About the Author:

Born in Australia, Peter Conrad taught English literature at Christ Church, Oxford, from 1973 to 2011. He is a regular contributor to The Observer, and has written more than twenty books, including The Hitchcock Murders; Orson Welles: The Stories of His Life; How the World Was Won: The Americanization of Everywhere; Modern Times, Modern Places; and At Home in Australia.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Verdi and/or Wagner: Two Men, Two Worlds, Two Centuries

Peter Conrad

Mythomania: Tales of Our Times, From Apple to Isis

Peter Conrad

Tarkovsky: Films, Stills, Polaroids & Writings

Andrei A. Tarkovsky, Hans-Joachim Schlegel and Lothar Schirmer

Cinema: The Whole Story

Christopher Frayling

Be the first to know about our new releases, exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

CONTENTS

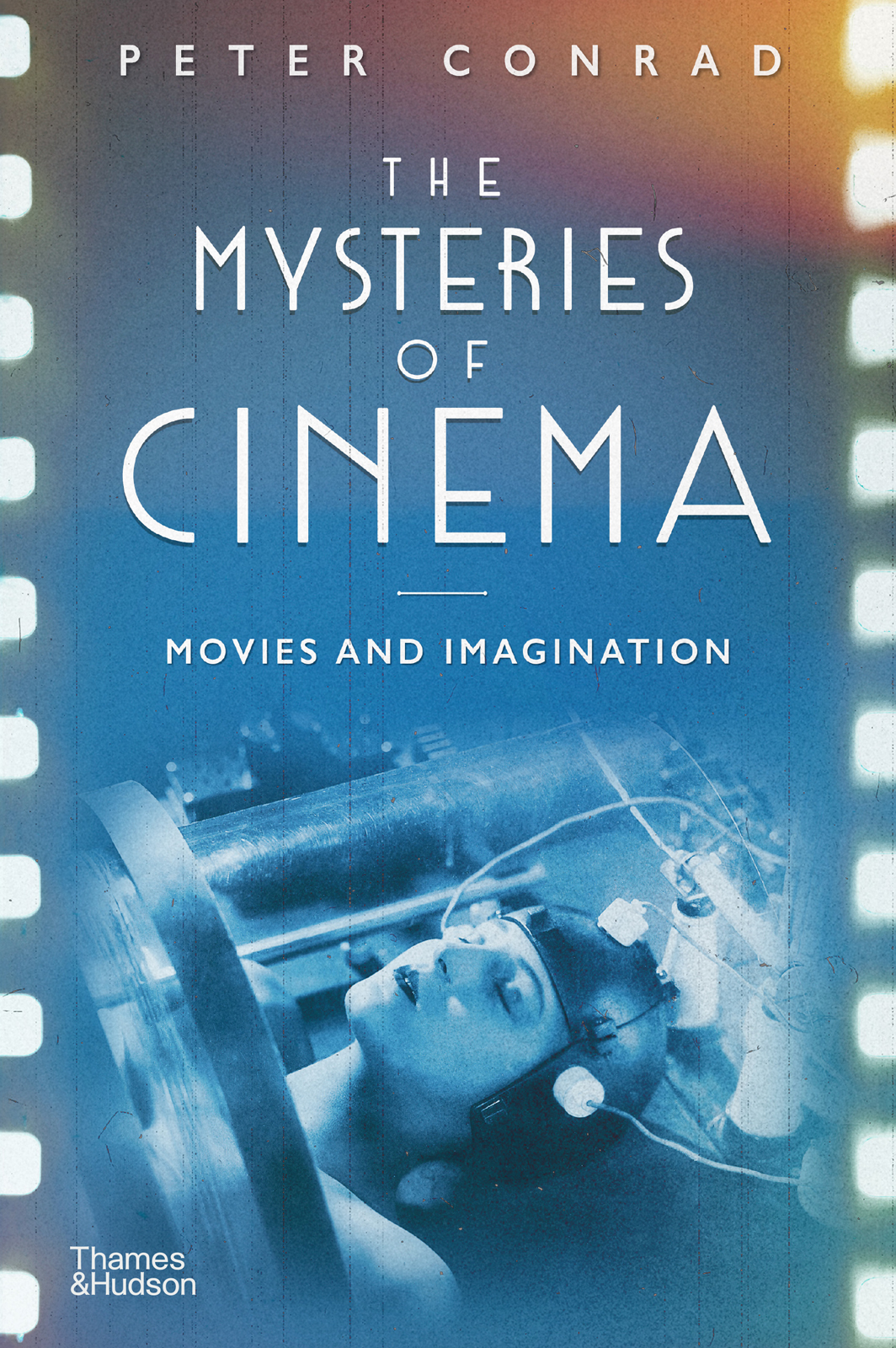

At the end of the nineteenth century, an eerie marvel startled the world. A product of science, it challenged religion: thanks to a machine that could do the work of a god, light materialized in darkness and made images move. But the films! exclaimed Leo Tolstoy in 1908. They are wonderful! They had, the nonagenarian novelist declared, divined the mystery of motion, and he excitedly mimicked the insect-like buzz of the contraption that performed this feat: Drr! Drr!

