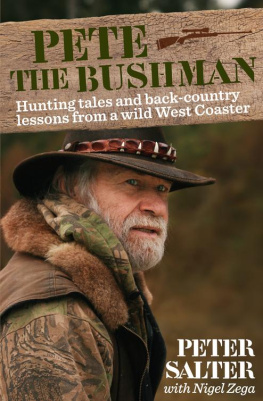

PETE THE BUSHMAN LIVES IN AN ISOLATED TOWN ON THE RUGGED WEST COAST. YOULL FIND IT SOUTH OF HOKITIKA, BETWEEN LAKE IANTHE AND THE WAITAHA RIVER. WHEN YOU GET THERE IT WONT BE BUSTLING. THE POPULATION NUMBERS EXACTLY TWO.

Pete didnt move there to get away from people. He moved there to get away from people telling him how to live his life. Hes been there now for 35 years, trapping, hunting, fishing, eking out a living from the bush.

These are his stories and his lessons, most learned the hard way. They involve weather and women, mountains and helicopters, wild horses and gelignite, bureaucrats, possum pie and the politics of poison.

Strap in and take a ride with a true Kiwi bushman!

To all the friends Ive made over the years. For all the good times and your support through the bad times, thank you.

CONTENTS

Shooting your first stag is a rite of passage. You may not realise it until it happens, but it changes everything. Beforehand, you were just an unproven tramper with a gun. Afterwards, you have joined a realm of people who can put meat on the table. And you have a new understanding of life and death.

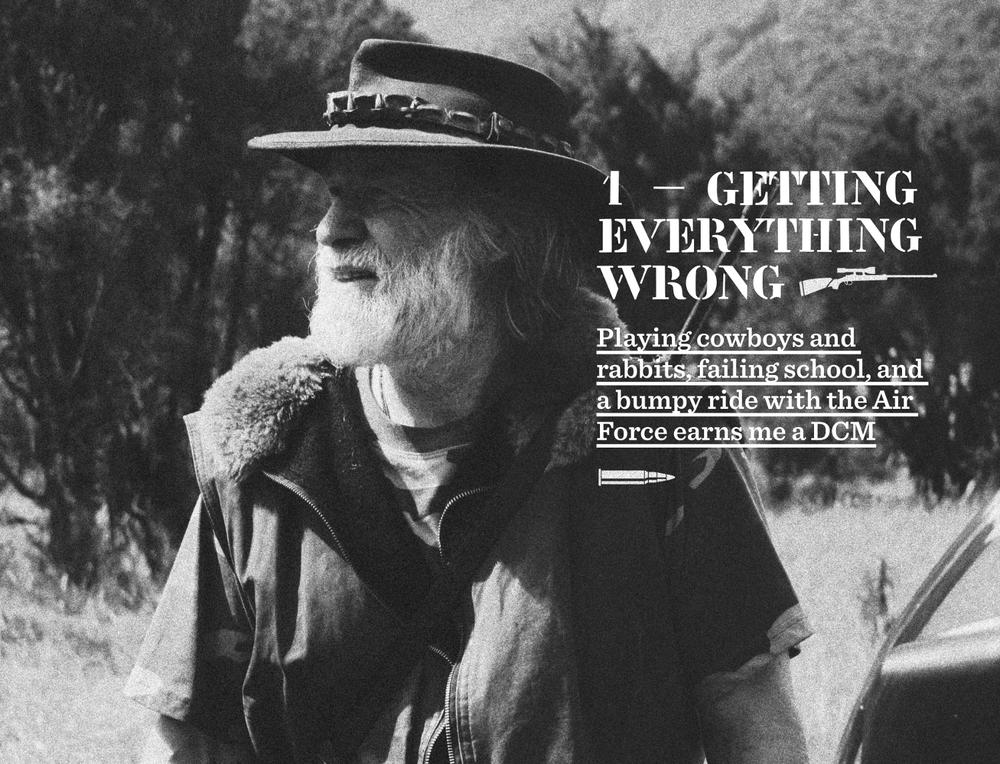

None of this was in my teenage mind when I left Christchurchs Wigram Air Force Base for a weekend hunt. I was riding an old Norton Commando 500 twin, with my friend Cliff on pillion, and we were going to try our luck at Mount Thomas, a conical peak rising some 3350 feet northeast of Oxford.

