Also by Deborah Devonshire

The House: A Portrait of Chatsworth (1982)

The Estate: A View from Chatsworth (1990)

Farm Animals (1991)

Treasures of Chatsworth: A Private View (1991)

The Garden at Chatsworth (1999)

Counting My Chickens and Other Home Thoughts (2001)

Chatsworth: The House (2002)

The Duchess of Devonshires Chatsworth Cookery Book (2003)

Round About Chatsworth (2005)

Memories of Andrew Devonshire (2007)

Home to Roost and Other Peckings (2009)

Letters from Deborah Devonshire are included in:

The Mitfords: Letters between Six Sisters (2007)

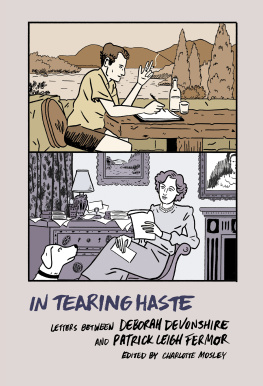

In Tearing Haste: Letters between Deborah Devonshire and

Patrick Leigh Fermor (2008)

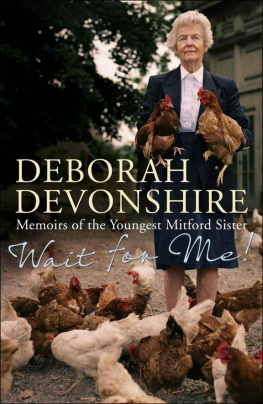

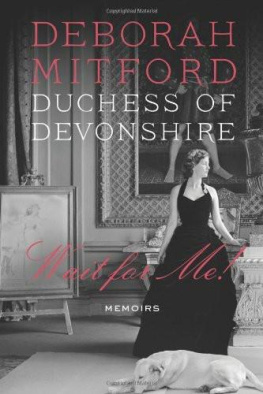

Wait For Me!

Memoirs of the Youngest Mitford Sister

DEBORAH DEVONSHIRE

www.johnmurray.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by John Murray (Publishers)

An Hachette UK Company

Deborah Devonshire 2010

The right of Deborah Devonshire to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978-1-84854-457-4

Book ISBN 978-1-84854-190-0

John Murray (Publishers)

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.johnmurray.co.uk

To

Charlotte Mosley, my editor

Helen Marchant, my secretary

and my old friends Richard Garnett and Tristram Holland

who gave me the confidence to keep trying

Contents

Illustrations

Section One

Section Two

Section Three

Section Four

Note on Family Names

My family used nicknames usually as terms of affection, but sometimes the opposite. To spare the reader the irritation of ever-changing names, I have generally used those we were given at our christening. This seems strange to me because I never did so in real life but I hope it will make things plainer for my readers.

For the record, my parents were Muv and Farve obvious enough. Muv had a string of other names including Aunt Sydney, because that is what our cousins called her, and Lady Redesdale, which strangers called her. Farve was Morgan to Jessica and Unity, for no particular reason. Nanny was Blor or mHinket; she did not like either but did not try to stop us. Because of her black hair, Muv and Farve called Nancy Koko after the Lord High Executioner in The Mikado. Pam and Diana called her Naunce and to me she was the Ancient Dame of France, the French Lady Writer or just Lady. Pam was Woman to us all, with variations thereof. Tom was Tuddemy to Unity and Jessica (Tom in Boudledidge, their private language) and this was taken up by the rest of us. Diana was Dayna to Muv and Farve, Deerling to Nancy, and Honks to me. I still have to think who I am talking about when she is Diana. Unity was Bobo, but Birdie or Bird to me. Jessica called her Boud (Bobo in Boudledidge). Jessica was Little D to Muv, Stea-ake to Pam and Hen or Henderson to me, but she was Decca universally and remains so in this book. I have always been Debo to most, but Hen to Jessica, Swiny to Unity, and Nine, Miss and lots more to Nancy. I was Stubby to Muv and Farve, after my short fat legs which could not keep up (hence the title of this book). Our names changed with the wind but the ones none of us ever spoke were Nancy, Pamela, Thomas, Diana, Unity, Jessica and Deborah.

