Martin Geck is professor of musicology at the Technical University of Dortmund, Germany. His other books include Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work and Robert Schumann: The Life and Work of a Romantic Composer.

Stewart Spencer is is an independent scholar and the translator of more than three dozen books.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2013 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2013.

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92461-8 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92462-5 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226924625.001.0001

Originally published as Wagner: Biografie. 2012 by Siedler Verlag, a division of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH, Munich, Germany.

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International, translation funding for humanities and social sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT, and the Brsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers and Booksellers Association).

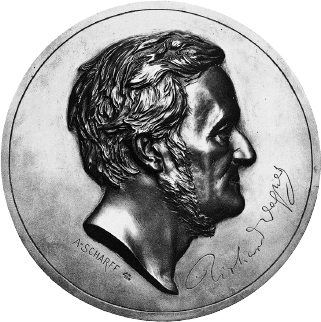

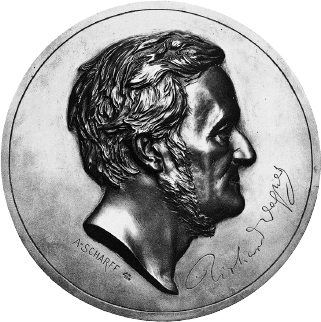

: Bronze medallion by Anton Scharff (18451903) of Vienna. Wagner sat for him at Schloss Fantaisie near Bayreuth in June 1872 in the wake of the official ceremony accompanying the laying of the foundation stone of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus on May 22, 1872. (Photograph courtesy of the author.)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Geck, Martin.

[Wagner. English]

Richard Wagner : a life in music / Martin Geck ; translated by Stewart Spencer.

pages cm

Translation of: Geck, Martin. Wagner. Mnchen : Siedler, 2012.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-92461-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-92462-5 (e-book) 1. Wagner, Richard, 18131883. 2. ComposersGermanyBiography. I. Spencer, Stewart, translator.

II. Title.

ML410.W1G2913 2013

782.1092dc23

[B]

2013014426

Additional figure credits: Portrait of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, , photograph courtesy AKG-Images.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

RICHARD WAGNER

A Life in Music

MARTIN GECK

Translated by

Stewart Spencer

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

CONTENTS

FIGURING OUT WAGNER?

Cosima Wagners diaries run to nearly one million wordsover 2,500 pages in the two-volume German edition and only slightly less in Geoffrey Skeltons English-language translation. The first entry is dated January 1, 1869, the last one February 12, 1883. Barely a day is omitted. Moreover, Wagner himselfand it is around him that these entries revolvekept a close eye on his wifes record of their lives together, a point confirmed by entries in his own hand. At first sight, then, the final fifth of Wagners life seems to be seamlessly documented, so much so, indeed, that it appears to require little effort to figure out who Wagner was.

But what does the term document mean in such a context? Of course, these diaries include many undisputed facts. And yet how many of the incidents related here are given a tendentious gloss? And how many are simply suppressed? The main problem is that Cosima dedicated her diaries to her children: You shall know every hour of my life, so that one day you will come to see me as I am. But she was writing these lines at the very time that she and her two illegitimate daughters by Wagner (Isolde and Eva), were fleeing from a loveless marriage with Hans von Blow and moving to Tribschen on Lake Lucerne in order for her to live with him in what was pilloried at the time as sin.

Her daughters were too young to be able to make any sense of this information. But her diary was in any case never designed to leave any trace of the intimate affair between its author, Cosima von Blow, and its subject, Richard Wagner. As a result, their eldest daughter Isolde, affectionately known as Loldi, is passed off as the daughter of Hans von Blow. Even as late as 1914, when Isoldeprompted by her husband, who was anxious to advance his claim to his Wagnerian inheritancetook her mother to court in an attempt to prove who her father was, Cosima won the case on a technicality but was forced to admit under oath that she had slept with Wagner at the time of the childs conception. In the wake of this public revelation, Isoldes name could never again be mentioned in Cosimas presence. Yet how can we square even this one tiny detail with the line from Cosimas diary, You shall know every hour of my life?

But are not the many thousands of comments that Wagner himself made between 1869 and 1883 about his life and works, about art, politics, and religion, about the Jewish question and about vivisectioneverything, in short, about God and the worlda veritable mine of information? Not only are they a mine, they are also a minefield. After all, these remarksat least to the extent that they were made within the family circleare known to us almost entirely through Cosimas record of them. It appears that she made these entries in her diary at irregular intervals, often days apart, relying on the notes that she jotted down in the meantime. But how reliable was this method? And which remarks did she record without any explanation? Which did she suppress? And which did she alter in keeping with her own interpretation of them?

As we have seen, Richard Wagner read her jottings, at least from time to time, but not once did he make any attempt to correct them. And yet this does not mean that he never felt that Cosima had misunderstood him throughout these final fourteen years of his lifeto assume otherwise would fly in the face of reason. Rather, he evidently had no desire to meddle in his wifes affairs but preferred on this point at least to leave her to her own devices. We do not need to interpret this, as many of Cosimas biographers have done, as an instance of her iron rule: marital relations can rarely be reduced to such simplistic terms. But we would certainly not be wrong to speak of Cosima and her husband inhabiting parallel worlds. And these two worlds cannot be aligned simply by our arguing that Cosima regarded herself as Wagners mouthpiece.

Can we expect a greater degree of authenticity from the new critical edition of Wagners nine thousand or so surviving letters, an edition that now runs to twenty-two volumes and has reached the year 1870? And what about the truth of Wagners autobiography, My Life, in which the composer devotes some eight hundred pages to an account of the first four-fifths of his life, leaving a gap of only four years before Cosimas diaries take over? The mere fact that Wagner dictated his memoirs to Cosima and intended them to be read above all by King Ludwig II suggests that his interpretation of the truth was occasionally fast and loose. This does not mean that we must necessarily accuse Wagner of wanting to present an unduly flattering picture of himself. If we ignore simple gaps and genuine lapses of memory, then his conscious or unconscious desire to surround himself and the creative process with an aura of mystery will have played a greater role here.

Here, too, there are various traps lying in wait to catch the unwary biographer. Even such an intelligent writer as Martin Gregor-Dellin, whose contribution to Wagnerian literature cannot be dismissed out of hand, is repeatedly guilty of falling under the narcotic spell of Wagners life and works and, like Isolde, sinking and drowning in this sea of self-mystification. While on the one hand claiming to maintain a certain skepticism toward Wagners own account of his life, there are times when Gregor-Dellin identifies so intensely with his subject that he gives the impression that he actually witnessed the events he is describing. And where Wagner and Cosima remain monosyllabic, Gregor-Dellin becomes positively voyeuristic: As for Wagner, he succumbed to the lure of her shapely breasts, drew her to him and smothered her with passionate kisses. Thus Gregor-Dellin describes Wagners late infatuation for Judith Gautier, a relationship that remains, at best, a matter for speculation.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).