Praise for Phill Braggs latest book.

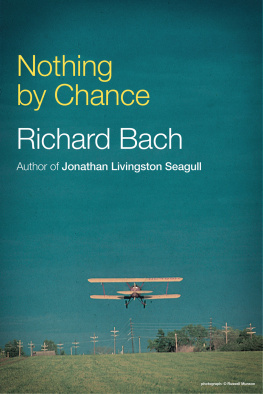

Phill Bragg's Needle, Ball, and Alcohol has me itching to take the front seat of his antique biplaneprovided he is flying of course! He beautifully captures his passion for his vintage World War II trainer, the people he encounters, and the adventure of travel with a curious nature, a love of history, and a self-deprecating sense of humor that keeps the reader turning pages. Such an interesting, fun read!

Becky S. Ramsey

Author of French By Heart: An American Familys Adventures in La Belle France.

Phill Braggs book, Needle, Ball, and Alcohol, takes you on a cross-country trip in an old open-cockpit biplane. As you read youll experience the trip as if you are along in the front cockpit. He writes down all the right things to make you love the journeythe seeing rivers and roads, the smelling trees and earth, the feel of smooth morning air. You will understand what flying was like when it required not a computer, but a pilots eyes, ears, and soul. Bragg knows how to make you feel the exhilaration of it all. And he loves his old, beautiful aircraft almost as much as he loves his mama.

Clyde Edgerton

Author of The Floatplane Notebooks and Solo, My Adventures in the Air

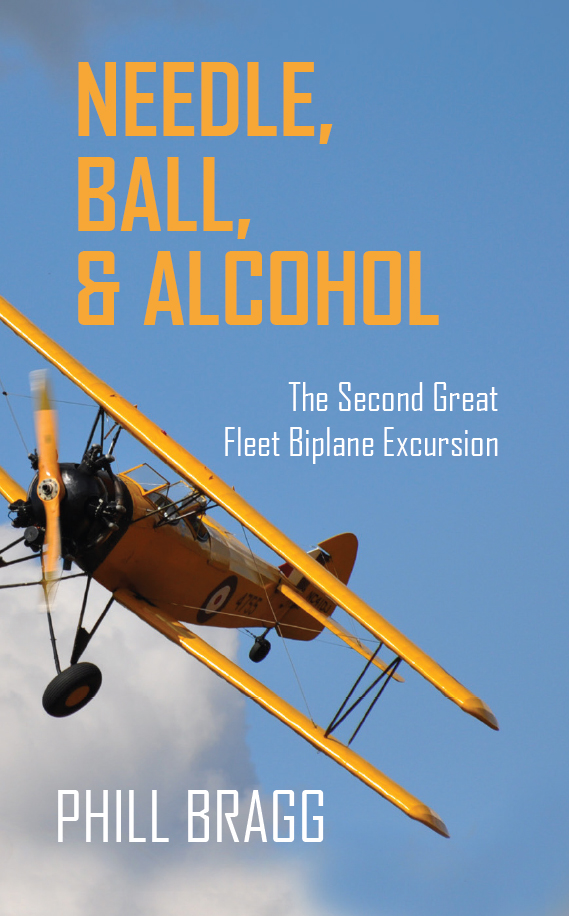

Needle, Ball, & Alcohol

Published by

Clouds Ive Known Publishing Co.

www.cloudsiveknownpublishing.com

Copyright 2014 by Clouds Ive Known Publishing Co.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

ISBN: 978-0-9906863-1-6

Printed in the United States of America

Mira Digital Publishing

Chesterfield, MO 63005

To my wife, without whom I would never have owned an old biplane.

CHAPTER ONE

A THREE-TERM SHERIFF UP in Franklin County once told me that banjos have souls; he had shown me the way of the claw hammer banjo and he said banjos were special, not like guitars or even fiddles. After flying airplanes for more than thirty years, I know that airplanes have souls too. They are not like cars or boats; they are ever so special. But especially the old ones.

When I was twenty years old and a very inexperienced pilot, I read of a place east of Wichita where you could land on grass and taxi on the public street to an old hotel and eat lunch. I told myself I would go there and that I would do it only in an open-cockpit biplane. Thirty-four years later I bought a 1941 Fleet Model 16B, restored lovingly over a decade by an old-school aeronautical engineer from the days of slide rules and giant drafting tables.

