The Cannibal Queen

Stephen Coonts

For Rachael, Lara and David

Contents

Oh, that I had wings like a dove, for then would I fly away, and be at rest.

Psalms 55:6

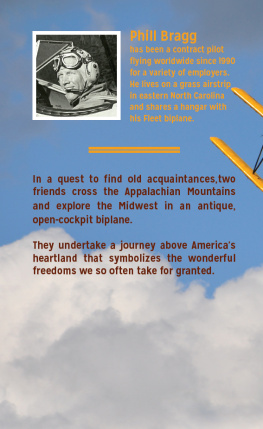

A LL REALLY GREAT FLYING ADVENTURES BEGIN AT DAWNTHE dawn patrol, takeoff from Roosevelt Field for the flight across the Atlantic to Paris, launch at first light for a strike on Rabaul, and so on. Unfortunately this adventure was scheduled to begin at noon. It actually got under way at 1:35 P.M. on a clear, sunny Saturday afternoon in June, late, as most things in my life are.

That was what my watch read when I took a deep breath and looked at the top of my sons head in the front cockpit of the Stearman. Our few bags, a laptop computer and a camera bag were stuffed into the luggage bay aft of the rear seat. The coffeepot at home was off.

For the next three months I would be flying this 1942 Stearman open-cockpit biplane around the United States. I had shamelessly maneuvered my publisher into buying a book about this adventure, and now it was time. Time to fly.

David, age fourteen, had agreed to accompany me for the first two weeks, as far as Disney World in Orlando. He had never been there so he agreed to go with the pilgrims enthusiasm.

The plane was fueled, I had checked everything personally, sectional charts were ready at hand, the sky looked good, my ex-wife, Nancy, and our two daughters were on hand to wish the adventurers a safe journey, the usual photos had been snapped, I had signed a new will at my lawyers three days previous What else?

John Weisbart, the guy who taught me how to fly the Stearman, is also on hand. You checked everything? he calls.

Yeah.

The oil dipstick cap? David asks.

Yep. Even that. I had forgotten to reinstall it on one previous flight with David. Oil sloshed all over the left side of the plane on landing.

Clear, I call, flip on the master switch and engage the starter. The long prop swings. Six blades, then the mag switch to both. The big radial engine coughs out a gray cloud of oil, then catches with a throaty rumble.

With oil pressure up and the mixture knob and throttle retarded to idle, I reach for my helmet and headset and pull them on. As I am fumbling with the chin strap Davids mother, Nancy, runs over to the side of the plane, kisses her fingers, then touches her fingers to my lips. It is a wonderful gesture.

With waves to everyone, we taxi out. After a few minutes of warming the engine and running it up, we taxi onto the runway and add power. The engine responds willingly. As I lift the tail off the runway I glance at the gauges23 inches of manifold pressure and 2,250 RPM, which represents full power at 5,300 feet above sea level, the field elevation here in Boulder, Colorado.

I pull her nose off at 65 miles per hour and we are flying. She accelerates to 75 and I ease the stick back to hold that airspeed. Up we go at about 300 feet per minute.

We turn downwind and sail along parallel to the runway at 800 feet above the ground. Now the base leg, throttle back like we were going to land, then final but offset right. I level off a hundred feet above the ground and shove the throttle forward to the stop. Nancy and the girls are waving as we swoop overhead with the engine roaring mightily. I love that song.

We head east. First stop will be St. Francis, Kansas, the ninth annual Stearman fly-in, which by happy chance is this weekend, the second weekend in June. Level at cruising power at 7,500 feet and properly trimmed, David wants to fly her. I turn the stick over to him and search the sky for other traffic as I try to put it all into perspective.

Were on our way, I tell him.

He soon gives the plane back to me. I gently waggle the stick and rudder and think of all the scheming and errands and planning that went into this aerial odyssey. This will be three months of flying around the country, three months of writing about it. The product will be my fifth book, and probably the most difficult one of the bunch. The flying will be the easy part.

Dave and I talk nervously on the intercom about this and that, pointing out landmarks, other airplanes, just talking. Finally we calm down and watch the land roll by beneath us.

The engine is humming perfectly. I sit drinking in the yellow wings against the blue sky and green land.

The planes a big yellow Stearman open-cockpit biplane, a primary flight trainer built in the summer of 1942 by Boeing in Wichita, Kansas, for the Royal Canadian Air Force, one of three hundred built that summer for the Canadians under Lend-Lease. Like most Stearmans, when delivered this bird wore a 220-horsepower Continental engine, a big round radial.

The Canadians returned their Stearmans to the U.S. Army that fall. Apparently the rigors of open-cockpit flying in the Canadian winter were more than dedicated flight instructors and students could endure, even for king and country. So this beauty served out the remainder of the war in American colors.

After the war she was sold as surplus for $500 and acquired civil registration number N58700. Two owners later she was flying in Washington state for the Atomic Energy Commission. Why the AEC needed a Stearman is a mystery that will probably never be solved.

After that second tour of government service this plane was once again declared surplus and joined thousands of her sisters flying the American plains as a crop duster, then a sprayer as chemical technology changed. There she flew for over thirty years as the decades rolled by, the 1950s, the 60s, the 70s, and into the 80s.

Ready for the scrap yard in 1987, N58700 was purchased by Robert Henley, an airplane enthusiast from Denver, and restored by his father, Skid Henley, in McAlester, Oklahoma. Skid installed a 300-horsepower Lycoming R-680 engine in the old girl, one that still wears a plate that notes that the U.S. government accepted delivery of this engine on August 2, 1942. So engine and plane are of equivalent age.

Restoring N58700 was obviously a labor of love. Skid gave her new threads of Stits fabric and painted her yellow. He added a gorgeous brown accent stripe that circles the lip of the cowlinghe installed a cowling because he liked the look of itand runs the length of the fuselage on both sides. The workmanship is superb throughout.

In May 1990 the thought occurred to Robert Henley that he had too many toys. The fact that he is a family man may have been a factor. Temporarily insane with this delusion, he showed me his Stearman. It was lust at first sight.

She was sitting primly in a tee-hangar at Front Range Airport, east of Denver. Standing in the sun and looking into the darkness of the hangar, you saw the yellow and the wings and the gleaming metal prop.

We rolled her out into the sun as Roberts wife, Ann, told me how they had worked all morning washing and waxing.

The sunlight on that yellow fabric was physically and emotionally overpowering, so brilliant, so bright, so beautiful. I stood there awed as a gentle breeze played across her and stirred the ailerons. She was big, yellow all over and greasy and oily in all the right places. She reeked of those wondrous smells that promise flight.

Stroking that taut yellow fabric, caressing the voluptuous, sensuous curves, sitting in the cockpit and staring at the motionless instruments and waggling the stick of laminated hickory as I ran my fingers along the throttle and mixture and propeller control levers, I fell madly in love.

The engine ah, that big, round nine-cylinder radial is a work of art, its crankcase a battleship gray, the perfect background to display that engine placard that so proudly proclaims 1942. Not a fleck of rust anywhere. A film of oil on the pushrod bushings and on the bottom of the cowling. That morning thirteen months ago I reached in and got some on my fingers and felt that feeling of good, clean oil against precision-machined steel.

Next page