The shock of animation recaptured the moment in Genesis when clay was first imbued with life. Better yet, these moving pictures told stories without needing to rely on words, so the new art earned extra praise for overcoming the curse of Babel. In Genesis, when the earth was of one language, men built a sky-scraping tower that reached up towards heaven. A jealous God toppled the structure and, to ensure that his creatures could never again undertake such a grandiose collective work, confounded their speech. According to the myth, this was how monoglot mankind splintered into linguistic tribes whose members babbled at each other without being able to communicate. Cinema, which bypassed language altogether in its silent days, restored a universality that we supposedly lost when the tower fell.

In 1918, in an essay rejoicing in the advent of cinema, the surrealist poet Louis Aragon said that he was happy to be deprived of everything verbal: so much for the humanist definition of Homo sapiens as an animal uniquely endowed with the power of speech. Language had enabled us to argue, to tell lies. Cinema, by contrast, possessed an ecumenically sympathetic reach. Because Charlie Chaplins battered but eternally resilient tramp never spoke, viewers everywhere could laugh at his physical pranks or shed tears over his emotional distress. As cinemas first global celebrity, he made the whole world kin.

George Bernard Shaw took stock of an epochal change in 1914 when he welcomed cinema as a much more momentous invention than the printing press. Shaw admired Chaplin, but thought that the possibilities of dramatic dumb show and athletic stunting would soon be exhausted; instead he expected cinema to begin educating people as soon as the projection lantern begins clicking. He hoped that these silent lectures delivered in what he called electric theatres would contribute to the sum of our shared knowledge, spreading news, demonstrating natural history and biology and so on. Cinemas true mission turned out to be less worthily literate: its gift to us is not information but empathy. Shaws own drama upheld the primacy of talk, and in 1919 he forbade a cinematic adaptation of Pygmalion. How, he demanded, can you film Not bloody likely? But he was wrong to think that The silent drama is exhausting the resources of silence, as he claimed in 1924. Words can only approximate to the ideas or emotions they seek to translate, whereas the cameras first close-ups, studying the face as a living organism not a pictorial mask, suggested that it might be possible to film thought.

The new art looked at the world in new ways, and endowed human beings with sensory capacities and mental powers unknown before; this book sets out to explore the altered, heightened state of awareness that films induce, and to show how it has permanently changed our understanding of life. In 1929 the critic Andr Levinson boldly declared that cinema was responsible for the greatest philosophical surprise since the eighteenth century, when Immanuel Kant demonstrated that time and space were subjectively perceived, not entities in themselves. Cinema, Levinson implied, went further: it made Kant redundant because it merged two categories of experience that had always been kept apart, and as a result it was able to convey the sensation of being alive.

Vitagraph, a studio that opened in Brooklyn in 1897, came up with an apt coinage: its products exhibited vitality. The Bioscope, a travelling film show that toured fairgrounds for a decade or so after the late 1890s, used a similar etymology to advertise the living things that could be seen on its screens. The name of cinema establishes that it is a product of kinesis, devoted to the physical exhilaration of speed. Emerging among the gadgetry of the machine age, it has tirelessly invigorated us with the sight of people running or chasing each other or driving vehicles at maximum velocity. But cinema from its earliest days flouted the customary laws of physics in ways that athletes and automobiles could not. Time, no longer ticking at a steady pace, quickened or slowed down to match the speed at which film spooled through the projector, and space turned dynamic as the camera travelled through it. Reversed motion sent bodies skittering backwards, or made swimmers vault out of the water in defiance of gravity. Sitting still to watch a film, people twisted and turned through a demonstration of what Albert Einstein called relativity.

More than a technical innovation, Levinson considered cinema to be a Messiah-like cosmic agent. It addressed a new audience of multitudes whom it turned into converts, worshippers of the exotic beings they saw on screen: a fan is a fanatic the Latin word identified a temple servant, charged with tending the sacred fire. Vachel Lindsay, a proselytizing American bard who preached the gospel of cinema, said in 1915 that films were an answer to the non-sectarian prayers of the entire human race. The Italian poet and essayist Ricciotto Canudo sensed a more Manichean force at work. In 1908 he declared that cinemas clockwork mechanism placed it under the sign of Ahriman, the master, the destructive spirit who rules the world in the dualistic doctrine of Zoroaster. When seen through the camera, substance becomes shadow, and our familiar world dematerializes. As Man Ray pointed out when describing the solarized photographs he made during the 1920s, images on film are oxidised residues of living organisms luminous ashes. The same principle reduced the phantasmal gods and goddesses on the screen to will-o-the-wisps, clouds of light.

Next page