I always had nicknames for my husband, Andrew, which changed over time. For many years it was Claud, because when he was Lord Hartington he got letters addressed to Claud Hartington. My mother-in-law was Moucher to one and all (after the character in David Copperfield) I never heard anyone call her Mary. My elder daughter, Emma, is Marlborough or Marl because of her Girl Guide uniform, which was smothered in badges like the much-decorated Mary, Duchess of Marlborough. My younger daughter, Sophy, is Moffa goodness knows why. The only one of my childrens nicknames I have used throughout the book is Stoker, which for some reason he has never managed to throw off. He now signs himself Stoker Devonshire. I call him Sto.

1

We Are Seven

B

LANK. THERE IS no entry in my mothers engagement book for 31 March 1920, the day I was born. The next few days are also blank. The first entry in April, in large letters, is KITCHEN CHIMNEY SWEPT. My parents dearest wish was for a big family of boys; a sixth girl was not worth recording. Nancy, Pam, Tom, Diana, Bobo, Decca,

me, intoned in a peculiar voice, was my answer to anyone who asked where I came in the family.

The sisters were at home and Tom was at boarding school for this deeply disappointing event, more like a funeral than a birth. Years later Mabel, our parlourmaid, told me, I knew what it was by your fathers face. When the telegram arrived Nancy announced to the others, We Are Seven, and wrote to Muv at our London house, 49 Victoria Road, Kensington, where she was lying-in, How disgusting of the poor darling to go and be a girl. Life went on as though nothing had happened and all agreed that no one, except Nanny, looked at me till I was three months old and then were not especially pleased by what they saw.

Grandfather Redesdales huge house and estate in Gloucestershire, Batsford Park near Moreton-in-Marsh, was inherited by my father in 1916. It was too expensive to keep up and was sold in 1919. My father looked for somewhere more modest near Swinbrook, a small village where he owned land, fifteen miles from Batsford. There was no house there suitable for a family of six children and a seventh on the way, so he bought Asthall Manor in the neighbouring village. I was born soon after the move and my earliest recollections are of the ancient house and its immediate surroundings. Asthall is a typical Cotswold manor, hard by the church, with a garden that descends to the River Windrush. It was loved by my sisters and Tom, and the seven years spent there were probably the happiest for parents and children, the proceeds of the sale of Batsford giving the family a feeling of security that was never repeated.

There was, and is, something profoundly satisfying in the scale of Asthall village. It was a perfect entity where every element was in proportion to the rest: the manor, the vicarage, the school and pub; the farmhouses with their conveniently placed cowsheds and barns; the cottages, whose occupants supplied the labour for the centuries-old jobs that still existed when we were children; and the pigsties, chicken runs and gardens that belonged to the cottages. Before cars and commuters, you lived close to where you worked and the shops came to you in horse-drawn vans. This was the calm background of a self-contained agricultural parish, regulated by the seasons, in an exceptionally beautiful part of England.

My father planted woods to hold game, as well as a short beech avenue leading up to the house, and his dark purple lilacs outside the garden wall are still growing there after nearly a hundred years. The house itself needed much restoration. My mothers flair for decoration and her talent for home-making ensured that the French furniture and pictures from Batsford were shown at their best. My father installed water-powered electric light just the sort of contraption he adored; drawing heavily on his umpteenth cigarette, he would lean over the engineer, itching to do the job better himself. He made sure he had a child-proof door to his study by putting the handle high up out of reach. Sometimes we heard the voice of Galli-Curci singing Farves favourite aria, coming loudly from the outsize horn of his gramophone a twin of the one in advertisements for His Masters Voice. In another mood he might put on The Diver (He is now on the surface, hes gasping for breath, so pale that he wants but the stillness of death), sung by Signor Foli in a terrifying and unnaturally low bass voice.

Next page