At Thames & Hudson I am grateful, as before, to Jamie Camplin, and to Helen Farr, Amanda Vinnicombe, Johanna Neurath, Karin Fremer, Avni Patel and Sam Wythe, as well as to Imogen Graham, who located and rounded up the illustrations. At United Agents, my thanks to Caroline Dawnay. It is a pleasure to acknowledge the help of two friends from earlier days in Oxford: Gregory Dowling photographed the busts in the Venetian garden where the idea of this book first occurred to me; and the manuscript was edited with ferocious exactitude by Richard Mason, whose own love for and knowledge of the subject made our work together a true collaboration.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Peter Conrad taught English literature at Christ Church, Oxford, from 1973 to 2011. One of the great cultural critics of our time, he has written books on a wide range of subjects, including Modern Times, Modern Places; A Song of Love and Death: The Meaning of Opera; and Creation: Artists, Gods and Origins.

Also by Peter Conrad:

Modern Times, Modern Places: Life and Art in the 20th Century

Creation: Artists, Gods & Origins

Islands: A trip through time and space

At Home in Australia

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagners Life and Music

Richard Wagner: The Sorcerer of Bayreuth

Wagners Ring of The Nibelung

Opera: A Concise History

The Chronicle of Opera: Year-by-year Four Centuries of Music, Performance and Recording

The Chronicle of Classical Music: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and Music of the Great Composers

Mozart: The Golden Years 1781-1791

Mahler: His Life, Work and World

Haydns Visits to England

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Originally published in the United Kingdom in 2011 as

Verdi and/or Wagner: Two Men, Two Worlds, Two Centuries

ISBN 978-0-500-51593-8

by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

and in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

Copyright 2011 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

This electronic version first published in 2013 by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

First published in 2013 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

To find out about all our publications, please visit

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-500-77135-8

ISBN for USA only 978-0-500-77144-0

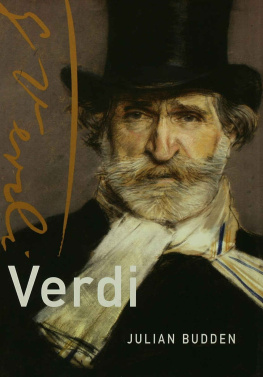

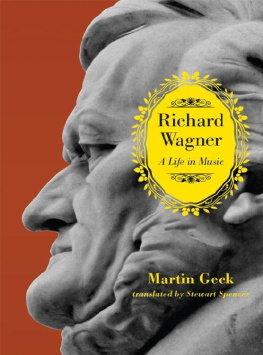

On the cover: (left) portrait of Verdi, woodcut after a photograph, 1893; (right) portrait of Wagner, engraving by Veit Froer, 1883, after a photograph of c. 1871. (akg-images)

This is surely as close as they ever got to each other: they stand, with a buffer zone of lawn between them, in a garden at the edge of Venice beyond the Arsenal, where the floating city begins to trail off into the lagoon. Despite their proximity, each pretends to be alone. A path relegates them to separate patches of grass; one of them hides in the shrubbery, while the other, asserting his right of occupancy, stands on a slope and stares across the water. Their memorials are modest enough, since they are not the kind of men who rear on bronze horses or balance atop columns like conquerors. Reduced to heads, they are set on pedestals that state their names. The one who skulks in the bushes is Giuseppe Verdi. The other his jaw set at a confrontational angle like a mountain ledge as he scans the horizon for detractors, or perhaps for devotees on pilgrimage to his shrine is Richard Wagner.

So comparable but so incompatible, they were born in the same year Wagner on 22 May 1813 in Leipzig, Verdi on 10 October 1813 in Le Roncole near Busseto in the Duchy of Parma. For official purposes Wagners father was a clerk in the police service, although Richard may have been the son of a Jewish actor called Ludwig Geyer whom his mother, widowed when the boy was six months old, soon married. Verdis background was less shadowy, though not quite as humble as he liked to claim when calling himself a rough-hewn peasant: his father kept an inn that doubled as a village grocery.

As their busts testify, Verdi and Wagner were both cultural heroes, but of different kinds a native son attached to the soil versus a wandering exile; a tribune of the people versus a dictatorial aesthete; a man of progress versus an atavistic myth-maker; a spokesman for afflicted humanity versus a creator of gods, giants, dragons, dwarfs and fairies. Like saviours, both composers appeared as if in answer to a prayer. When Verdis first opera, Oberto, was performed at La Scala in November 1839, a critic remarked that the audiences grateful, almost worshipful reaction meant We have a Messiah. A less enthusiastic reviewer in Leipzig in 1845 complained that Wagner was being touted as the Messiah of opera. By the end of their lives they had turned into incarnations of their times, the Zeitgeist made flesh. All of Italy grieved when Verdi died on 27 January 1901, and the government decreed a period of mourning longer than that awarded to a monarch. The Italian parliament devoted a session to eulogizing him, during which one of the deputies justly claimed that Verdi was more than a man of the nineteenth century: he personified the century, which lived in and through him. Wagner, however, did not wait for others to promote him posthumously to the role of legislator for the age. He knew, he said, that his purpose was to tell the century all that we have to say to it!

Despite their affinities, Verdi and Wagner spent the best part of the nineteenth century managing not to meet, and since the early twentieth century they have stood in the Venetian garden at a diplomatic distance, not quite turning their backs on each other but also stubbornly declining to reach an accord. The differences were personal, and the busts, for all their second-hand crudity, hint at that. In his shelter of leaves, Verdi craves anonymity: he despised publicity, shunned high society, and prematurely retreated from the cities where his operas were performed to live like a farmer on his estate at SantAgata near Busseto. Across the way, Wagner on his small eminence confronts the world rather than withdrawing from it. He is a candidate for a heros life, prepared for struggle and intent on prevailing, proud of his isolation. The planes of Wagners clean-shaven face were already sculptural before anyone attempted to carve them in marble, but Verdi is less sleek and smooth, and his bust gives him the fringe of beard he always wore another defence, like the encroaching leaves of his impromptu bower, against being seen and evaluated. Wagner has no arms: the brain in that armoured skull can apparently dispense with appendages. Verdi, however, is allowed the use of his right arm, which grips a roll of music paper against his chest. His hand makes a stout, dependable gesture of faith, like an American pledging allegiance to shared verities. One man is portrayed as a frowning mind, the other as a more sensitive being who translates emotions into song as if the hearts affections had been directly transmitted in crotchets and quavers that stand for spasms and palpitations to the page he holds.

The pedestal that props up Wagners self-sufficient head has a squashier interior, a metaphorical recess of punctured flesh and spilt blood. On the plinth, a pelicans scissory beak rends its breast to feed its jostling offspring, which pick at the exposed entrails. Ezra Pound, walking in the gardens near the end of his life, was asked by his minder what the low-relief medallion meant. Toujours les tripes, he said: a vile daily diet of offal. In fact the self-rending bird is a religious icon, traditionally an emblem of Christs sacrifice for the sake of fallen mankind. Profanely reinterpreted here, it suggests the source on which Wagner drew for his last opera: Was ist die Wunde asks the stricken Amfortas in

Next page