Contents

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by Flamingo 1997

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1996

Copyright J. G. Ballard 1996

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Author photograph by Jerry Bauer

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007292790

Ebook Edition MARCH 2014 ISBN: 9780007484201

Version: 2017-03-24

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W 1A8, Canada

www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

www.harpercollins.com

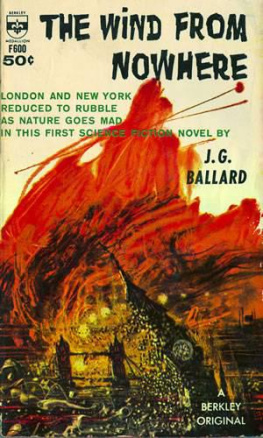

J. G. BALLARD was born in 1930 in Shanghai, where his father was a businessman. After internment in a civilian prison camp, he and his family returned to England in 1946. He published his first novel, The Drowned World, in 1961. His 1984 bestseller Empire of the Sun won the Guardian Fiction Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. His memoirMiracles of Life was published in 2008. J. G. Ballard died in 2009.

THE DROWNED WORLD

THE VOICES OF TIME

THE TERMINAL BEACH

THE DROUGHT

THE CRYSTAL WORLD

THE DAY OF FOREVER

THE VENUS HUNTERS

THE DISASTER AREA

THE ATROCITY EXHIBITION

VERMILION SANDS

CRASH

CONCRETE ISLAND

HIGH RISE

LOW FLYING AIRCRAFT

THE UNLIMITED DREAM COMPANY

HELLO AMERICA

MYTHS OF THE NEAR FUTURE

EMPIRE OF THE SUN

RUNNING WILD

THE DAY OF CREATION

WAR FEVER

THE KINDNESS OF WOMEN

RUSHING TO PARADISE

A USERS GUIDE TO THE MILLENNIUM (NF)

COCAINE NIGHTS

My thanks go to David Pringle for his invaluable help in collating this selection of my essays and reviews of the past thirty years, and for his many editorial suggestions.

The Sweet Smell of Excess

Writers in Hollywood 1915-1951

Ian Hamilton

In his prime the Hollywood screenwriter was one of the tragic figures of our age, evoking the special anguish that arises from feeling sorry for oneself while making large amounts of money. His plight is summed up in Sunset Boulevard, where Joe Gillis ends his unhappy career lying face down in the swimming pool he always wanted, rather than admit his failure and go back to the humble newspaper office in Dayton, Ohio.

Nowadays, of course, his successors lie face up in their Hollywood pools, with not a tragic shudder among them, and the huge fees they receive, often for scripts that are never filmed, could buy most provincial newspapers outright. But the problem of the screenwriters role still remains, especially when the director is once again taking almost all the credit for any success. What part is played by the film script, how much does the screenwriter contribute to a film, and does he merit the status which literary people generally assign him? The difficulty of answering these questions lies at the heart of the unsatisfactory Hollywood careers of Chandler, Fitzgerald, Faulkner and Nathanael West, which fixed for ever the popular myth of the literary artist exploited and degraded by a philistine industry.

With some reservations, Ian Hamilton seems to accept this point of view, tracing the history of the screenwriter from the silent era, when regiments of ex-newspapermen were hired to rough out storylines and supply static captions, to the birth of sound and the recruitment in the 1930s of a far classier and more self-important literary set the serious novelists, Broadway playwrights and Algonquin wits, who were patronizing about the crudities of popular film but had noticed that the green slopes of Beverly Hills were covered, not with leaves, but thousand-dollar bills. All of them, to varying degrees, made the mistake of assuming that the primary creative contribution to a film would come from themselves.

Much of Hamiltons book is drawn from the standard defensive biographies of Chandler, Fitzgerald and co., and a stale air hangs over these anecdotes. He never asks why these pre-eminendy literary writers so failed to get to grips with Hollywood. Like most outsiders he underestimates the importance of the producer, in many ways the greatest creative force in film. He knows nothing about screenwriting or, for that matter, the writing of fiction, and misconceives the function of the scriptwriter, which lies closer to the original role of story-outliner and caption-supplier.

As far as the novel is concerned, the importance of the writer is still paramount, though all of us have learned to keep a close eye on the rear-view mirror. In the theatre the playwright is at least the equal partner of the performers, but in film the writer is shouldered aside by director, actor, producer and editor, who together transform the printed word into something far more glamorous and evocative.

Years ago I was offered the chance to do the novelization of a film then being made by a leading British director. The script outlined a hackneyed story about a malevolent stowaway, with dialogue that rarely rose above Chow-time. Wheres Dallas? Topside. Uh-huh. What amazed me was not that someone had decided to film this script, but that he had been able to form any idea of the finished movie from these empty lines. Yet the film was Alien, one of the most original horror-movies ever made, and the throwaway dialogue perfectly set off the terrifying vacuum that expanded around the characters.

By some unexplained alchemy, a film can effortlessly transform sentimental clichs into something emotionally compelling, as in Sunset Boulevards last lines: Life, which can be strangely merciful, had taken pity on Norma Desmond. The dream she had clung to so desperately had enfolded her No serious novelist would dare to end a book with these lines, and no middlebrow writer would have the talent to invent them. But Billy Wilder is the exception. He may have quarrelled with Raymond Chandler (over