Contents

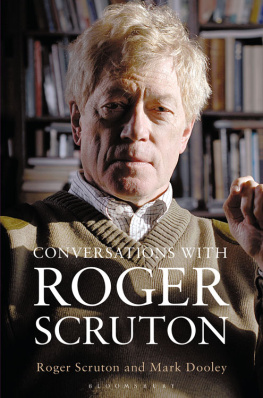

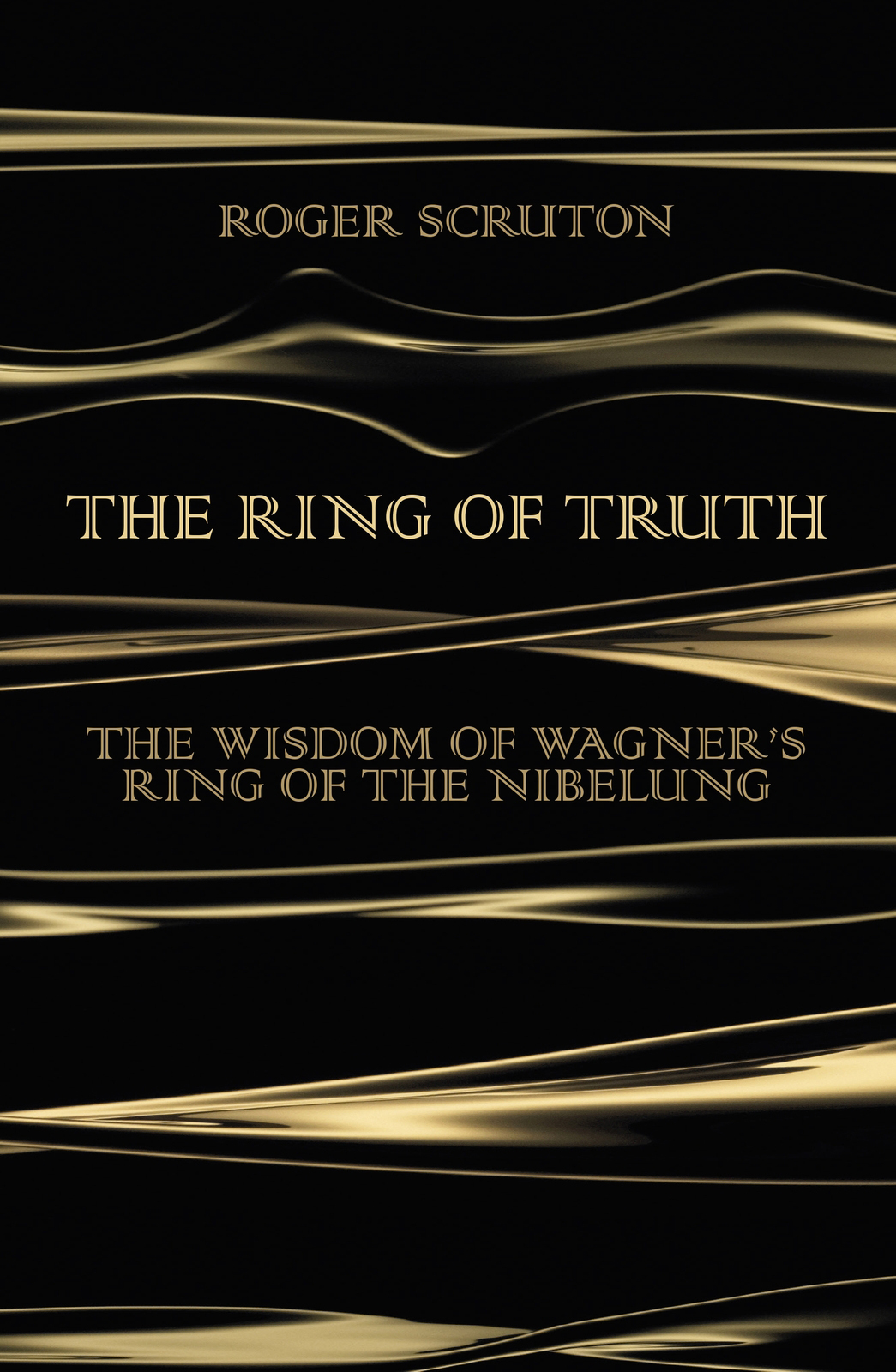

Roger Scruton

THE RING OF TRUTH

The Wisdom of Wagners

Ring of the Nibelung

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2016

Copyright Roger Scruton, 2016

Cover photograph Jonathan Knowles/Getty Images

Cover design: Antonio Agnelo Colao

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-241-18856-9

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

Preface

This is a work of criticism and also of philosophy. I try to explain Wagners artistic achievement in his tetralogy of The Ring of the Nibelung, and also to use the work as a vehicle for philosophical reflection. I emphasize throughout that the meaning of The Ring cannot be understood without appreciating the music. That said, I have kept technical analysis to a minimum, confined detailed description of the music to one chapter (.

