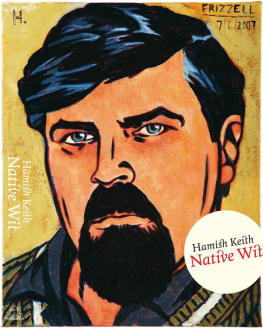

Hamish Keiths most generous gift to us is that he has always insisted on taking New Zealand and New Zealanders seriously. Long before we collectively understood we might dare to have a unique and significant cultural identity, Hamish Keith was both championing its best germinations and railing against the notion that it could be centrally prescribed. He had the audacity to demand merit and to find it where it truly existed rather than where it was decreed. This makes him great company, in life and on these pages. Brilliantly cantankerous, funny, illuminating, naughty, celebratory, he revels in quality where he finds it and gleefully debunks pretenders and committee commissars. He is also a glorious diarist. This bubbling book makes you happy and grateful that such a big, exuberant, wildly intelligent man is ours.

To write the story of your life for others to read is an arrogant business, which is why memorialists devote their prefaces to explaining why. Of all that I have seen Winston Churchills seemed the most honest. History, he said, will treat me well, because I intend to write it. And then there is the most pressing reason of all: I have spent the advance and cannot pay it back. Mine lies somewhere between the two.

More to the point, though, is that ours is a culture in which the writing of letters has practically vanished. Published accounts of lives are all we will have to give us a flavour of times past. Remembering is what memorialists do, and ours is also a culture of forgetting. I am happy to put my hand up for an obligation to memory.

In autobiography memory is the compelling impulse, and memory is not some arid chronology or a dry account of facts. Memory colours, joins up and fills in. Those who have shared some of the events in this book will certainly have a different view of them. Others who have shared events which are not here will wonder why. I have no explanation for either.

I began this story where it should begin, with my birth, and let it go largely where it wanted to go. To be frank, I was sometimes surprised by that and by things I thought would be important which in the end were not. If I did steer this tale at all it was away from things which are properly a part of other peoples lives and, for all that they touched on mine, should remain there.

In the final chapter I make the point that we do not live our lives alone. To all those who have accompanied mine, for better or worse, I am truly grateful and they are clearly too many to name or even remember, but there is some immediate thanks that must be given. To Ngila, of course, to whom this book is dedicated, and to my son Gideon, who skilfully designed it, and to my daughter Julie, who wonderfully enriched my life by coming back into it so unexpectedly. Of course I wonder what my grandchildren David and Sasha, Spike and Ivy, who will one day read their names here, will make of their grandfathers story.

I am grateful beyond words to my friends who found themselves a focus group enrolled to encourage me through the writing of it: Paul Reynolds, Helen Smith, John Campbell, Emma Patterson, Dick Frizzell and Gordon McLauchlan. Dick has also given this book so much colour, as he has my life.

I owe an unpayable debt to those friends who have given me love and sanctuary for so many years and through so many storms: Clare and Freddy Wadsworth, Prue and Marshall Cook, Finola Dwyer, Pasty Reddy and David Gascoigne, Karen Soich and Toni Urlich, and Monique Koorn and Jesse Cardinale. More recently I am grateful for the support of my long-suffering neighbours who have harboured me in my frequent flights from the keyboard, Dona and Gavin White and Roscoe Thorby. Damian Skinner set this whole project off with his careful and patient interviews. I have to thank Nicola Legat for her role of literary midwife and to Stephen Stratford for his gentle editing. I need to record my gratitude here to my oldest friends who have so generously refreshed my memory: Gil Hanly, Michael Volkerling, John Coley, Quentin MacFarlane and Nelson and Janet Kenny. And finally to my sixth-form English master, Tony Hart, who so presciently gave this book its title.

Hamish Keith

Auckland, July 2008

I was not a planned child. I was almost certainly the issue of a celebratory bonk. No need to be a rocket scientist or even an obstetrician to figure it out. The first Labour government was elected on 6 December 1935. I was born on 15 August 1936, just a bit late, which apparently I was. Not a bad beginning, really. A lusty moment of optimism and relief at the end of the long Depression and the promise of something new.

It is tempting to blame my accidental conception for the fact that our family was not particularly close, but the truth is that few Pakeha families of my generation were. Unlike our parents whose families had clung together during world war and Depression, our families readily fell apart. In post-war New Zealand only a few families, with land or money, remained tribal. The school leaving age was 15. Jobs were easy to come by; tertiary education and contraception were not. So for most of us in our late teens it was the highway or the family way and we were out of there. The only difference in my version of that scenario was that I left home aged 18 in a powder-blue tuxedo.

Our family of five stayed in touch but only just. My brother Colin, sister Robin and I all led very different lives; we compacted into our own nuclear families while Mum and Dad morphed unwillingly but unshakeably into one. My last memories of both are a bit of a metaphor. Dad, in a coma, was dying in Christchurch Hospital. I kissed him and said goodbye. Good on you, son, he said, as if I had just stepped into his life for a moment. He was 76. Mum, on the other hand, like most of the women in her family, lived on to a greater age. She died of dementia. On her 92nd birthday, her last, I sent her some flowers. Hamish, she told her nurse. I think we had a dog called Hamish once. I suppose it was a consolation of sorts that she had also forgotten my father.

My fathers family was always a bit of a mystery to me. He, Hamish Farquharson Keith was born in Rangiora in 1906. His four sisters, Malda, Othley, Kathleen and Noeleen, we saw a lot of, his younger brother, Douglas, we saw less there had been some kind of falling out. His mother Beatrice had been born Beatrice Cordy and her mother, also named Beatrice, had been born a Richards. Her father, Henry Richards, a doctor, had arrived in the great cabin of the Sir George Seymour, one of Canterburys first four ships. For some reason our family firmly believed he travelled in steerage another brave little battler but the passenger list has him in more expensive accommodations. The one relic I have of him, which he apparently had on the ship, is a mahogany tantalus, which suggests a taste and lifestyle somewhat out of keeping with steerage.

Another family myth was that his first daughter, my great-aunt, was the first child born in the Canterbury settlement, but since the ships arrived in 1850 and she was born in 1851 that would have made them a more chaste lot than they could possibly have been. My great-grandmother Beatrice Cordy, Henrys second daughter, born in 1860, lived to 92 and she was a terrifying presence in our childhood, something like a Queen Victoria lookalike. My only vivid memory of her was being summoned to be quizzed about clean handkerchiefs and, on producing one, summarily dismissed.

My grandmother was the daughter of James Cordy, whose father John came from Trimley, Suffolk in 1851 on the Travancore. James was 13 and he arrived with two brothers and two sisters. The family were farming at Hororata in Canterbury from 1866. My brother Colins middle name was James (which was also my maternal granddads name, so that took care of both sets of grandparents) and Henry and Cordy are my second and third names so family obligations had a clumsier outcome for me. There is a birth notice for a Cordy daughter at Hororata 1883, which could have been my grandmother, also named Beatrice. The Richards family farmed in Loburn, which is in the same general area. Beatrice and Henry Mortimer Keith were married on 12 November and my grandfathers place of residence was given as Loburn he was farming there according to his wedding certificate.