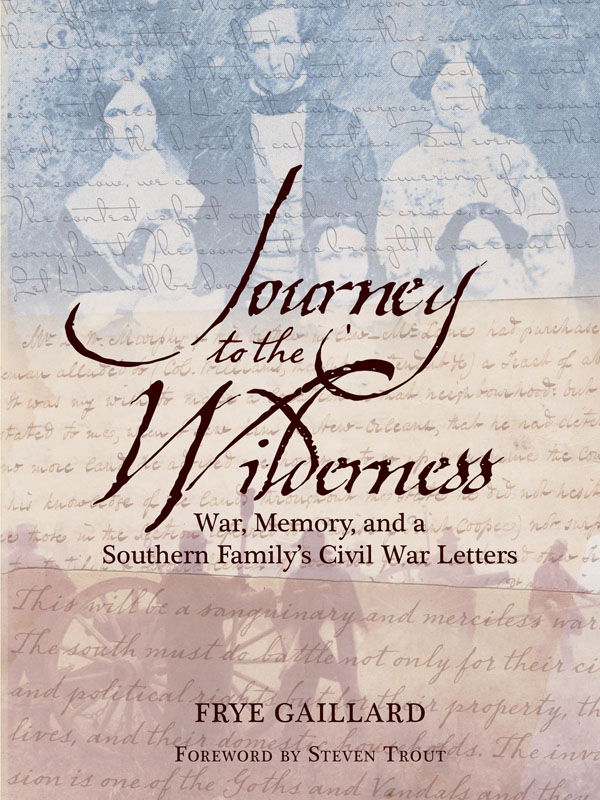

Journey to the Wilderness

War, Memory, and a Southern Familys Civil War Letters

Frye Gaillard

Foreword by Steven Trout

N EW S OUTH B OOKS

Montgomery

Also by Frye Gaillard

Nonfiction

Watermelon Wine (1978)

Race, Rock & Religion (1982)

The Catawba River (1983)

The Dream Long Deferred (1988)

Southern Voices: Profiles and Other Stories (1991)

Kyle at 200 M.P.H. (1993)

Lessons from the Big House (1994)

The Way We See It ( with Rachel Gaillard , 1995)

If I Were a Carpenter (1996)

The Heart of Dixie: Southern Rebels, Renegades and Heroes (1996)

Voices from the Attic (1997)

Mobile and the Eastern Shore ( with Nancy and Tracy Gaillard , 1997)

As Long As the Waters Flow ( with photos by Carolyn DeMeritt , 1998)

The 521 All-Stars ( with photos by Byron Baldwin , 1999)

The Greensboro Four: Civil Rights Pioneers (2001)

Cradle of Freedom (2004)

Prophet from Plains: Jimmy Carter and His Legacy (2007)

In the Path of the Storms ( with Sheila Hagler, Peggy Denniston , 2008)

With Music and Justice for All (2008)

Alabamas Civil Rights Trail (2010)

The Books That Mattered: A Readers Memoir (2013)

Fiction

The Secret Diary of Mikhail Gorbachev (1990)

Childrens

Spacechimp: NASAs Ape in Space ( with Melinda Farbman , 2000)

NewSouth Books

105 S. Court Street

Montgomery, AL 36104

Copyright 2015 by Frye Gaillard. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by NewSouth Books, a division of NewSouth, Inc., Montgomery, Alabama.

ISBN: 978-1-58838-312-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60306-361-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014957409

Visit www.newsouthbooks.com

To the family of Colonel Fred E. Gaillard

for preserving the letters of Franklin Gaillard,

our eloquent ancestor in common;

and to my aunt, Mary Gaillard,

and my grandfather, S. P. Gaillard,

who taught me that history is a living thing

Contents

Foreword

A Journey to the Wilderness... and to Fort Blakely

Steven Trout

Some years ago, the History Channel offered a disturbing glimpse of what it must really have been like to fight in the American Civil War: as part of a documentary on the battle of Antietam, a team of artillery enthusiasts set up rows of oil drums, filled them with water mixed with red food coloring, and then fired at them with actual cannons from the 1860s. The results were, to put it mildly, dramatic. Travelling at over a thousand miles per hour, twelve-pound cannon balls ripped some of the containers in half, sent others tumbling end over end, and splattered scarlet liquid twenty feet or more into the air. And bear in mind that these were metal drums, not fragile vessels made of flesh.