He sold it to me, a complete stranger, because a mutual friend had told him I wanted to fly that airplane all across the United States. He did not want to see it only pulled out of a hangar on calm Sunday afternoons for a couple of circuits around the patch. He wanted that airplane to travel and to be seen and enjoyed by those who would know why to appreciate it. Sadly, he would not live to see pictures of the Fleet parked proudly beside a Rocky Mountain trout stream or on the Kansas prairie. But the Fleet would do those things and more.

This was not the Fleets first adventure, but it was the one which finally took me to Beaumont, where I could taxi up to the old hotel. My friend, Wayland, went with me. He loves road trips and will endure any mode of travel and any of its inconveniences just to detour in order to see the worlds largest acorn or the worlds biggest hand-dug well. He is an intrepid traveler who believes in the journey as much as the destination. So, to be in my front cockpit was almost inconsequential to Wayland. If I had told him I was driving out to the Midwest on an old riding lawnmower, he would have been right there sitting on it somehow. For me though, it had to be in an antique, open-cockpit biplane. I believe in the journey as much as the destination too, but for me, seeing America from the rear seat of the Fleet is the destination. It is both. It is a dream I have dreamed since I was twenty years old reading about grass strips and the little mom-and-pop cafes that sat beside the airfields. Many of these establishments have disappeared during the three decades it took me to finally buy an old biplane, but some are still out there if you search for them.

Beyond Beaumont though was Greensburg, Kansas, which would be our westernmost point of landing and was originally the motivation for our excursion. We had met much of the towns population several years before under somewhat tragic circumstances and we wanted to return for a visit.

CHAPTER TWO

OUR DEPARTURE WAS DELAYED for a whole year because I had to remove my center section fuel tank for a repair. The tank was easily fixed but the resulting fabric repair was huge and I am the slowest airplane mechanic in the world, especially when I am learning a new art. I was learning the mysterious ways of dope and fabric and the curve was a long, high one. But it was as much a part of the upcoming journey as any other aspect of the trip; it was showing the Fleet that I wanted to understand it and care for it. The shame of it was that my dad had tried to teach me these things when I was a teenager and he was busy keeping two Piper Pawnee crop dusters in the air. But I cared more about watching television after school than helping him replace cylinders or rib stitch out at the grass strip where he flew. No childhood was more wasted.

Better late than never though and there I was all last summer using his old EAA dope and fabric manuals, still in mint condition, trying to unravel the secrets of seine knots and why butyrate sticks to nitrate but not the other way around. By OctoberI said I was slowthe job was completed. My big fabric repair turned out okay and passed muster for the Fleets annual inspection, but I was glad it was on the top wing and mostly out of sight. You never knew when one of those Oshkosh Grand Champion craftsmen was going to wander out of a hangar at some obscure little airport while you were pumping gas and take a really close look.

There was one other repair that had to be made as well. I had replaced a copper head gasket only twenty flying hours previously and it had ruptured again. I had landed after returning from Ball Fields thirty-ninth annual fly-in and immediately heard the steam-hissing sound coming from the number four cylinder. There was much more to be learned about this seemingly straightforward repair. Through Al Balls (no relation to the Ball Field gang) generous giving of his encyclopedic knowledge of the Kinner engine, I learned that I must anneal the copper gasket with my torch, which made it pliable and better able to seal the space between cylinder head and barrel. There was also a procedure to properly break in the new gasket and re-torque the cylinder nuts once I flew the airplane again.

Howsoever cautious and wary I may be with needle and thread and nitrate dope, I am a thousand times more careful when I am working on an engine. My normal snails pace is even slower than usual in order to avoid mistakes. I did not grow up disassembling and reassembling my toys like some kids. I watched television. And while that garnered me a certain kind of knowledge, it did not teach me to time magnetos or to weld aircraft tubing. But one habit I had somehow inherited from my dad was to read manuals and to do things pursuant to the manufacturers instructions. He was a firm believer in that; he detested shade tree mechanics.

Next page