As a junior airman working in the armoury, you might have thought Id have had the latest military weaponry at my disposal, but the Air Force didnt work that way. Instead, I was carrying an ancient .303, but it was mine and it was paid for, and I fully intended to claim my first stag with it over the weekend. Id made that boast before, of course, but had never made good on it. One of the reasons for this unfortunate state of affairs was that my cheap .303 didnt so much fire bullets as toss them in the general direction of the target. Another reason was the fact that I was bloody useless. I wouldnt go so far as to say I hadnt got a clue about what I was doing, because I had. But that was as far as it went. I had a clue, but no answers.

As an airman cadet I had received instruction on how to shoot at a stationary target of an angry-looking man charging at me with a rifle and bayonet but not on how to shoot at a moving target that would be running away from me at a great rate of knots.

But I was young and keen, and full of the optimism of the ignorant. The day of the hunt dawned fair, which was a relief as Cliff and I had spent the night sleeping under just a fly. Without a tent to pack up, we got an early start. We made our way up through the thick ferns and bracken of the lower slopes and onto a ridge overlooking a wide gut. The ancient rifle felt good in my hands, the air was fresh, and all was right with the world and, Christ almighty, there it was. A bloody stag!

I was looking for one. I was expecting one. I was yearning for one. But I wasnt ready for the jolt it gave me when it turned up. This was a gift. The stag was picking its way delicately up the creek that ran down the middle of the gut, and coming towards us. It didnt even know we were there. We watched in awe as it worked slowly across the scrubby basin and into the bracken on the other side of the gut, getting closer all the time. When it was maybe only 200 yards away, I couldnt stand it any longer. I started banging away at it. Aim, pull the trigger, slide the bolt back and forth, aim, pull the trigger

The stag and I appeared to be on two different planets. I was shooting it and it wasnt being shot. Eventually, it joined me on my planet and started to take notice of the noises on the other side of the gut. It probably recognised what was going on, but realised what a crap shot I was and figured there was no need to panic just yet. But it did start to walk a bit faster, which I felt was an encouraging sign. So I kept at it. Aim, pull the trigger, slide the bolt back and forth, aim, pull the trigger

Shame prevents me from saying how many shots I fired, but I must have connected eventually because the stag finally went down. One second it was standing tall, and the next, it wasnt. It wasnt anything. It wasnt even there. It had been completely swallowed up by the bracken. That was a bit of a jaw-dropper. I was torn between a breathless elation at having finally shot my first stag, and terror at the fear of not being able to find it in the undergrowth. It was all a bit traumatic.

Cliff and I bashed our way over to where we thought it had gone down, and found nothing. We combed the area for an age, with nothing to show but scratches and sweat. How could I shoot a stag and have nothing to show for it? Who would believe me? Would I believe me? And then, there it was, under the ferns, slumped lifeless before me. My stag. My first stag. I had shot my first stag. Until then the reality had not sunk in. It was a thrill like no other, probably based on some primal instinct hard-wired in humans.

In that moment I made a transition. It was a tribal rite of passage that went deep into my soul. I had proved that I could provide food for my family. I had become a man. Of course, I didnt think any of this at the time, but I knew something had changed. On that hillside, almost half a century ago, I felt nothing but an immense and powerful satisfaction.

I had become a hunter. And that was all that mattered.

THAT WAS AN IMPORTANT MILESTONE for me. I didnt realise it then, but hunting gave me a sense of purpose I didnt find elsewhere. It was a simple formula for a life that I could live by. And it didnt involve having to chase around for other people like nearly everyone else I knew. Becoming a bushman meant that no one told me what to do and I was free to do the things I was best at.

Over my years as a full-time hunter, part-time father, sporadic traveller, and general good-time guy, I worked towards realising my dream lifestyle on the wild West Coast of New Zealand. Along the way I learned a few lessons, most of them the hard way, involving weather and women, mountains and helicopters, running businesses, and bumping heads with bureaucrats over possums and the politics of poison.

Its been a crazy ride, but I wouldnt have missed it for the world.

Standing over my first stag on Mount Thomas, I had become a hunter. It felt good. I took the head to honour the moment. It was a puny little thing, but Ive still got it somewhere. But what I did next haunts me to this day. I committed what I now consider a cardinal sin. I left the rest of the stag where it lay. I should have kicked myself silly for not taking the meat, but I was young and stupid and flushed with the thrill of success.

I wasnt respecting the life I had just taken. I was wasting it. It was the first time and the last time I ever did anything like that. Since then, Ive lost deer in unfortunate circumstances but Ive never again shot for the sake of it. I still had a lot of growing up to do on that hillside, but I quickly learned to appreciate the gulf between life and death.

Next page