Table of Contents

ALSO BY JOHN C. SKIPPER

AND FROM MCFARLAND

The Cubs Win the Pennant! Charlie Grimm, the

Billy Goat Curse, and the 1945 World Series Run (2004)

A Biographical Dictionary of Major League Baseball Managers (2003)

A Biographical Dictionary of the Baseball Hall of Fame (2000)

Take Me Out to the Cubs Game: 35 Former Ballplayers Speak of Losing at Wrigley (2000)

Umpires: Classic Baseball Stories from the Men Who Made the Calls (1997)

Inside Pitch: A Closer Look at Classic Baseball Moments (1996)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Skipper, John C., 1945

Wicked curve : the life and troubled times of Grover Cleveland Alexander / John C. Skipper.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7864-2412-5

1. Alexander, Grover Cleveland, 18871950. 2. Baseball playersUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

GV865.A33S45 2006

796.357092dc22 2006012641

[B]

British Library cataloguing data are available

2006 John C. Skipper. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

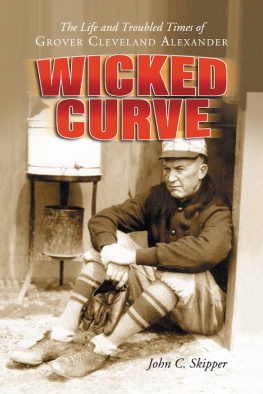

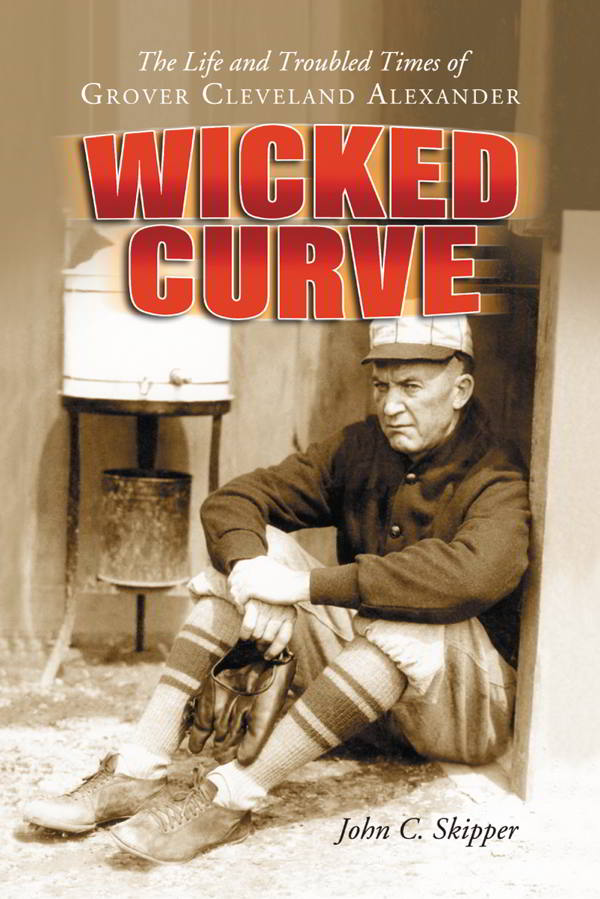

Cover photograph: Alexander sits alone next to the water cooler late in his career (Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface

Grover Cleveland Alexanders story spreads across several landscapes of the human experience. His is the small town boy makes good story, a boy who grew up in St. Paul, Nebraska, husking corn and throwing stones across the farmyard at trees, fence posts and an occasional chicken with startling accuracy. It is the story of a young man who almost got passed up in his first try for the big leagues and then set a National League record for wins by a rookie (28) that still stands, nearly a century later.

It is the story of a man who left his career behind for one year so that he could serve his country in the war to end all wars, only to come back with illnesses and demons that plagued him for the rest of his life. And finally, it is a love story between Grover and his beloved Aimee, who married and divorced him twice because she discovered that while she was better off if she quit living with him, she could not bring herself to quit loving him. And he expressed his love for her through the day he died, literally.

In this work, the authors intention is to capture the essence of a man whose passion and talent helped him rise to become one of the greatest pitchers of his or any other era and whose weaknesses brought him tumbling down. It is a story that is a matrix where inevitably the lines of triumph and tragedy meet. Every effort is made to inform with facts rather than to influence with speculation.

