H. W. Tilman

Introduction

by Jim Perrin

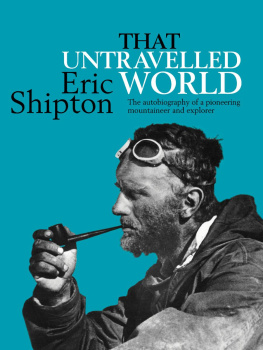

More than in any other genre the effect of travel writing depends on personal response to the author. Half an hour of Doughtys quirky pomposity is enough for anyone not intent on sleep; D. H. Lawrence might just entice you into the intoxication of a sunny afternoon; there are very few whom you would take willingly to the uttermost parts of the Earth, but H. W. Tilman belongs in this latter category. The re-publication of the seven titles collected together in this volume has long been overdue, for Tilman is unsurpassed as a mountaineering author, and can hold his own with any travel writer in the language.

These seven books are a form of restrained autobiography covering the years 1919-1952. Snow on the Equator can be read as an idiosyncratic account of the authors attempt to find his personality, or more simply as a fascinating thirties African travelogue. The Ascent of Nanda Devi and Everest 1938 are as close to conventional accounts of expeditions to big mountains as Tilman could countenance, and have long been regarded as classics of their kind. When Men and Mountains Meet covers a pre-war trip to the little-known Assam Himalaya and goes on to describe Tilmans Second World War experiences. The three books dealing with his post-war travels Two Mountains and a River, China to Chitral, Nepal Himalaya are those on which his fame will probably rest and are descriptions of an extraordinary series of individual peregrinations through every major range of the Himalaya and Central Asia.

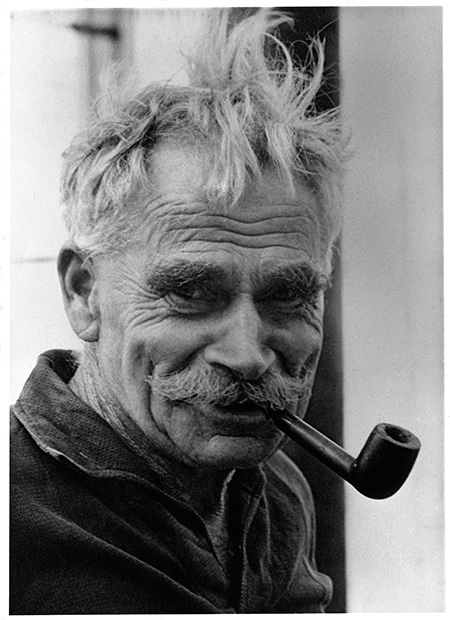

The personality of the author is central to the matter of travel writing, yet that of Tilman, despite a painstaking biography, remains enigmatic and elusive. The boat on which he was sailing for the Antarctic disappeared in the South Atlantic six years ago in a season of storms. The tragedy became apparent when the boat failed to arrive at any likely port of call. For Tilman it was a curiously apt and romantic ending, setting the seal on the legend of his life.

Far too many, on the evidence of the numerous apocryphal tales which have collected about him, have pre-judged Tilman as the slightly blimpish and austere monomaniac conqueror of peak, ocean or Asian col an unconsciously humorous misogynist cast in a sterling British Imperial mould.

Such a judgment is manifestly incorrect. There is little point in recapitulating on the events of a life already well recorded in the Anderson biography. Instead this preface may best serve as the character, in the eighteenth-century sense of the word, of a slightly anachronistic, yet profoundly civilised and intelligent man for whom such a gesture is entirely appropriate.

In a way, the manner and timing of his death, so tragic for his young fellow-sailors, was for him a blessing. In the last conversation I had with him before he sailed for the Antarctic, he confessed that he felt himself to be getting feeble now, and that he would not mind if he did not come back from this trip this said quite matter-of-factly, and with not a trace of self-pity. Pam Davis, his niece and probably the person closest to him in his last years, put it thus: The way he went it just couldnt have been better. It was just absolutely perfect. The idea of him being ill or nursed was unthinkable. The pity of it was that those boys went too, but at least he wasnt in charge it was their expedition, and their boat, on which hed been invited along.

Tilman was a lifelong bachelor and reputedly a misogynist, which gave rise to the usual run of unfounded gossip and wrong-headed speculation, as well as the reputation of humourlessness. Some months before he sailed on his last voyage, I asked him why he had never married. He replied, grinning hugely to himself at my presumption, Ive had my peccadilloes, but the trouble with women is, they get in the damned way. Theres nothing the least sexist about his reply an adventurous woman could give the same response about men. A marital partner, family commitments and the like would have acted as constraints upon the pattern of life he came to discern in the twenties, and seeing this, he wisely and unselfishly for there is an element of moral choice here as well as working out a mode of individual integrity disciplined himself and forwent the pleasures along with the responsibilities of marriage. He was certainly aided in this decision by the close relationship he enjoyed throughout his life with his sister Adeline who had been left, after the break-up of her marriage, with two small daughters who grew particularly close to their uncle and possibly regarded him in the light of a rather distant, but fascinating and romantic father-figure. His needs for female companionship and support were amply fulfilled through Adeline, with whom he went dancing, for whose children he brought back presents African stools, elephant tails from his trips, and with whom he eventually made his home in Wales. Tilman was, in his own way, a family-orientated man and one who blossomed amongst the company of relations and close friends.

His attitude to women was rather that of an old-fashioned courtesy. Although he could and did appreciate simple, honest ribaldry on his Asian trips, impropriety towards his family was a different matter. Pam Davis has a recollection of accompanying him to the twentieth anniversary celebrations of the liberation of Belluno in the Dolomites. After introducing Pam, then a strikingly handsome woman in her early forties, to his old partisan friends as his niece they were shown, amidst a good deal of nudging and winking, to a double hotel bedroom. Pam recounts how she strove to suppress laughter as he furiously rounded on his hosts to insist, thunderously and with piercing blue eyes, She is my niece! I have to add that such an unamused reaction would have been occasioned only by his strict sense of family propriety.

Which brings us back to the point of his reputed humourlessness. Such an accusation is crass beyond belief. Tilman was the funniest man I ever met and for proof of that assertion you need do no more than dip into this book. They are laced with self-mockery, continual ironic reflection, moments of high farce, and a due sense of the ridiculousness inherent in so many of our actions.

One of his chief joys in conversation was to send up the accepted image of himself mercilessly. I remember asking how many of the stories which grew up about him were apocryphal. By far the greater number, he replied, but there is one which is substantially true. It was on an expedition in the thirties. We embarked at Tilbury, and I am said to have stayed on deck until we rounded the North Foreland, whereupon I was heard to mutter the words, Hm, sea! After this I went below decks and was not seen again until we hove in sight of Bombay. I then came on deck once more and was duly heard to utter the words, Hm, land! It is asserted that these were the only words I uttered on the entire voyage, which is more or less the truth of the matter, and the reason, quite simply, is that I could not stand the other chaps on that trip.