Dedicated to

Mom, Dad, and my brothers and sisters

And to

Sarah, Leah, Ben, and Mom

1

T HE C HASE I S O N

As I stood there on that unusually warm November morning, looking all around me, everything seemed to say New York.

I was a row or so back from the starting line of the 2005 New York City Marathon, with the Manhattan skyline, shrouded in a dank, soupy fog, rising off in the distance beyond New York Harbor. Nearby, my teammates, 150 or so New York City firefighters, were doing their final stretches and giving each other one last command: Beat the cops, okay, beat the NYPD. Any second, Frank Sinatra would be blaring over the loudspeakers, so that every last one of the 37,597 runners about to take off from Staten Island via the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge for a 26.2-mile race through the citys four other boroughs could hearwhat else?New York, New York.

Like I said, everything seemed to say New York.

But all I could think about was Boston.

Boston? What had gotten into me? I was a New Yorker, born and raised in Brooklyn, with the accent to prove it. When I used to have hair, I combed it like Tony Manero, John Travoltas character in Saturday Night Fever; my sisters, Eileen and Maureen, called me John Revolting. Now I lived in midtown Manhattan, where I was a firefighter with Ladder Company 43 in East Harlem, and on this marathon day, to remember all my fellow firefighters who died on September 11, 2001, I had stenciled 343 on my left arm. I also owned three bars in Manhattan, and if needed I could tell you where to go for the best Manhattan clam chowder, Brooklyn lager, or New York strip in the city. I had nothing against Bostonin fact, I was a huge Bill Buckner fan, and Id have a beer with Denis Leary any day of the week. But New York was my town.

Still, at that moment I couldnt get that other city out of my mind.

Hey, Matty? Matty? How you feeling?

Shane, Im good, bro. Im good. How about you?

Im ready. Just keep the pace, Matty, keep the pace.

To me it sounded like Shane McKeon, a training partner and another firefighter on the starting line, was saying, Keep the faith. In a way, he was. He was reminding me to stay steady. Keep the pace. If I could click off 26.2 miles at a pace of about seven minutes and 15 seconds per mile, that would get me to the finish line in Central Park in three hours and 10 minutes. And that would easily beat my best-ever marathon time by nearly 40 minutes. And, if everything went right, that would give me a shot at finishing among the top 10 firefighters running on this day, which would help us in our annual race-within-a-race against the police department.And best of all, that would win me a prized spot in next years Boston Marathon.

And thats why I had Beantown on the brain. I wanted to run the most famous race of all. Boston.

Theyve been staging the Boston Marathon every April since 1897, and for most of those years only a select crowd gets to take part. To earn an official race entry, you need to nail a pretty demanding time based on your age. So, at 39, I had to run a 3:15 marathon. Boston race officials allow a 59-second grace period, but not a second more. I didnt want to chance a close call, so a few weeks earlier I told Shane that I would go out a bit fasterId aim for a 3:10 finish, giving myself a five-minute cushion.

Whatever it took to make it to Boston, I was game.