In that light, it is important to establish some points of clarification. The woman Alexander married (twice) was Amy Arrant. Early in her adult life, she began spelling her first name as Aimee. For consistency, that is how her name is spelled throughout this book. When Alexander was growing up, his nickname was Dode. He was also called Alex and Alec. When he joined the Philadelphia Phillies in 1911, the ballclub had a player with the nickname of Dode, so that nickname for Alex didnt stick except with the folks back home. He is best known by the nickname Ol Pete, for which there are two possible reasons. It is said that when he was a young ballplayer, he went on a hunting trip in the off-season and fell off a buckboard into some peat moss. Those who were with him started calling him Ol Pete, or so the story goes. While that is said to have happened to him fairly early in his career, the author could find no newspaper references to Ol Pete until 1921. This gives rise to another possible reason for the nickname. By 1921, Alexs penchant for drinking was well known. During Prohibition, bootlegged liquor was sometimes referred to as sneaky Peteand there is plenty of documentation to assure that Alexander partook in his share of bootleg liquor. The author has chosen to use the nickname Pete or Ol Pete in the text that deals with his life and career from 1921 and beyond.

Alexander suffered from alcoholism and epilepsy. Aimee Alexander said some of Alexs problems later in life were the result of epilepsy rather than alcoholism, but there is no way for the author to know for certain. He has relied on accounts of police and hospital reports published in newspapers as well as the published views of managers, teammates and Mrs. Alexander.

I am indebted to Ted Savas for cajoling me many years ago into writing a biography and thereby allowing me to prove to myself that I could do it. His confidence in me six years ago with an entirely different work is, in large part, the reason this book was even undertaken. Several other people assisted in the research, including Gabriel Schechter of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library; MaryAnn Frederick of the Nebraska Historical Society Museum in St. Paul, Nebraska; Jeff Tecklenburg, editor of the Muscatine (Iowa) Journal; Bill Fuhr of the Muscatine Public Library; the staff at Richardson-Sloane Special Collections Center in Davenport, Iowa; baseball history buffs Bill Deane, Cliff Kachline and Steve Steinberg; the staff of the Society for American Baseball Research; and the staff at Retrosheet. A book like this would not be possible without people who may not understand the passion for the work but understand the importance of supporting the person with the passion. People like Jim Collison (who, as an accomplished writer himself, does understand); and Bob Link and Dick Johnson, reporters for the Mason City (Iowa) Globe Gazette, who have been hearing about this for two years, as has Michael Grandon, treasurer of Cerro Gordo County, Iowa.

Special thanks is due to Ed Nevrivy, an 84-year-old retired clothing salesman in St. Paul, Nebraska, one of the few people still alive who knew Grover Cleveland Alexander, who was kind enough to share some recollections with the author.

And finally, none of this would have been possible without my life partner, Sandi Skipper.

John C. Skipper

Mason City, Iowa

April 11, 2006

CHAPTER I

Alone in a Crowd

There is nothing as empty as the echo of yesterdays cheers. New York Mayor Jimmy Walker

On October 6, 1950, 64,505 fans jammed Yankee Stadium for the third game of the World Series between the New York Yankees, on the brink of a dynasty, and The Whiz Kids, the Philadelphia Phillies, who won the pennant by beating the Brooklyn Dodgers on the last day of the season. The Yankees were on their way to winning their second of five straight World Series titles. The Phillies wouldnt win another pennant for 30 years. They paid a steep price for this championship, using their pitching ace, Robin Roberts, in three of the last five games of the season. Roberts came up with the Phillies in 1948 and posted a 79 record. He improved to 1515 in 1949 and then hit his stride in the 1950 championship season, winning 20, losing 11, the first of six consecutive 20-win seasons. But after the grueling last week of the 1950 season, the Phillies wanted to give Roberts an extra day of rest.

Manager Eddie Sawyer tried to pull a rabbit out of the hat. In an effort to rest Roberts and give the rest of the staff a break, too, Sawyer started big, bespectacled Jim Konstanty in the first game of the World Series at Philadelphia. Konstanty had failed to make much of an impression in brief stints with the Reds in 1944 and the Braves in 1946, but after developing a new pitch, a palm ball, he hooked on with the Phillies in 1948, winning one and losing none, and then in 1949, winning 9, losing 5. He enjoyed a tremendous season in 1950, winning 16 and losing only 7 while appearing in 74 games, a league record at the time. But of his 133 major league appearances, all but 13 had been in relief, and he hadnt started a game since 1946 with Boston. Konstantys work in 1950 earned him the leagues most valuable player award, the first ever given to a relief pitcher. But Sawyer took a chance and gave him his first start in five years in the first game of the World Series. He did his job admirably, working eight innings and giving up only one run on four hits, including a run-scoring single by Bobby Brown. Konstantys mound opponent, Vic Raschi, gave up just two hits, and the Yankees won, 10. Game two was almost a repeat of the opener, with Roberts battling Allie Reynolds and the Yankees coming out on top, 21.

Next page