NANCY MITFORD (19041973) was born into the British aristocracy and, by her own account, brought up without an education, except in riding and French. She managed a London bookshop during the Second World War, then moved to Paris, where she began to write her celebrated and successful novels, among them The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate, about the foibles of the English upper class. Nancy Mitford was also the author of four biographies: Madame de Pompadour (1954; available as an NYRB Classic), Voltaire in Love (1957), The Sun King (1966), and Frederick the Great (1970). In 1967 Mitford moved from Paris to Versailles, where she lived until her death from Hodgkins disease.

PHILIP MANSEL is the author of six books dealing with French history, including a life of Louis XVIII (1981), The Court of France, 17891830 (1989) and Paris Between Empires (2001). He is currently at work on a life of Louis XIV.

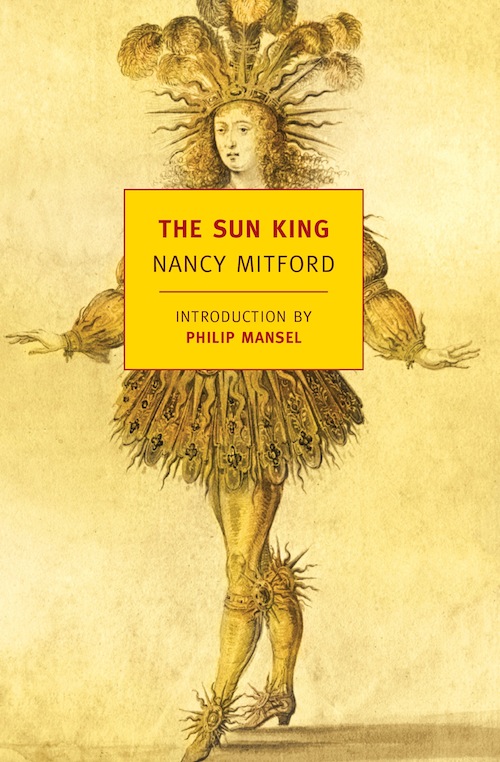

THE SUN KING

Louis XIV at Versailles

NANCY MITFORD

Introduction by

PHILIP MANSEL

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

On October 16, 1928, Nancy Mitford wrote to her brother Tom: Have you been to Versailles yet? It is my spiritual home and at this time of year is the most divinely melancholy place in the world. The passion revealed in these words found its finest expression in the publication in 1966thirty-eight years laterof The Sun King. An ideal marriage of author, subject, and format, on publication it sold 250,000 copies, was translated into seven languages (including French) and has never been out of print in England.

Versailles was more than a royal palace. It was also a seat of government; a national job center and social security office, distributing hundreds of appointments and pensions; an information center receiving couriers from throughout Europe; a year-round reception, ball, concert, and fashion parade; a marriage market and finishing school; and a hub of creativity inspiring music, plays, operas, letters, diaries, and memoirs (by, in the reign of Louis XIV, among many others Lully, Rameau, Racine, Molire, Madame de Svign, and the Duc de Saint-Simon). In addition to staterooms and hundreds of apartments, it also housed the royal familys art collections and scientific laboratories; a chapel, where the king attended religious services most days of the year; kitchens serving hundreds of meals; and vendors stalls. Its outbuildings contained the ministries of war and foreign affairs, guards barracks, stables, riding schools, and hunt kennels. The palace was surrounded on the east by parade grounds for the kings household troops and court officials houses, on the west by a sweep of gardens and parks. Versailles also functioned, as preachers in the chapel often lamented, as a gambling den and a brothel.

To this multidimensional universe, more varied and stimulating than the Internet today, Mitford brought her novelists interest in human nature and physical detail; her gift for narrative and entertainment; and the passion for that celestial land, France, which had been one reason for her move from London to Paris in 1946, and which drives her books Madame de Pompadour (1954) and Voltaire in Love (1957) and her novels TheBlessing (1951) and Dont Tell Alfred (1960). The other reason was her love for the French politician, and confidant of de Gaulle, Gaston Palewski.

Reproducing many phrases culled from contemporary letters and memoirs, Mitford begins with the kings love affair with Louise de La Vallire, which helped spur him to visit Versailles in the 1660s. She then describes the subsequent mistresses going up and down the Queens staircase. Madame de Maintenon, the Governess, whose combination of piety, world-liness, poor judgment, disloyalty towards friends, and mismanagement of the girls school that she founded at Saint-Cyr, is analyzed with distaste. One chapter, The Faculty, describes the incompetent doctors under whom, then as now, while the strong survive; the weak, after much suffering and expense both of money and spirit, die. She does not neglect the royal artists Le Vau and Le Brun and the gardener Le Ntre, nor the kings rival ministers Colbert and Louvois. Separate chapters are devoted to the younger generation of the kings bastards, cousins, and nephew. Three in eleven months describes the deaths of the kings son the Dauphin and his grandson and granddaughter-in-law, the Duc and Duchesse de Bourgogne in 171112. Throughout the book Mitford shows that the court of Versailles consisted not just of the king and his family and friends but of an entire society of ministers, diplomats, officers, preachers, gardeners, and other professions: a microcosm of France. Below the appearances of deference, they could manipulate as well as serve the king.

Physical details are telling. While the king, the viceroy of the Almighty, faced the altar as he worshipped God in the chapel, the courtiers stared at the king. The king held a stick across a door in Saint-Cyr, only lowered for those who had truly been invited to a performance of Racines play Esther in January 1689. The princes of the House of Cond became so physically small and mentally strange that they resembled little black beetles. The melancholy smiles of Mary of Modena were the only satisfactions Louis XIV derived from his decision to recognize her son the Old Pretender as king of England. The opening sentence is famous: Louis XIV fell in love with Versailles and Louise de La Vallire at the same time; Versailles was the love of his life.

Mitford describes Versailles, correctly, as a shop window, a permanent exhibition of French goods, which made an enormous contribution to French supremacy in the arts. The hereditary system for offices, from ministers to gardeners, was its foundation: he built the greatest palace on earth but it always remained the home of a young man, grand without being pompous, full of light and air and cheerfulnessa country house. She describes the Galerie des Glaces as the palaces main street or market place. Not all readers, however, will agree that this gallery, which contains more images of the monarch it glorifies than any other, is one of the beauties of the western world.

If she idealizes the palace, it is not true that she idealizes Louis XIV. She describes him as a man of iron, unbowed by deaths or defeats. He was secretive, ruthless, indifferent to the sufferings of peasants and galley slaves, capable of inspiring terror and making blunders such as the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the imposition of the papal bull Unigenitus on the French bishops. Hardly had he assembled his most interesting and important subjects under his roof than he retired into almost private life with an ageing spouse [Madame de Maintenon] and her circle of excellent nonentitiesalthough Louis XIVs private life still resembled other peoples public life.

The text was checked by two historians, John Lough and Ian Dunlop, but there are exaggerations. Lord Portland, sent as ambassador to Louis XIV by William III in 1698, is unlikely, unless he had a very silent marriage, not to have spoken a word of English. He preferred French but could understand, and write, English, and his wife, a member of the Villiers family, was English. The place in the order of succession to the throne to which Louis XIV elevated his bastards is exaggerated (they came after, not before, the princes of the blood); and he is absolved, implausibly, from knowledge of the ravaging of the Palatinate. Nevertheless