Realizing what artillery projectiles could doto say nothing of small-arms ammunition like the ubiquitous minie ball, which flattened upon impact, shattering bones in the processwas just one facet of what Civil War soldiers meant when they referred to the experience of combat as seeing the elephant. The sights and sounds of battle were so overwhelming and hallucinatory, so incomprehensibly at odds with ordinary experience, that only a circus metaphor would do. You had either seen the elephant or you hadnt. There was no use in describing.

So, after the war, most veterans didnt try. On both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line, a kind of Victorian grand eloquence, far removed from the terror and brutality of combat, became the signature language of the wars memory. Organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which played a leading role in Southern war commemoration, celebrated the conflict as a time of honor and gallantry, a word that still floated in the humid air of Mobile, Alabama, nearly a century later, forming part of Frye Gaillards childhood. Thousands of books on the Civil War appeared before 1900. But only a few, such as Horace Porters surprisingly graphic Campaigning with Grant or Stephen Cranes The Red Badge of Courage (written, ironically enough, by a non-veteran born in 1871), come close to preparing a present-day reader for that gruesome oil-drum demonstration.

The ground where the Blue and the Gray once clashed likewise gives little indication of the wars terrible realities. In the late 1800sas white Northerners and Southerners settled into a comfortable state of reconciliation, tacitly agreeing to the continued subjugation of black Americansthe five Civil War sites of Antietam, Chickamauga-Chattanooga, Gettysburg, Shiloh, and Vicksburg became the nations first official battlefield parks. Dotted with stirring memorials and markers, these places of remembrance (or is it forgetting?) remain among the loveliest spots in the United States, manicured green spaces whose beauty and peacefulness belie the violence that inspired their preservation.

And when legions of so-called reenactors periodically gather on these hallowed grounds, the resulting spectacle hides more of the true face of war than it reveals, a fact for which both the reenactors and their audience should be grateful. The clouds of black-powder smoke and the thunderous discharge of weapons are presumably realistic enough. But the playacting leaves out the very things that make war war the bowel-loosening fear, the rage, the confusion, and, of course, the blood. Reenacting may have its virtues, but it hardly offers a glimpse of the elephant.

In his thoughtful presentation of the family letters in this volume, Frye Gaillard reminds us that the Civil War, like all wars, was brutal and ugly. In his own way, he points a cannon at some oil drums. Readers quickly realize that the books title Journey to the Wilderness holds a double meaning. Arranged chronologically, the letters carry us from the opening of the rebellion, which most (but not all) of Fryes Southern ancestors welcomed, to the terrible Battle of the Wilderness in 1864, where the Gaillard familys most zealous Confederate met his end. But the book also journeys backwards in time, as Frye peels away layers of cultural myth and family legend to expose long-hidden pain, ambivalence, and horror. This foreword briefly considers what a journey to the Wilderness means in terms of military historyor, stated more baldly, the history of organized killing. And then it will turn to a more obscure corner of the conflict, one that nevertheless had an important place in the Gaillard familys wartime experience.

Of course, Americans dont like to dwell on the violence and brutality of the Civil Warstrangely, our most beloved warand have assiduously avoided doing so for much of the past 150 years. We prefer romance and reenactments. As Frye makes clear, in the mid-twentieth-century Alabama of his youth one could not speak of the events of 1861 to 1865 without kneeling before the conviction that the Confederacy lost the war, yes, but lost it gloriously . Within this framework of consolatory myth, known as the Lost Cause, ordinary rebel soldiers fought with superhuman endurance and resolvecertainly never running from the enemy!and were led by commanders who epitomized strategic brilliance and, of course, gallantry. By the 1950s, Lee, Jackson, Stuart, Mosby, and Forrestthe vaunted pantheon of Confederate generalshiphad all acquired cult followings, which to some extent they still enjoy today, as heroic underdogs who consistently outmaneuvered their adversaries, but whose valiant efforts were doomed by Yankee industrialism and superior numbers.

Cast in the romantic terms of the Lost Cause, the rebellion assumed a reckless grandeur. But missing from the picture was the very thing that gave this body of myth its urgencynamely, the utter, annihilating destruction that the conflict visited upon the Confederacy. Indeed, for the American South, the war was by any measure an unmitigated disaster. Nearly one in four Confederate soldiersan estimated 300,000died either from combat or disease, a catastrophe that left its mark, in one way or another, on nearly every household in the Confederate states. But the loss of so many young men was only part of it. By the time of Lees surrender at Appomattox, the regions central railroads had been destroyed, their rails creatively corkscrewed around trees and telegraph poles; its population reduced to a state of semi-starvation; and its major cities left in smoldering ruin. Photographs of Richmond, Atlanta, or Charleston in 1865 look shockingly like images of Dresden, Berlin, or Hiroshima in 1945.