B Y J ESSICA M ITFORD

The American Way of Death Revisited

The American Way of Birth

Grace Had an English Heart

Faces of Philip: A Memoir of Philip Toynbee

Poison Penmanship: The Gentle Art of Muckraking

A Fine Old Conflict

Kind and Usual Punishment: The Prison Business

The Trial of Dr. Spock

The American Way of Death

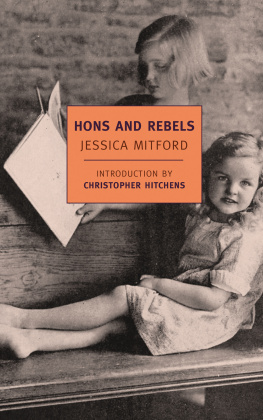

Hons and Rebels (previously published as Daughters and Rebels)

B Y P ETER Y. S USSMAN

Committing Journalism

T O D ECCA

For her inspiration

A ND TO P AT

For her love and tolerance

Contents

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

Introduction

Jessica Mitford, daughter of the second Lord and Lady Redesdale, escaped from the milk-bland life of the Cotswolds in prewar England and spent the rest of her illustrious life and careerand her extensive correspondencein a kind of continuing conversation, or argument, with her privileged upbringing, her unruly family, and the tempestuous political passions of the era in which she was raised.

She once recalled telling an interviewer that I Led Three Lives would have made a good title for her first memoir, only unfortunately it had been used by the FBI and of course I wouldnt have anything to do with them as I despise them. As usual, her arithmetic was wrong, but uncharacteristically she erred on the conservative side. The myriad lives of Jessica Mitford, known to friendsand even at times to the FBIas Decca Treuhaft, included the three that she probably had in mind in that 1960 interview: rebellious fifth daughter of reactionary and notoriously eccentric English aristocrats; full-time American Communist Party organizer and civil rights activist through much of the 1940s and 50s; and, at the time of her interview, a middle-aged author plugging her first book.

Over the ensuing decades until her death in 1996, Decca was best known in the United States as a distinguished and wickedly irreverent muckraking journalist, celebrity wit, and authormost notably of The American Way of Death, a runaway best-seller in 1963 that forever changed the countrys funeral practices. In England, she may be remembered best as the Honorable Jessica Mitford, one of the Mad Mitfords or the Mitford Girls, the six sisters who entranced and infuriated the British public through much of the twentieth century.

Along the way, she moved easily among the worlds Most Important Peoplearistocrats and meritocrats, politicians, radical intellectuals, artists, writersas well as the misfits and outcasts whose grievances she championed and whose stories she brought to public attention. Very few people could straddle so effortlessly the many worlds she inhabited, but her ability to do so was a source of many of her most enduring achievements, as a writer, as a social critic and reformer, and as a mother, friend, and mentor.

From the time the teenager first made the front pages as Peers Daughter escaping her largely fascist family and eloping to the Spanish Civil War, Decca was rarely out of the headlines for long. A few years later, after she and her first husband, Esmond Romilly, the brilliant and engaging naughty boy nephew of Winston Churchill, emigrated to the United States, their escapades as Baby Bluebloods in Hobohemia were serialized prominently in the Washington Postand syndicated to other papersand her photo was on the Posts front page when their daughter Constancia was born. Journalists sought her out every time one of her fascist sisters made headlines of her own. Still later, the press was reporting on Deccas Communist Party activities and confrontations with congressional Red-hunters and her disinheritance by Baron Redesdale. For decades thereafter, with each new book and article, she gained a new measure of renown.

Deccas very public life and her inimitable personality are refracted in her extensive, lifelong private correspondence. Her letters amount to a characteristically uninhibited and revealing form of autobiography, but they are also a kind of social history and commentary. The correspondent list of this self-described renegade aristo is an idiosyncratic Whos Who of a century in breathtaking transition, and her always original voice helps to illuminate that century and its quirks.

As newspaper feature writers never tired of reminding their readers, Time magazine conferred on Decca the hybrid Anglo-American title Queen of the Muckrakers. I rather loved it, she told one reporter. If they were going to mention me at all, Im glad it was as a queen. But a more appropriate title might be Mother of New Journalism. Deccas work is a reminder that some of the best journalism comes about in the most unconventional ways. She was a brilliant agent provocateur who, through withering humor, offbeat observations, unflinching directness, and sheer force of personality, flayed social injustice and often provoked her adopted country to glimpse itself with unaccustomed clarity. Like many of the New Journalists, her life and her art were at times inseparable, a kind of social and political theater; her writings and her conduct combined to form a critique of the society in which she lived. The two strains merge in her correspondence, along with the biographical and social roots of that distinctive achievement, going back to childhood.

The Mitford daughters and their brother, Tominsulated from even their peers by the conventions of their classgrew up in what Decca called in her first memoir a timeproofed corner of the world, foster children, if not exactly of silence, at least of slow time. Their parents, she once said, saw Englands socioeconomic classes as traveling along parallel tracks that could never meet or intersect in any way.

By all accounts, the uninhibited Mitford children lived a self-sufficient life of tradition and frivolity punctuated by their charming but sclerotic fathers blustering outbursts. They filled their circumscribed world with a culture of their own invention; one commentator called them a savage little tribe. They played childhood games that sometimes seemed cruel to outsiders; they communicated in secret, made-up languages, and they patented the Mitford tease, an unrelenting form of ridicule that Decca later turned outward on the world. She once quoted family friend Robert Kee as saying, It has always seemed to me that your family regards the rest of the world, and everything that happens in it, as a huge joke put on for their benefit. Foremost promoter of this form of huge jokeat a time when it was still primarily a form of sisterly torture and then, later, in her popular novelswas the eldest daughter, Nancy.

Lord and Lady Redesdale did not believe in school for their daughters. (Throughout Deccas distinguished career as a writer, her rsum included the line Education: Nil. Autodidact.) Deccas resentment, she wrote, was absolutely burned into my soul, so that decades later on another continent, the subject came up and I found myself literally fighting back tears of rage. She told her sister Nancy once that when they were children Decca couldnt confide to Nancy her secret childhood ambition to be a scientist because whenever one told you ones deepest ambitions it was only to be TEASED UNMERCIFULLY and laughed off face of earth.