Contents

1

Giant of History

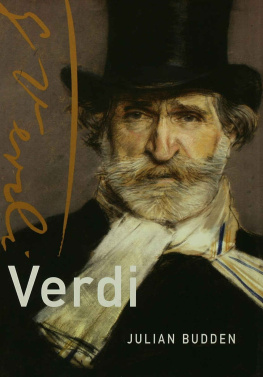

I was taken to my first opera by my father. It was a week or so before my ninth birthday and the opera was Verdis Rigoletto, a rip-roaring work about sex and murder, two topics I did not yet know much about! However, I was perfectly capable of recognising big, bold passions as they came pouring across the footlights and, to this day, well over two-thirds of a century later, I still recall the overwhelming impact of my first exposure to this most ambitious and multimedia of art forms. The extravagant sets and colourful costumes, the big theatrical gestures and passionately projected voices, and above all Verdis energised, dynamic music with its muscular mix of bravado and pathos, ecstasy and anger, tears and ultimate tragedy: I devoured them all. During the first interval, my father turned to me, gently asking whether I had had enough and would I like him to take me home? No, I exclaimed with mock resentment, I do not want to be taken home, adding: We havent even got to the bit that I know from your gramophone records: La donna mobile! That night, I laughed with the lascivious duke, loved with the vulnerable Gilda and wept at the end with her bitter, bereaved father. Today, well over a thousand opera performances later, I still find myself deeply moved by a great performance of a great opera such as Rigoletto.

Opera is the art form which, historically, emerged from the attempt in late Renaissance Italy to combine and integrate all the others. Most of the operas produced in the centuries since have fallen by the wayside with only a tiny number forty or fifty perhaps from among the many thousands that have been written consistently retaining a place in the worldwide repertoire. Operas by Meyerbeer, once popular, are nowadays rarely performed, while some by Handel, long disregarded as unperformable on stage, have recently enjoyed an unaccustomed place in the operatic sun. A handful of composers (Bizet, Gounod, Mascagni, Leoncavallo) cling to operatic immortality primarily because of a single work that has managed to retain its popularity. But who can be said to have contributed a number of works to the universally accepted operatic repertoire? Mozart and Puccini certainly; Rossini, Donizetti and Richard Strauss probably. And then come the giants, Wagner and Verdi. Of this select band, probably the most widely performed, from his day to ours, is Giuseppe Verdi. My father was right to take me to Rigoletto, an opera that remains a mainstay of every self-respecting company in the world and has done so consistently ever since its 1851 premiere. Much the same is true of La traviata or works such as Il trovatore and Aida. Ambitious Verdi operas such as Don Carlos, Un ballo in maschera, La forza del destino and Simon Boccanegra, all of them packed with poignant, lyrical beauty punctuated by big-scene grandeur, continue to receive new productions in the opera houses of the world, while Verdis final works for the stage, Otello and Falstaff, two masterpieces with nothing in common except their Shakespearean inspiration, each provide a supremely powerful theatrical experience when produced with a cast capable of doing them justice.

But Verdi is not just a giant of operatic history or a massively creative artist. He also grew to become a giant figure in the history of his nation. When Italy achieved unity and statehood for the first time in 1861, Verdi was invited to become a deputy in the first all-Italian parliament and later made a senator for life. On his death in 1901, the old man was universally mourned as the supreme embodiment of the nation he had helped create, a beloved national treasure comparable with that other crusty octogenarian, Queen Victoria, who had passed away a few days before. A month later, as vast crowds poured into the streets of Milan to witness his progress to his final resting place, many people throughout Italy felt that Verdis importance to his country was as potent as his importance to his art.

***

Verdi died in the Gran Hotel et de Milan, just up the road from La Scala, on 27 January 1901. During his final decline, the city authorities covered the streets outside his hotel room with straw to dull the sound of horses hooves, and people began to congregate nearby as their beloved maestro sank gradually towards his inevitable demise. On the day of the funeral, as the cortege wound its way across Milan, the largest crowds the city had ever witnessed lined the route. Gently and spontaneously, they began to sing the chorus Va pensiero (from his opera Nabucco), Verdis paean to his beloved homeland penned nearly sixty years earlier as a coded anthem yearning for a united, independent Italy.

Thus the legend. And, like most legends, or clichs, it contains an element of truth. In fact, Verdis actual funeral was, as he had instructed, a relatively modest affair and he was initially buried in Milans Cimitero Monumentale. But a month later, to great pomp and circumstance, his body was transferred to lie (alongside that of his wife) across town in the crypt of the Casa di Riposo, the home for retired musicians that Verdi himself had founded and funded. As the cortege was about to leave the Cimitero, Arturo Toscanini, the 33-year-old principal conductor at La Scala, led a huge choir in a performance of Va pensiero. Some of those within earshot doubtless sang along, though press reports suggest the overall impact was diluted by the vast open-air space the choir had to fill and the prolonged whistle of a locomotive at the nearby train station. As for the suggestion that this chorus was a surrogate national hymn this may have been a common perception by 1901, but was hardly that back in 1842 when it was composed.

Much that happened in Verdis life remains clouded by myth or uncertainty, and the man himself, like many ageing celebrities, was not above adding to the mystique. I am just a peasant, rough-hewn, Just a peasant? No. But one can see why the wealthy celebrity of the 1870s and 1880s, feted in cities like Milan and Paris, might have said so when reminiscing about the remote flatlands of his early childhood.

The Verdi mythology starts with the date of his birth and the home in which he was raised. For over sixty years the composer told people that he was born in Le Roncole (the scythes), a little village in the Po Valley near Busseto in the Duchy of Parma, some 65km or so south-east of Milan, on 9 October 1814. That is what his mother Luigia had told him. In fact, as his birth certificate attests, he had been born a year earlier, in October 1813 but (according to the ecclesiastical record in the local church as well as the civic record) more likely on 10 October. He was certainly born in Roncole, but not in the house with the slanting roof which, to this day, remains the official birthplace of the great man. The family did live there, but not until the boy was in his early teens. And his baptismal name was not Giuseppe but Joseph; in 1813 the region was still under French rule and it was another couple of years before the baby could become Giuseppe in the eyes of officialdom.

Meanwhile, another somewhat mythologised event occurred. In 1814, the anti-Napoleon troops of the so-called Holy Alliance pushed their rough way across parts of northern Italy, including the Parma region. Many years later, the composer told a visitor how, when a contingent of Russian soldiers (perhaps Cossacks) came to occupy Roncole, their outrages brought grief and terror to its citizens.

We must not read too much into the semi-truths embodied in these stories and others we will encounter later. Family records were invariably patchy in small-town Italy during the nineteenth century, and Verdi is probably no different from many of his contemporaries in giving credence to a series of questionable anecdotes passed down from one generation to the next. But two things are worth noting. First, because of the international stature Verdi went on to achieve, many of these myths soon found their way into what, until modified by recent research, was for long the universally accepted narrative of his life. Second, it becomes clear as one reads the detailed record that Verdi himself seems to have, I hesitate to say lied, but at least to have embellished, perhaps subconsciously, certain aspects of his personal history.