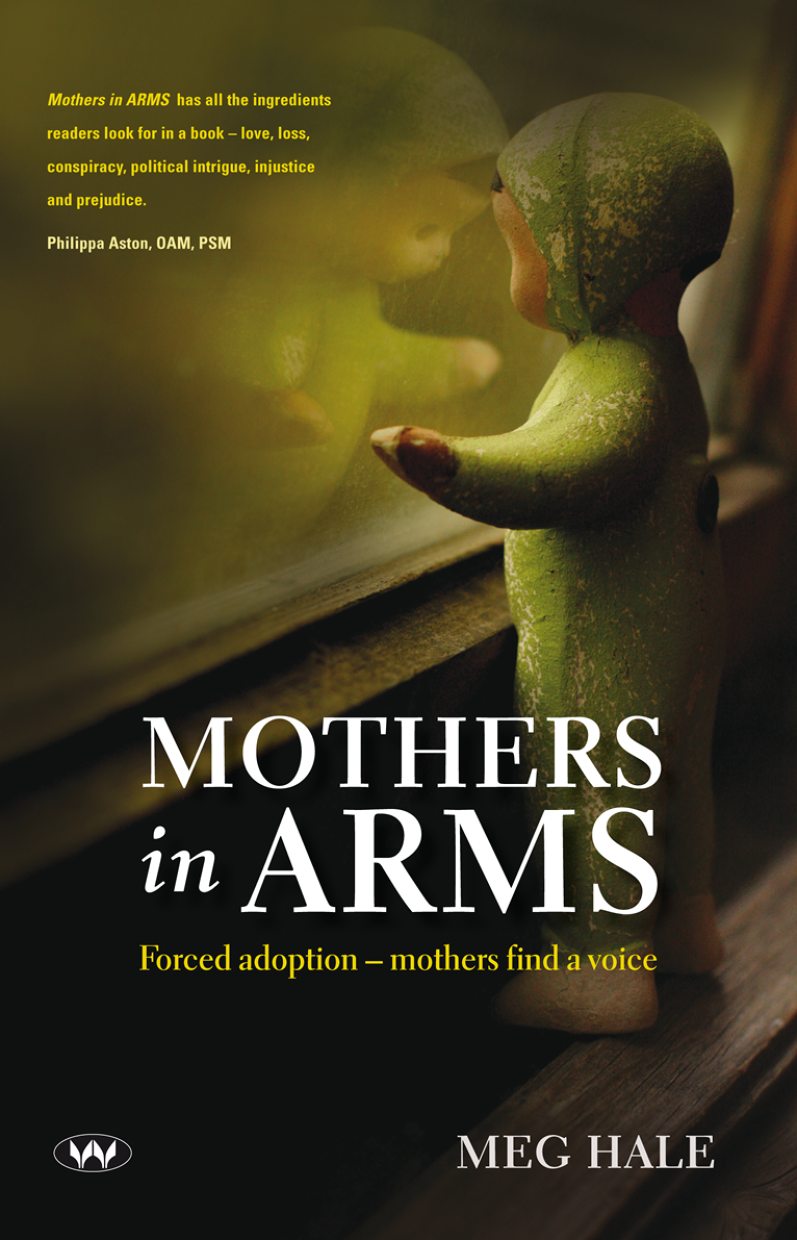

Mothers in ARMS has all the ingredients readers look for in a book. It is about love, loss, conspiracy, political intrigue, injustice and prejudice. It tells of a growing awareness and confidence to stand up and fight back, and the courage to do it. And it challenges long-held societal prejudices, revealing the bitter impact forced adoption has had on so many lives.

Philippa Aston, OAM, PSM

Prologue

1968

An antiseptic hand pushed hard against the girls chin, twisting her head to one side and pinning it into the rubber pillow. No one spoke but everyone in the delivery room knew it was to stop the girl from looking at her baby when it was born.

With her face suffocating under the weight of the nurses arm, the girl gave one last push and the baby was delivered. And as quickly as it arrived, the muffled cry of new life disappeared behind a closed door. Resigned, the new mother focused her eye on the clock on the wall and saw that her child had been born at half past two in the morning.

The hospital almoners voice was harsh and clipped as she reminded the girl that she must sign the adoption papers as soon as she left hospital. There was no point asking the almoner again why she had to give up her baby. The answer never changed. Youre not married, she would say. If you really love your baby youll do the right thing and let it be adopted by a married couple who will give it a life you would never be able to provide. It would be selfish of you to keep it.

The girl touched the tiny wrinkled hand and instinctively the fingers curled around her own, clinging tightly in some primal reflex. She stared in awe. Youve got long fingers like me, she whispered. I must remember that.

The girls head whirred as another hand pushed a Consent to Adoption form in front of her. A stiff voice said, Sign here, and it snapped when the girl asked if it were true that she had thirty days to revoke her consent.

It would be selfish of you to change your mind. The baby will be with its new parents and it would be cruel of you to take it away from people who already loved it, now wouldnt it?

The girl signed the paper and thought how ironic it was that it should be called a consent when she felt she had been forced into it from the beginning.

The girl left the grey government building and stopped when she reached the footpath. She thought about the tiny baby she had left behind and how cruel it was that she should have to give up her child simply because she was unmarried. And as she disappeared down the street and into the anonymity of the crowd she muttered under her breath, One day somebody will do something about this. This is so wrong. And quietly she added, When youre grown up, please come and find me if you can.

1

The First Voices

It was a week before Mothers Day 1982 and mothers sat among the attendees at the Third National Adoption Conference in Adelaide. The women squirmed in their seats as they heard about the adoption experience from the adoptive parents point of view and they sighed when social workers talked about the mechanics of finding parents for unwanted babies. Apart from a few comments in one of the workshops no one mentioned the mothers at all.

Next page