Annotation

There's something wrong with Estrella Del Mar, the lazy, sun-drenched retirement haven on Spain's Costa Del Sol. Lately this sleepy hamlet, home to hordes of well-heeled, well-fattened British and French expatriates, has come alive with activity and culture; the previously passive, isolated residents have begun staging boat races, tennis competitions, revivals of Harold Pinter plays, and lavish parties. At night the once vacant streets are now teeming with activity, bars and cafes packed with revelers, the sidewalks crowded with people en route from one event to the next.

Outward appearances suggest the wholesale adoption of a new ethos of high-spirited, well-controlled collective exuberance. But there's the matter of the fire: The house and household of an aged, wealthy industrialist has gone up in flames, claiming five lives, while virtually the entire town stood and watched. There's the matter of the petty crime, the burglaries, muggings, and auto thefts which have begun to nibble away at the edges of Estrella Del Mar's security despite the guardhouses and surveillance cameras. There's the matter of the new, flourishing trade in drugs and pornography. And there's the matter of Frank Prentice, who sits in Marbella jail awaiting trial for arson and five counts of murder, and who, despite being clearly innocent, has happily confessed.

It is up to Charles Prentice, Frank's brother, to peel away the onionlike layers of denial and deceit which hide the rather ugly truth about this seaside idyll, its residents, and the horrific crime which brought him here. But as is usually the case in a J.G. Ballard book, the truth comes with a price tag attached, and likely without any easing of discomfort for his principal characters.

Cocaine Nights marks a partial return on Ballard's part to the provocative, highly-successful mid-career methodology employed in novels such as Crash and High Rise: after establishing himself as a science fiction guru in the 1960s, Ballard stylistically shifted gears towards an unnerving, futuristic variant on social realism in the 1970s. Both Crash and High Rise were what-if novels, posing questions as to what the likely results would be if our collective fascination with such things as speed, violence, status, power, and sex were carried just a little bit further: How insane, how brutal could our world become if we really cut loose?

Cocaine Nights asks a question better suited to the '90s, the age of gated communities and infrared home security systems: Does absolute security guarantee isolation and cultural death? Conversely, is a measure of crime an essential ingredient in a vibrant, living, properly functioning social system? Is it true, as a character asserts, that "Crime and creativity go together, always have done," and that "total security is a disease of deprivation"? Suffice to say that the answers presented in Nights will be anathema to moral absolutists; the world of Ballard's fiction, like life in the hyperkinetic, relativistic 1990s, abounds with uncomfortable grey areas.

On the surface, Cocaine Nights is a whodunit and a race against time, but as it proceeds - and as preconceived conceptions of good and evil begin to dissolve - it evolves into a thoughtful, faintly frightening look at under-examined aspects of 1990s western society. As is his wont, Ballard confronts his readers with some faintly outlandish hypotheses unlikely to be embraced by many, but which nonetheless serve to provoke both thought and a bit of paranoia; it's a method that Ballard has developed and refined on his own, and as usual, it propels his novel along marvellously.

Cocaine Nights doesn't have either the broad sweep or brute impact of the landmark Crash, but it retains enough social relevance and low-key creepiness to more than satisfy Ballardphiles. As is often the case in Ballard's alternate reality, it's a given that his most appealing, human characters turn out to be the most twisted, and that even the most normal of events turn out to be governed by a perverse, malformed logic; that this logic turns out to be grounded in sound sociological and psychological principles is its most horrific feature.

David B. Livingstone

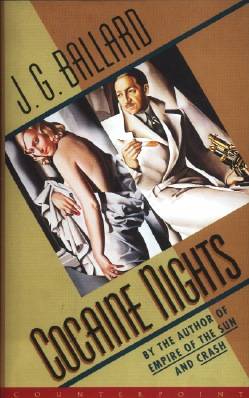

J.G. Ballard

Cocaine Nights

1 Frontiers and Fatalities

Crossing frontiers is my profession. Those strips of no-man's land between the checkpoints always seem such zones of promise, rich with the possibilities of new lives, new scents and affections. At the same time they set off a reflex of unease chat I have never been able to repress. As the customs officials rummage through my suitcases I sense them trying to unpack my mind and reveal a contraband of forbidden dreams and memories. And even then there are the special pleasures of being exposed, which may well have made me a professional tourist. I earn my living as a travel writer, but I accept that this is little more than a masquerade. My real luggage is rarely locked, its catches eager to be sprung.

Gibraltar was no exception, though this time there was a real basis for my feelings of guilt. I had arrived on the morning flight from Heathrow, making my first landing on the military runway that served this last outpost of the British Empire. I had always avoided Gibraltar, with its vague air of a provincial England left out too long in the sun. But my reporter's ears and eyes soon took over, and for an hour I explored the narrow streets with their quaint tea-rooms, camera shops and policemen disguised as London bobbies.

Gilbratar, like the Costa del Sol, was off my beat. I prefer the long-haul flights to Jakarta and Papeete, those hours of club-class air-time that still give me the sense of having a real destination, the great undying illusion of air travel. In fact we sit in a small cinema, watching films as blurred as our hopes of discovering somewhere new. We arrive at an airport identical to the one we left, with the same car-rental agencies and hotel rooms with their adult movie channels and deodorized bathrooms, side-chapels of that lay religion, mass tourism. There are the same bored bar-girls waiting in the restaurant vestibules who later giggle as they play solitaire with our credit cards, tolerant eyes exploring those Unes of fatigue in our faces that have nothing to do with age or tiredness.

Gibraltar, though, soon surprised me. The sometime garrison post and naval base was a frontier town, a Macao or Juarez that had decided to make the most of the late twentieth century. At first sight it resembled a seaside resort transported from a stony bay in Cornwall and erected beside the gatepost of the Mediterranean, but its real business clearly had nothing to do with peace, order and the regulation of Her Majesty's waves.

Like any frontier town Gibraltar 's main activity, I suspected, was smuggling. As I counted the stores crammed with cut-price video-recorders, and scanned the nameplates of the fringe banks that gleamed in the darkened doorways, I guessed that the economy and civic pride of this geo-political relic were devoted to rooking the Spanish state, to money-laundering and the smuggling of untaxed perfumes and pharmaceuticals.

The Rock was far larger than I expected, sticking up like a thumb, the local sign of the cuckold, in the face of Spain. The raunchy bars had a potent charm, like the speedboats in the harbour, their powerful engines cooling after the latest highspeed run from Morocco. As they rode at anchor I thought of my brother Frank and the family crisis that had brought me to Spain. If the magistrates in Marbella failed to acquit Frank, but released him on bail, one of these sea-skimming craft might rescue him from the medieval constraints of the Spanish legal system.