Prologue

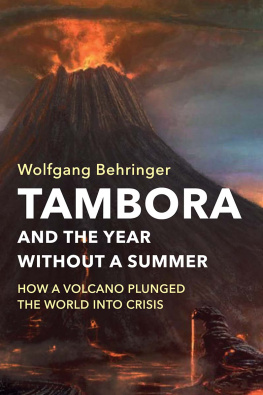

It all started two hundred years or so ago on the fifth day of April in 1815. For over five days a huge volcano named Gunung Tambora that towered over the remote island of Sumbawa in the East Indies, erupted in a spectacular fortythree kilometre high, multicolumn display of fire and smoke.

Indonesia, as the East Indies are now known, takes up a lengthy part of the Pacific Ring of Fire where volcanoes line the edges of massive tectonic plates. Hundreds of them stand in sentinel all along the shores of the Pacific Ocean like giant Viking beacons.

Indonesia is a massive country. Thousands of islands stretch for more than 5000 kilometres from West Papua in the east to Aceh on the western tip of Sumatra. There are more than one hundred and twenty volcanoes in Indonesia alone, and many are intermittently active. Somewhere in the archipelago, you can expect at least one of them to be rumbling, or even erupting, at any one time.

Most of their conniptions are small, but they still cause local disruption and a little damage. Tamboras awakening was very different indeed. The April 1815 eruption was probably the biggest eruption the earth has seen in 10,000 years. Its ash cloud spread over an area the size of Australia, blocking out the sun in many parts for several days. People waited, terrified perhaps, as they scurried from shelter to shelter in pitch black at noon in search of sustenance, friends or family. As the ash fell to earth it buried crops, collapsed roofs, and sank ships. Tens of thousands of people perished immediatelyplucked from their homes and hurled skywards by the pyroclastic winds or crushed and cooked by superheated pyroclastic flows, swept away by tsunamis, bombarded by huge lava bombs, or in the months and years after the eruption, they died a slower, equally tragic death, through disease or starvation.

But that wasnt all. Tambora pumped millions of tons of chemicals into the stratosphere and formed an aerosol blanket of sulphuric acid that covered our planet and lingered for at least three years, reflecting much of the suns heat and light back into space. The result was a cooler earth and the Year Without Summer. In postwar Europe, North America, and Asia crops failed, diseases like cholera took hold, and civil unrest grew. Millions of people had died or had been displaced, and whole populations had changed dramatically.

And here was the genesis of both Frankensteins monster and the bicycle: the continuous foul weather in Switzerland caused Mary Shelley to stay indoors where, instead of larking about in boats on Lake Geneva and whiling away the long summer evenings reading poetry, she wrote of Dr Frankenstein and his monster, arguably the first science fiction novel the world had ever seen. At the same time in Germany, as horses starved around them because the weather was too inclement to grow hay, two enterprising young men invented the first bicycle. Both were products of Tambora.

As a resident of Sumbawas neighbouring island of Lombok, I had long been intrigued and drawn to this island, and the mountain that had such a wide and dramatic effect on our planet. So, with the bicentenary of the eruption looming, I took a number of trips by motorcycle through Sumbawa to see what life is like in modern day Indonesia, explore for myself the island, and climb the mountain that had changed the world.

I met tiny, yet experienced race jockeys the same age as my preschooler son and an aged princess who is a direct descendent of the Rajah of Bima who was ruling at the time of the eruption; I visited mining towns, surf camps, and the small island of Bungin whose residents claim they live on the most densely populated island in the world and whose goats are rumoured to survive eating nothing but plastic and rags. Everywhere I went Tambora was omnipresent, like a school bully leering over my shoulder. And when, at last, I climbed to its crater rim, stared out across a hole seven kilometres in diameter and a nearly a kilometre deep, and smelled its sulphurous fumes, I was in awe. Tambora is an extreme mountain in every way. Huge gas plumes regularly burst from vents far below where I stood on the precipice, and the continuous crashing of rocksfalling and echoing around the craters cliffsgave me a feeling that this mountain is still very much alive and just biding its time.

Then, looking east to Sangeang Api, west to Rinjani on Lombok, and further to Agung on Bali, I realised that any of these huge volcanoes, which stand in line like giant boils along the archipelago, could take their turn and release their fury on our planet, just like Tambora did two hundred years ago. Standing on the summit, I wondered if we would be prepared. Now, writing safely in my home, I still doubt that we would be.

Chapter 1.

A Destination Just Missed

From the deck of the Antares, Tambora looked enormous but flatmore like a giant upturned pie than the classic volcano. The mountain was purple in shadow, out of focus through the early morning November haze.

Wed been on the Antares for a few days after leaving Teluk Nara, in North West Lombok. Fabien, owner and captain of this small charter yacht, was humming in the galley where daily he would create bread masterpieces that stereotypically tagged him as being a Frenchman and proud of it.

This was my third trip in waters close to Tambora. Several years before I had taken a tourist boat through the Flores Sea from Komodo to Lombok and for two days had cruised past the mountain off its northern coast, stopping twice along the way: firstly at a boat building village and then at the small island and wildlife reserve of Moyo to see the waterfalls. Tambora was calling like a siren as we passed, a destination just missed; a place I wanted to see.

I had had a second near miss, also travelling on the Antares, when we passed by on a diving trip to Komodo National Park, and the surly siren of Tambora had again called me to attend her, to no avail.

Then, on this third trip, I had tagged along with Mark Heyward and his sons with our host, Andrew, all friends and neighbours in Lombok. Andrew is an agronomist, who was seeking new areas to grow tobacco and trees, and pairing a yacht with a motorbike seemed the perfect way for him to get into remote parts of Sumbawa. Mark and I had jumped at the chance to travel with him, and at the last minute, he had agreed that Mark could bring his two boys, Rory (11) and Harry (8).

Before breakfast, Rory and I were sitting on the cabin roof watching the sea slide past. The boys had both tried SCUBA diving the day before off Moyo Island and were agog at the new world that had opened up to them. I was trying to get Rory interested in Mount Tambora.

Two hundred years ago, if you were diving here, youd have found nearly everything in the sea dead. The land was dead too. Look at Tamborasee how its flat on top? It used to be shaped like a proper conemore like Rinjani in Lombok or Agung in Bali but bigger. It was four thousand three hundred metres high, but in 1815, it blew up in what people say was the loudest noise ever heard, and it lost its top. That was nearly 200 years ago. Millions of tons of rock and dust were blown up. Can you imagine what that would have been like?

I guess you wouldnt want to be in this boat here when that happened, said Rory.

Youre right. There were tsunamis and enormous floating islands of pumiceyou know that rock that floats? Boats werent much good to you then. It caused what they called the Year Without Summer in the northern hemisphereEurope and America froze, and they couldnt grow food, so people starvedand not just for one year as the volcanic winter lasted at least three years. In India and China, the monsoon never arrived, so they had no food there either. There was civil unrest and riots, and thousands of people moved or emigrated as climate refugees. In America they used to call the year eighteen hundred and froze to death. Oh, and Frankensteins monster was born.