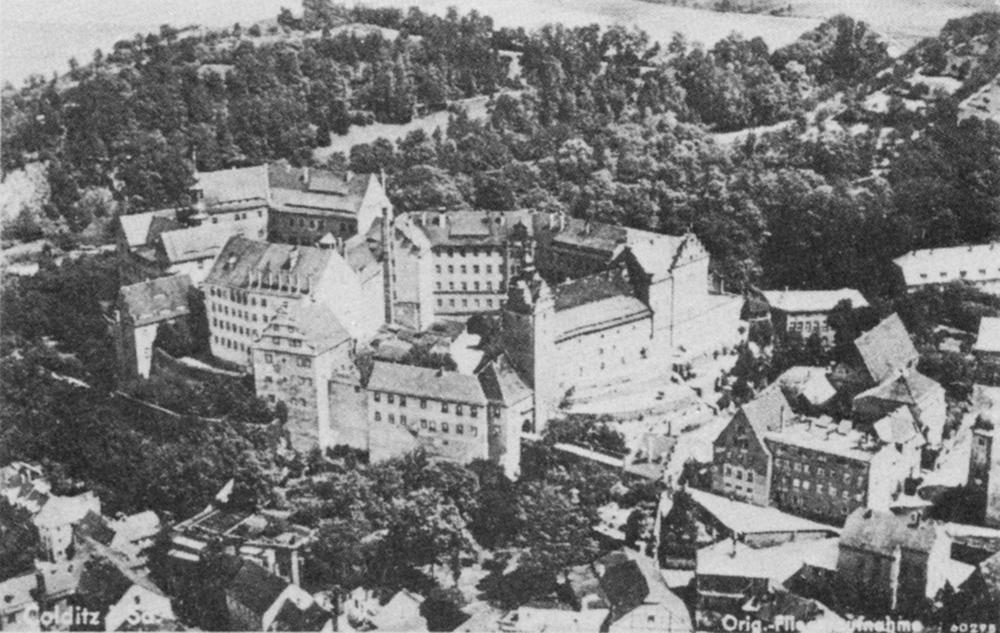

BY REINHOLD EGGERS

It is well known that men are children of their historical period; that the conditions and events of their time shape the main features of mens attitudes, behaviour and general views. No phenomenon of life has a single root; the causes of all things are complex.

In Colditz all the German officers were born in the last fifteen years of the nineteenth century; they had been moulded by the achievements of that time; the foundation of the German Kaiserreich under Prussian leadership; victory over their old sworn enemy France; the industrialisation of the new Reich; the introduction of the first measures for preventing serious distress by disease, age and invalidity through the social laws of the eighties; the revival of Rousseaus old back to nature cry with the Wandervgel movement; the suppression of the Marxist organisation by the Sozialisten-Gesetze, and the prohibition of the social-democratic party up to Bismarcks dismissal under William II. All this was something to be proud of. Our remarkable achievements nourished a belief in the invincibility of the Reich. This exaggeration was personified by The Kaiser with his naval politics and colonial activity. The gleaming weapon, the army, too long trained in the tradition of 18701, fostered an ideal of invincibility.

World War I may have proved us wrong, but it also proved that the old caricatures symbolising the typical dandy German officer with his eyeglass and arrogant bearing were wrong too. Those types were the exception, not the rule. The battlefields showed the true quality of the masses of our officers and soldiers. The politicians had confronted them with an impossible task: to defeat the whole world single-handed, except for an ally of doubtful qualitiesAustria.

The consequence of this shaped a new model of a soldierthe front line fighter, called in the jargon of the trenches Frontschwein. No one subscribed now to the old ideal: the officer or soldier attacking the enemy to a drum roll under the waving regimental colours, with bayonets fixed and swords drawn. In 1914 very few of these main subjects of our training were carried out, still less the formidable cavalry charges of peace-time manoeuvres. The Frontschwein soon laughed at these. Hand-to-hand fighting became a rare event. The killing of the enemy became mechanised, part of an enormous, anonymous machine. There was no use for a bayonet or sword in the destroyed trenches. Hand-grenades, revolvers and machine guns decided the outcome. The stress on human nerves, souls and physical endurance reached limits unknown until then. The Frontschwein had to stand them and he only, indefinitely. Exposed to bombardment from innumerable mortars and guns for hours and even days, seeking shelter in shell holes, in the midst of crying wounded and the silent corpses of the victims who decayed, unburied, for days the Frontschwein had to stand all this, cut off from any communication with the back lines.

I remember an oil picture called ReturnfromtheFront. It showed a lonely road about six kilometres behind the front lines, with some ruins at the side, some bare tree trunks without branches, on a rainy day in December. The road was covered ankle-deep with liquid mud, churned up by the numerous horse-drawn carriages and guns that had ploughed through it during the night. On one side of the road the Frontschweine returned after four days in the front line and four days in the support line into this dreary landscape to some dirty and windy barracks for rest. They marched in single file. You could not distinguish officer from man for their uniforms were covered with clay and mud. Soon they would reach some uncomfortable shelter. It would be hoped that the straw there was dry and that the roof was waterproof, and that the stoves would give some warmth to dry boots and clothing. It was expected that these men after a rest of four days if there was no alarm would return for a second or third period of twelve days to their shell-shattered line; again to be exposed to the merciless Trommelfeuer and to defend this line, imaginary though it was, against attacks. Those who survived could hope to leave this hell, for a longer rest in some region far from this zone of death.

All of them dimly felt their situation to be hopeless, that all this was a kind of madness. Yet nobody saw a way out and so duty alone stood the stress as long as fate demanded it.

This was the ordeal through which almost all men of the Colditz staff and most of the guard company had gone, twenty-five years before. It had left traces in their souls, characters, attitudes; somehow it shaped them into different people from those who had not experienced it. They had become front-line fighters Frontschweine.

Some people had managed to get around these hardships or had only read or heard about them. They made the best of their own situation They were the Etappen-schweine who worked as in peace time, reliably enough, but clinging onto the good things in life as much as possible.

When the reader judges the men of the German staff described in this book, he may bear the above in mind. In short, the characteristics of the Frontschwein are these. He puts his duty first; he sticks to his word; he never leaves his comrades in the lurch; he forms a unit with his crew; he despises the little human vanities like titles, decorations, stilted behaviour, dandylike clothing; he hates self-glorification, boasting, exaggeration of any kind; he esteems and honours the achievements of the simple soldier. According to this scale I weighed the actors at Colditz. I hope I have done justice to everybody; at least I have tried to do so.

I have also tried to present the unusual situation of how I, the old German jailer at Colditz, can co-operate with my former prisoners in preparing this book. I now acknowledge with gratitude to all concerned the help freely given to me when I asked them for their recollections of Colditz.