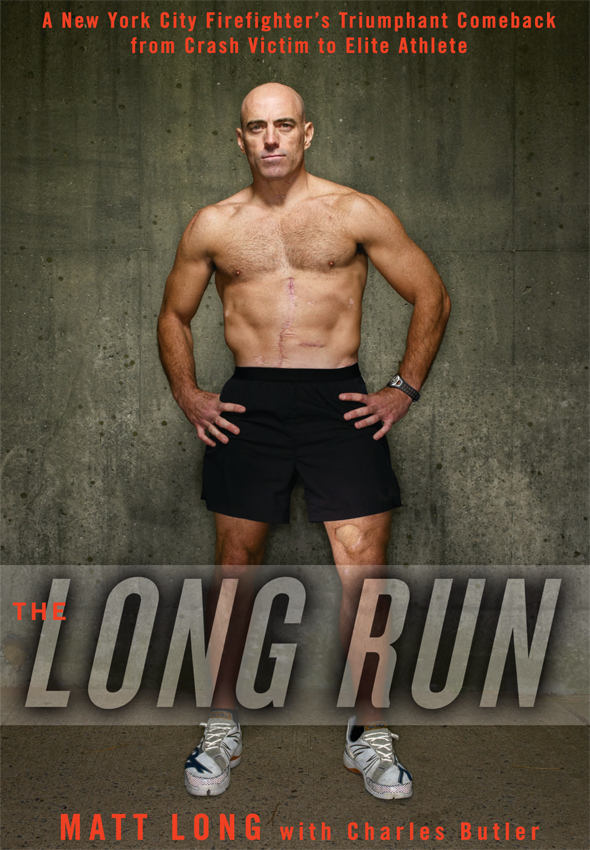

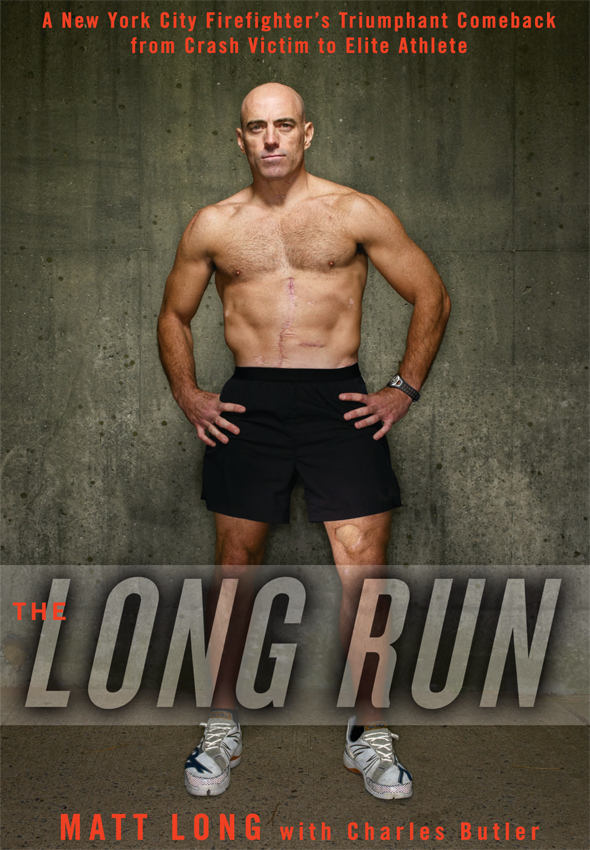

Still, even with my plan in place I knew there were no guarantees when it came to a race like a marathon. The days weather could trip you up, and todays temperatures were expected to rise to the mid-60s, scorching for late fall. I also worried that I might feel flat after so many weeks of intense training; I had been running upwards of 50 miles a week since May. And then there was the fact that I was still relatively new to the competitive running scene. Just two years ago I was a firefighter with a sore back and a triple chin; without really noticing, I had packed an extra 35 pounds on my five-foot-ten frame. I was up to 212 pounds, and behind my aching back friends were calling me Beer Belly Matty and Fatty Long. But then I found religionor I should say running, as well as biking and swimming. In other words, I found the world of triathlons.

Egged on by my friend Noel Flynn, I trained through the winter of 2004 for my first triathlona 1.5-kilometer swim, 40-kilometer bike, and 10-kilometer runthat spring. When I completed it, I couldnt wait for the next one. And the one after that. I got addicted to the competition and the training and the camaraderie among the athletes I met at different events. I joined a triathlon club. I tracked my mile-split times and my heart rate after every workout. I logged the number of miles I put on my running shoes, retiring a pair when it hit 300. I consumed nutrition books. I started preaching that bagels are not your friends at family parties. I cut back on my beer intakea huge concession for a guy who owns bars. And I started racing every chance I could. In 2004, my first full year of training, I did 14 triathlons of different lengths, and traveled everywhere from Long Island to New Jersey to Texas to do them. The adrenaline rush from the training and the competing was like nothing I had ever experiencedexcept maybe the rush of running to a fire with my ladder company. And all the work paid off in other ways as well: I dropped to 175 pounds, and the backache disappeared for good. Suddenly, I was in the best shape of my life.

Then I made the ultimate commitment: I signed up for an Ironman, an event that can make waste of even the best athlete over the course of a 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike, and 26.2-mile run. It was in Lake Placid, New York, in July 2005, four months before the New York City Marathon. My training buddies thought I was nuts. Matty, whats the rush? Frank Carino, a close friend and fellow firefighter, asked one day after we did a long, hard training run together. Frank had attempted his first Ironman only after competing in smaller ones for five years. The Ironman can take a huge toll on your body. You can build up slowly, you know.

Frank, I know, but the thing is, I love this stuffeven when it hurts.

No, there was no talking me out of it. On July 26 I did my first Ironman, finishing in 11 hours and 18 minutes, and in 279th place out of about 2,000 finishers. I did the marathon legthe third and final onein three hours and 44 minutes, nearly nine minutes faster than my last solo marathon seven years earlier. A pretty good showing, I thought. Pretty good? Frank said after we were done. That was fantastic. Matty, youve got to slow down, youre catching up to me. Youre definitely going to Kona someday.

He was talking about Kona, Hawaii, site of the annual Ironman World Championship. Frank had qualified for the first time with his race in Lake Placid. For me, Kona would be a goal come 2006. First, I had to make it to Boston.

I looked at my watch: 10:09 a.m. One minute until the cannon blast to start the marathon. Just then, John McLaughlin, an FDNY lieutenant who once ran this race in well under three hours, shouted to me.

Hey, Matt, what are you looking to do today?

Three-ten, John, I shouted back.

Three-ten. Sounds good to me. Why dont you run with me?

Next page