The book began life as a series of three lectures delivered in 2005 in Princeton, under the auspices of the Council for the Humanities. Sarah-Jane Leslie attended those lectures and vigorously contested my interpretation of the cycle. I am very grateful to her for her combative encouragement over the years, and for persuading me to take the character of Brnnhilde far more seriously than I was then inclined. I owe a debt of thanks to Paul Heise, whose extraordinary dedication to Wagners masterpiece has been an inspiration to my work, and whose comments on an earlier version have greatly clarified the argument. I am also indebted to Andreas Dorschel, who put me right on many points both scholarly and philosophical.

I have learned much from the keen and constructive criticism offered by Philip Kitcher and Robin Holloway, and have depended from the beginning on the generous encouragement and insight of two friends, Jonathan Gaisman and Robert Grant, without whose broad knowledge and musical culture I would have been many times led astray. Finally I owe a special thanks to my publisher, Stuart Proffitt, whose attentive criticism of earlier drafts has led to radical changes for the better.

Scrutopia, 2015

1

Introduction:

The Work and the Man

He provided the story and the characters that would, in their Nazi caricature, become the icons of German racism. He scandalously mistreated those who subsidized his extravagant life, including his erratically devoted sovereign, King Ludwig II of Bavaria. He had a penchant for the wives of other men, and in his most notorious tribute to forbidden sexual relations, portrayed incest in terms that were both sympathetic and the raw material for subsequent racist fantasies.

Nor did his mistakes end with his death. Not only did he become Hitlers favourite composer, but the Nazi caricature of the Jew was read back into Wagners villains. Alberich, Mime and Klingsor were regularly presented on the German stage as though imagined by Dr Goebbels, and his theatre at Bayreuth was used to turn Wagner into the founder and high priest of a new and sinister religion. As a result of these mistakes, only some of which are strictly attributable to Wagner, the tendency has arisen to treat the composers works as expressions of his personality, to analyse them as exhibits in a medical case study, and to create the impression that we can best understand them not for what they say but for what they reveal about their creator.

The tendency is already present in the polemics with which Nietzsche tried to break from the enchanter who had cast such a spell on him (The Case of Wagner, 1888, and Nietzsche Contra Wagner, 1895). But it gathered strength in the early years of the twentieth century, when the habit arose of treating works of art as journeys into the inner life of their creator. From the first days of psychoanalysis, Wagners works were singled out as both confirming and demanding a psychoanalytic reading. Their super-saturated longing, their cry for redemption through sexual love, their exaltation of Woman as the vehicle of purity and sacrifice all these features have naturally suggested, to the psychoanalytical mind, incestuous childhood fantasies, involving a fixation on the mother as wife. Such is the interpretation maintained by Max Graf and Otto Rank, both writing in 1911. Thereafter the habit of reading the works in terms of the life became firmly established in the literature, not only among Wagners detractors, but also among his admirers, as we find in Paul Bekkers sympathetic study of 1924, Wagner: Das Leben im Werke.

Later, writing in reaction to the Nazi cult of Wagner, and using the heavy machinery of Frankfurt-school Marxism, Theodor Adorno attacked the composer as a symbol of all that was hateful in the culture of nineteenth-century Germany, a purveyor of phantasmagoria whose aim and effect are to falsify reality. More recently Robert Gutman, in his comprehensive study of 1968, Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind and His Music, presented Wagner as a proto-Nazi and a characterless ogre. The accusation was rubbed in obsessively by Marc A. Wiener in his book of 1995, Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination. And the habit of psychoanalysing the composer through his works has continued. The most influential recent examples of this Jean-Jacques Nattiezs Wagner Androgyne and Joachim Khlers Richard Wagner: Last of the Titans see anti-semitism as the meaning and Oedipal confusion as the cause of just something needs to be added to the case for the defence, if we are to treat Wagners works for what they are, rather than for what they reveal, or are thought to reveal, about their creator.

Wagner himself wrote a striking autobiography. It tells the story of a fraught and difficult life and abounds in expressions of love and gratitude, as well as self-praise. The book reinvents its author as a symbol of the emerging Germany, is catty and mendacious about Meyerbeer, and is less than generous to Mendelssohn. But it steers clear of ardent nationalist and anti-semitic sentiments. Written at the request of King Ludwig II and dictated to Wagners second wife Cosima, it was issued in a small edition to be circulated among Wagners friends. But it is now regularly mined for the hidden flaws in the composers character, and for the proof however fleeting and arcane that in this or that respect he was just as ordinary as the rest of us, even though the mind revealed in the book is one of the most extraordinary and comprehensive that has ever existed. Its failure to protect Wagners reputation, either from false friends or from implacable enemies, is reflected in modern productions of Wagners one attempt to portray the day-to-day life of the German people: